In 2016, “Roberto” legally came to the United States for the same reason many immigrants do — to earn a living and a slice of the American dream. But Roberto, a native of southern Mexico, says he suffered a nightmare of coercion, financial exploitation, threats and mistreatment while working on a Georgia farm and, later, at cabbage patches in southeastern Wisconsin.

Roberto arrived in the United States legally under an H-2A visa, which allows seasonal farm laborers to work for specific employers. Roberto says he was forced to pay a fee and turn over the deed to his parents’ property to an intermediary in Mexico as security for his continued work in the United States.

When Roberto arrived in Georgia, the situation was not at all what the recruiter had described. There were hundreds of workers — all men, all from Mexico — living together in cramped barracks and isolated from nearby towns, he said.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“The same day you arrive, that same day they ask you for your passport. They take all of your personal documents,” Roberto said of the contractors, who hired out workers to farms growing squash, cucumbers and cilantro in southern Georgia.

The boss warned Roberto and the other workers that there were ground rules.

“He tells us to get it in our heads that we came to work,” Roberto recalled. “No matter what, they don’t want us talking to any strangers — people that are not from the work site. And that we couldn’t leave either — work, and then back to the house.”

Roberto — not his real name — is among 14 men from Mexico who were allegedly victimized by a labor-trafficking scheme that transported legal temporary farm workers from Georgia to work illegally at a Racine-area farm, according to an indictment in the U.S. District Court in the Eastern District of Wisconsin announced May 22.

He spoke exclusively to Wisconsin Public Radio and Wisconsin Watch in 2017, before the indictment, and has asked through his attorneys to remain anonymous to avoid potential retribution. At their request, WPR and Wisconsin Watch delayed publication of the interview to avoid compromising the investigation.

Five family members from Garcia & Sons, a farm labor contractor from Moultrie, Georgia, have been charged with labor-trafficking related counts. They are Saul Garcia, 49; Saul Garcia, Jr., 26; Daniel Garcia, 28; Consuelo Garcia, 45; all of Moultrie, Georgia; and Maria Remedios Garcia-Olalde, 52, a Mexican national. Attorneys for the Garcias declined requests for an interview.

Two of the defendants — the elder Saul Garcia and Garcia-Olalde — also were indicted on obstruction charges for allegedly withholding or falsifying evidence, including trying to keep one of the alleged victims from testifying before a federal grand jury. A trial date has not been set.

