Having a job that requires complex social interactions — like mentoring and negotiating — might protect the brain from developing symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease by building up what researchers call cognitive reserves.

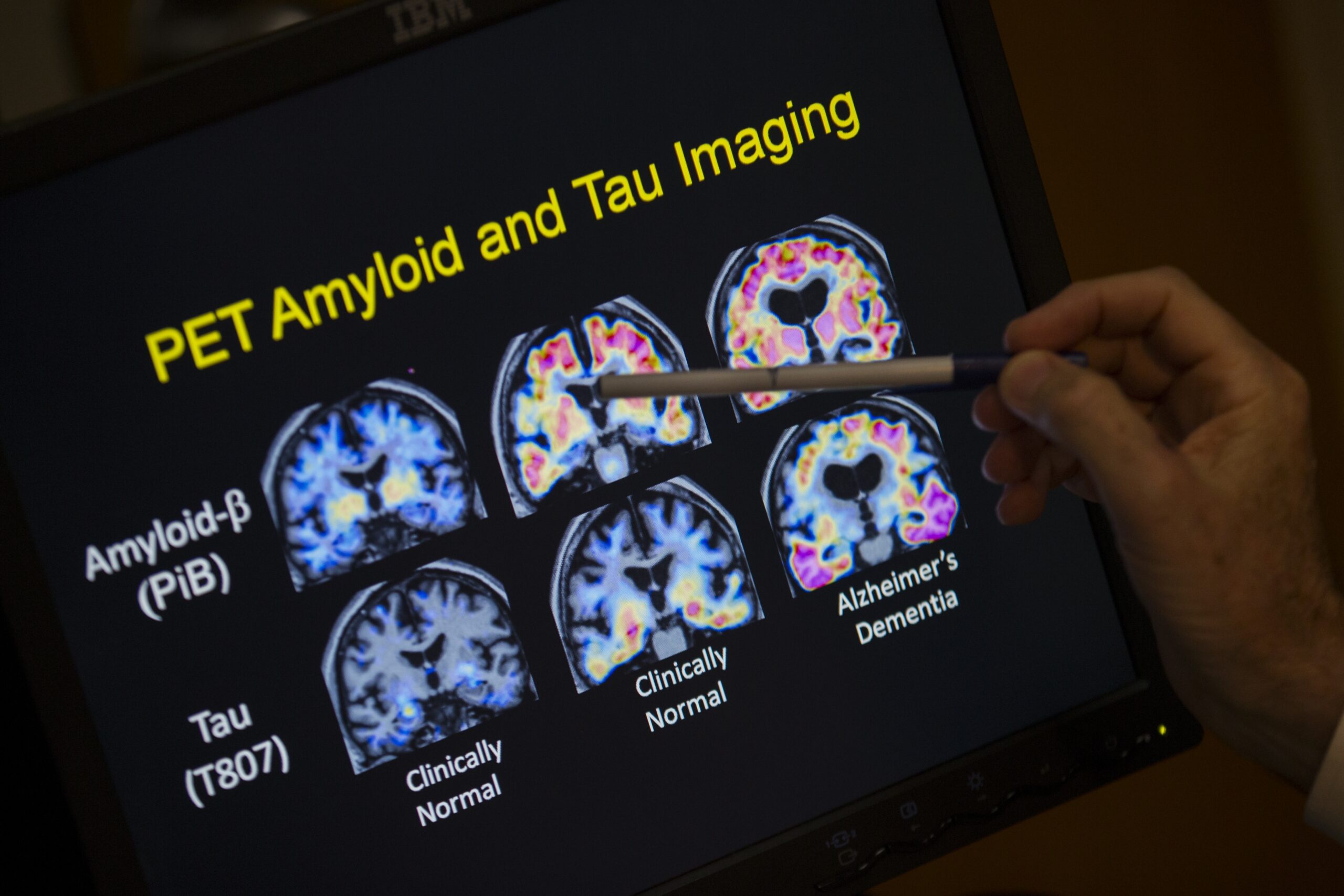

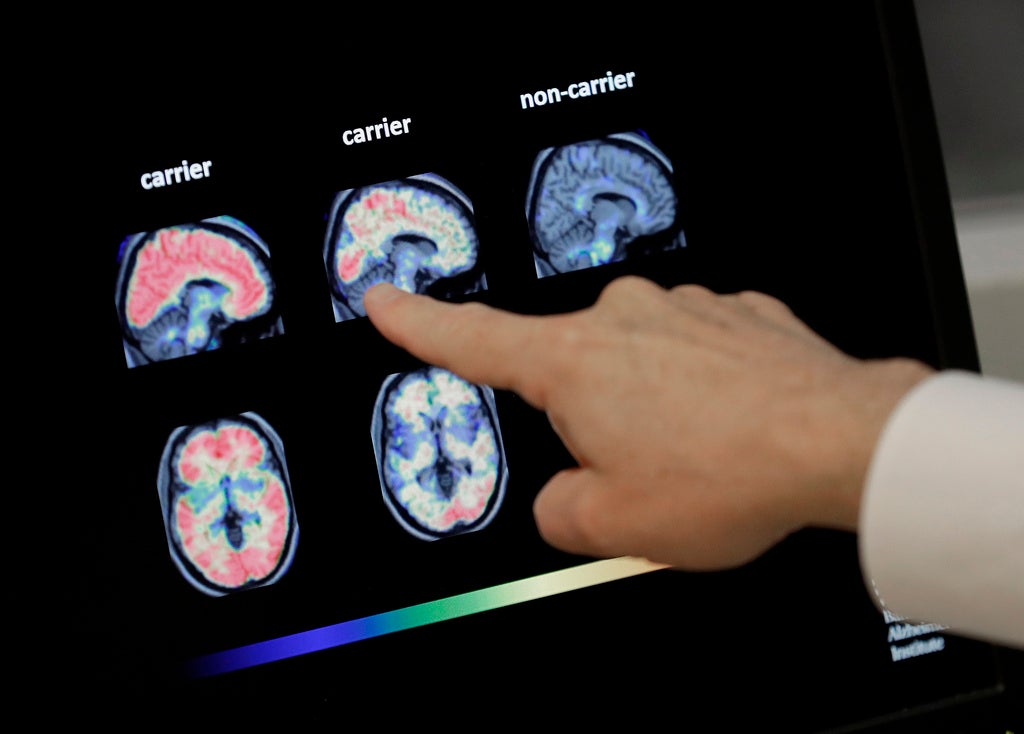

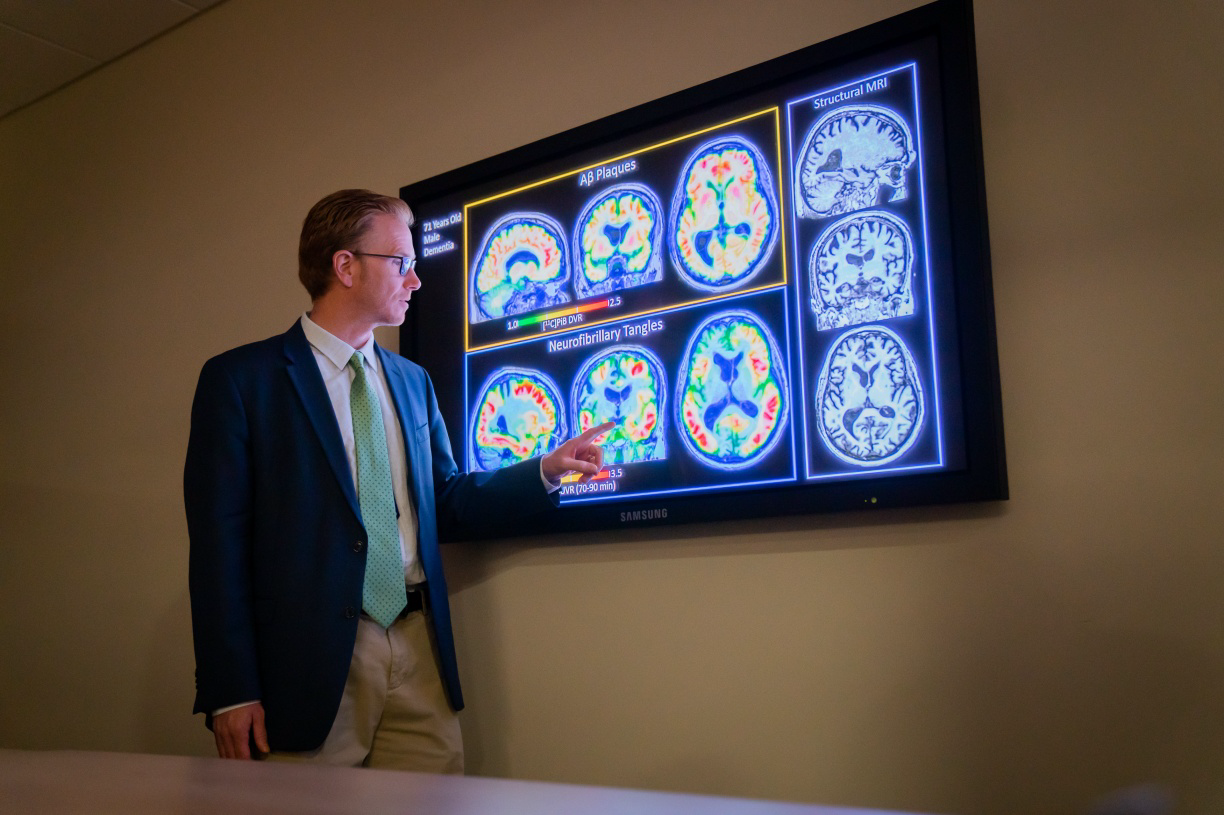

Researchers with the University of Wisconsin’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center reviewed brain scans and cognitive tests of more than 280 Wisconsinites at high risk of developing the disease who were enrolled in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention.

They found participants whose brain scans showed white matter, a marker of Alzheimer’s, were less likely to have symptoms if they held jobs involving complex social interactions.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Elizabeth Boots, a research specialist at the center and the study’s lead author, said the study builds on evidence of cognitive reserves, which other studies have shown can be built through exercise and education.

“So what that means is that for people with higher levels of occupational complexity, or higher reserves, they’re able to tolerate more white matter pathology in the brain and still perform at the same level as their peers, so it’s protective,” she said.

The study also considered job complexity related to working with things and data, but those types of complexity didn’t confer the same benefits on workers.

Dr. Ozioma C. Okonkwo leads the lab where Boots works and co-authored the study. The brain benefits of developing complex social skills can come from any area of life, he said.

“It’s not difficult to imagine that there are many opportunities for an individual to engage in mentoring even outside of the typical work day,” he said.

Their research is one of several studies focused on cognitive reserves at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in Toronto this week, Boots said.

Other studies presented this week found similar benefits from higher levels of education and brain training games that developed the ability to quickly process visual information.

These studies reinforce the idea that the brain is like a muscle, the more you use it, the stronger it gets, Ozioma said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.