Some meatpacking plants in Wisconsin have become COVID-19 hot spots, but that doesn’t necessarily mean the food they produced is unsafe, according to state health officials.

Workers at meatpacking plants around the country are coming down with the disease, leading some plants to shut down temporarily or indefinitely. President Donald Trump announced Tuesday he plans to sign an executive order to compel plants to stay open.

In Wisconsin, a spike in cases in Brown County has been linked to meatpacking plants. According to the Brown County Health Department, as of April 28, there are 255 confirmed cases among employees at JBS Packerland in Green Bay, with 79 linked cases. American Foods Group in Green Bay has 145 confirmed cases among employees, with seven linked cases.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Salm Partners in Denmark, Wisconsin, had 17 confirmed cases among workers as of April 27.

JBS Packerland has shut down temporarily due to the outbreak, and all three are under federal investigation, along with the Smithfield Foods plant in Cudahy.

A WHYsconsin question asker, John Spanjers of Menomonie, wondered if the new coronavirus can live on packaged meat or if there are other risks associated with meat packaging. He said it wasn’t a concern for him until he started seeing headlines about meatpacking workers.

“They were talking about how confined these areas are, and how close in proximity they are all to each other, and how many of them are actually getting sick with the virus,” he said, and wondered if they could be passing the illness on to consumers.

There is currently no evidence linking food or food packaging and COVID-19 transmission, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Dr. Ryan Westergaard, chief medical officer with the Bureau of Communicable Diseases at the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, said while they can’t be 100 percent sure about COVID-19, other respiratory illnesses usually do not spread through eating food.

“It’s not thought to be a great concern right now, but certainly it is always appropriate to proceed with caution,” he said.

In general, Westergaard said, respiratory illnesses prefer other paths into the body.

“What we know about coronavirus, and respiratory viruses in general, is that they cause infection by coming in contact with respiratory cells in the nose, eyes, throat and through inhaling,” Westergaard said.

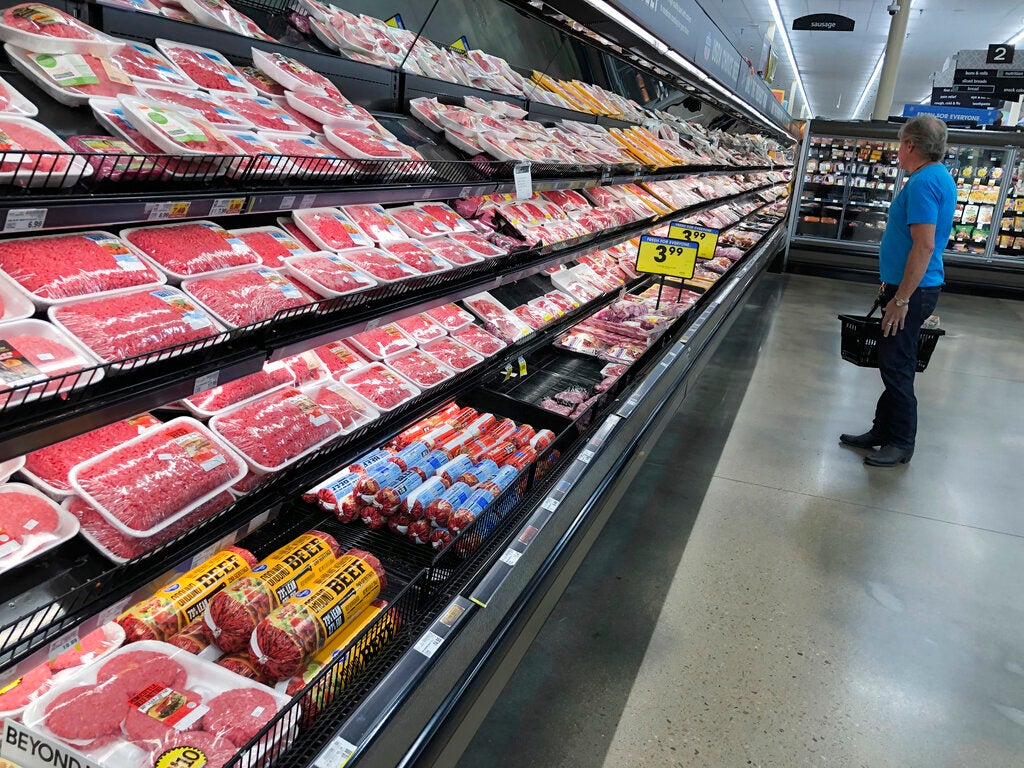

For consumers, the impact of COVID-19 cases at meat plants could have more to do with availability. Shutdowns nationwide have led to a slowdown in meat production, said Jeff Sindelar, a meat specialist and associate professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“I think that if the pandemic isn’t held at bay, if we don’t continue (to) flatten the curve, per se, it could be a real concern,” he said.

Investigative reports from The Intercept and The Washington Post found plant workers around the country who say their companies did not do enough to protect them from COVID-19.

Chicken, beef and pork producer Tyson Foods was one of them. The company took out a full-page ad in The Washington Post and the New York Times on Sunday, where board chairman John H. Tyson wrote that his plants must be allowed to operate, with safety measures like temperature checks and additional daily deep-cleans.

“In small communities around the country where we employ over 100,000 hard-working men and women, we’re being forced to shutter our doors,” Tyson wrote. “This means one thing — the food supply chain is vulnerable.”

But Sindelar said it’s not time to panic, because there’s still plenty of meat and poultry in the U.S. — even with some major plants closed.

“How much there is, and what specific cuts are, that’s probably a little more volatile right now,” Sindelar said.