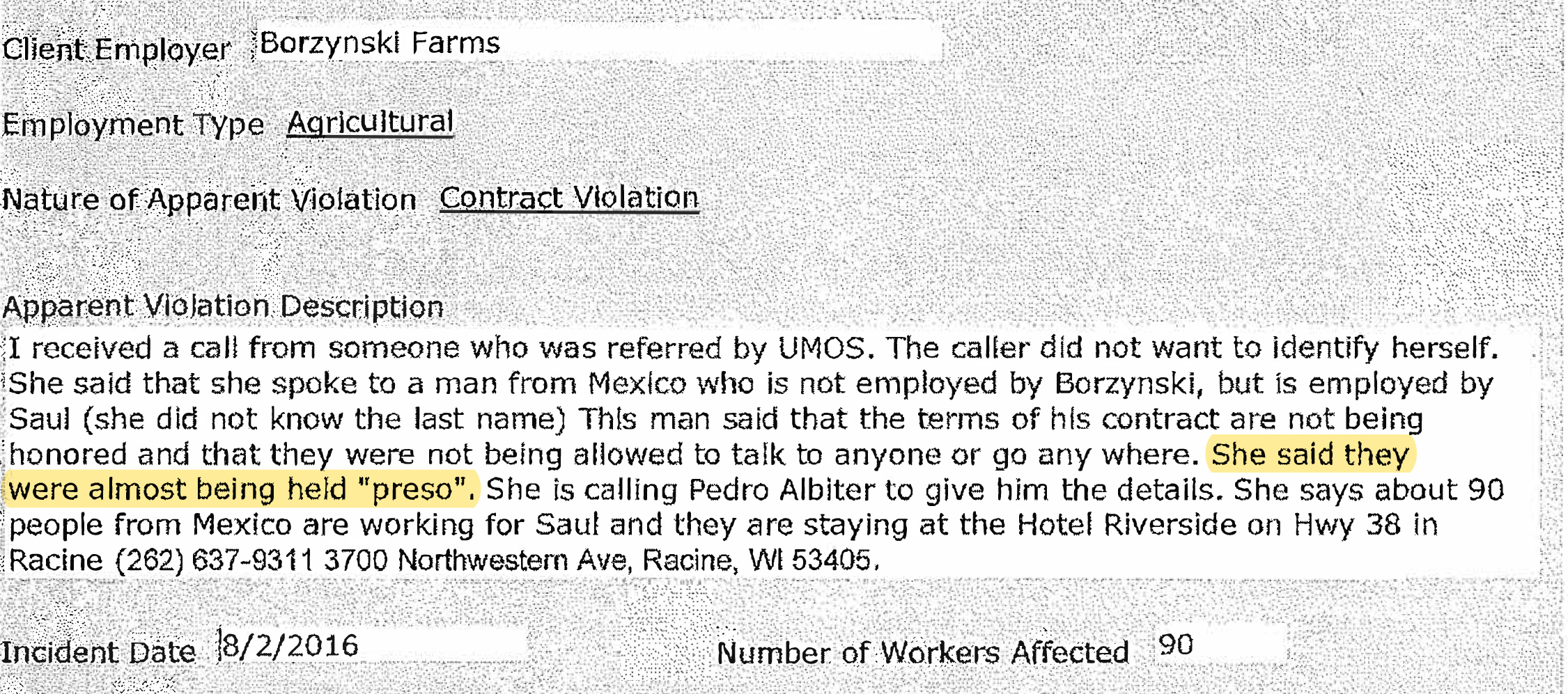

The federal case developed after the state Department of Workforce Development (DWD) investigated the farm in 2016. The UMOS Latina Resource Center in Milwaukee relayed a tip to the state agency that the workers were being held like “prisoners,” according to records obtained under the state public records law.

But spokesman Ben Jedd said the agency was unable to substantiate the allegation after interviewing each worker. DWD did issue a warning to the elder Saul Garcia for preventing workers from cooperating with efforts to investigate the working conditions.

Records indicate federal investigators had already begun their work before DWD ended its inquiry, but it remains unclear who contacted federal authorities. The U.S. Attorney’s Office in Milwaukee declined to describe the origins of the case, which was investigated by the FBI, the U.S. departments of Labor and Homeland Security and the Racine Police Department.

Jedd said DWD, under Gov. Tony Evers’ administration, is “evaluating our current programs and providing educational awareness to our employees” to better detect labor trafficking.

Farm ‘Disheartened’ By Allegations

Owners of the Wisconsin farm where the men worked, Borzynski Farms, said they knew nothing of the conditions under which the men worked or that they were allegedly trafficked.

“Borzynski Farms is disheartened that its fields and facilities may have been used by Garcia & Sons to exploit or cause harm to any worker,” the farm’s attorney, Stephen Kravit, said in a statement.

The farm, which also has operations in Texas, Illinois and Georgia, grows produce including cabbage, sweet corn, leafy greens and green beans.

According to court documents, the Garcias conspired to force the men to work through threats of serious harm, and the workers’ ability to travel was limited by the confiscation of their passports.

Like Roberto, the other workers allegedly paid the equivalent of hundreds of dollars — and sometimes relinquished deeds to family properties — to be put on a list for consideration to be hired for work in Georgia.

“I was thinking of getting ahead. I didn’t know what it was like,” Roberto said.

As they headed to Wisconsin, the men were given fake names and IDs. There, they lived two men to a bed in a motel, and were not allowed to leave without an escort or speak to outsiders, according to court documents. The work was “very hard,” Roberto said.

“We spent all day crouched down,” he said. “Who really knows how our backs took it? Sometimes it rained, and we couldn’t even walk. It got cold, and we were cutting winter cabbage in a heavy, horrible cold. This is how they make you work.”

The men told federal investigators the Garcias yelled at them to work faster and sometimes refused medical help when they were sick. The bosses charged them money to get rides to the doctor. When it was hot, some men passed out in the fields, and the Garcias would not let their fellow workers move them into the shade, investigators were told.

The men said if they felt ill from the heat or fainted, the Garcias yelled at them. If they could not keep up, they were told to sit on a bus without pay.

“Sometimes the manager was angry and didn’t give us water,” Roberto said. “(We) told him that there was no water — it seemed intentional.“

The men said the Garcias charged them between $100 and $150 for a ride to the hospital. A doctor advised one worker he should take a week off, which prompted the Garcias to threaten to send him back to Georgia, court records say.

Roberto said the workers hardly ate and many lost weight. The men said they were not fully compensated for the time they worked. Several men told investigators they had “taxes” taken out of each paycheck, and some said their last few weeks were unpaid — payments that were found to be improperly withheld.

In all, federal agents reported the Garcias failed to pay workers $850,000 in 2015 and 2016.

Prosecutors are seeking to seize from the Garcias nearly $48,000 and up to 15 properties in Georgia, including large homes with spacious yards and an in-ground swimming pool, plus 15 vehicles from model years 2010 to 2018.

Labor Trafficking Rarely Charged

A 2013 Wisconsin Department of Justice assessment found that labor trafficking in the state “often goes unnoticed or not officially investigated because of lack of resources, lack of training, or inability to investigate due to the transient nature of the crime.”

A joint investigation by Wisconsin Watch and Wisconsin Public Radio found that since that report was issued, little had changed, until the Garcia indictment — thought to be the largest labor trafficking case ever prosecuted in the state. In all, just a handful of labor trafficking cases have been charged in Wisconsin’s federal courts.

Wisconsin does rank high among states in its pursuit of human trafficking — which can include trafficking of individuals for sex or labor — according to a 2019 report by the Human Trafficking Institute, a group that studies and combats the crime. But Wisconsin, like many states, has made gains primarily in combating sex trafficking. Of the 16 trafficking cases charged by federal authorities in Wisconsin 2018, 15 were for sex trafficking and just one was for labor trafficking, according to the report.

Enforcement actions short of criminal charges also have been taken in Wisconsin. In June 2018, Georgia-based labor contractor J.C. Castro Harvesting was fined $207,522 after the U.S. Department of Labor found 63 H-2A farm workers living in substandard conditions on Wisconsin crop farms, without access to a kitchen or adequate meals.

Castro was ordered to pay $72,166 in back pay to the workers, who had been transported from a farm in Brinson, Georgia, to work at the unnamed Wisconsin farms. Castro was barred for three years from participating in the H-2A program.

Julie Pfluger, an assistant U.S. attorney for the Western District of Wisconsin, said labor trafficking is often hard to identify.

“If you’re looking for someone who’s black and blue … and says to you ‘Oh my gosh, this guy beat me up and made me work on the farm’ — that’s probably not what you’re going to find,” she said. “You’ll probably end up in something much more subtle where it’s psychological manipulation and coercion. So that’s why it’s harder to spot than you would imagine.”

Pfluger said law enforcement officials are still learning how to identify and prosecute such cases.

“We’re still working on, ‘How do we get into these cases? How do we get in touch with the victims? How do we get them to disclose? How do we train law enforcement to find these cases?’”

According to Catherine Chen, chief program officer of Polaris, a Washington, D.C.-based anti-trafficking group, labor trafficking remains little understood compared to sex trafficking. The victims of labor trafficking are often afraid to report it to the police.

“To better reach victims, law enforcement can build relationships with community leaders and community organizations who may be more likely to hear about labor abuses,” she said. “Law enforcement can also make reporting procedures more accessible in various languages.”

There are windows of opportunity to spot signs of labor trafficking. Health problems, wage complaints and situations in which workers are prevented access to outsiders are all possible signs of trafficking, Chen said.

Workers: We Were Told To Lie

In an interview with WPR and Wisconsin Watch in 2017, Roberto described his journey from optimistic striver to alleged labor trafficking victim.

A few years earlier, Roberto met a man who told him he could make good money working in the United States, doing what he had already done in Mexico: working on a farm.

“He told me, ‘If you want to come to the United States there is work, but first you have to pay (several hundred dollars) and then he’ll put you on a list,’” Roberto said.

At the recruiter’s request, Roberto handed over the title to his parents’ property.

At the U.S. consulate in Monterrey, Mexico, staff asked Roberto and other H-2A applicants if they planned to work in the United States, and if anyone had asked them for money in exchange for entering the country. Several men later said they had been coached to lie in response.

Roberto, like some other workers who were allegedly trafficked by the Garcias, felt he could not stop working while in the United States for fear of losing his parents’ property.

Working In The Shadows

Roberto said the job in Georgia was hard work. Sometimes, buses would pick the men up at their barracks to begin work at 5 a.m. and drive them out to farms in the area. The workers would sleep just a few hours each night. Sometimes, he said, he did not even have time to eat.

Saul Garcia and his sons treated the workers poorly, Roberto said. He said the workers were yelled at, and sometimes they got sick.

“Sometimes the people would pass out working in the sun. Because they don’t let you stop, not even to get some air,” he recalled. “And you feel bad because the people in charge don’t do anything to help them.”

Roberto said the workers were afraid to speak up.

“I looked to see if someone would get up the courage, you know? To do something. But no, we all obeyed,” Roberto said. “That’s how it was, because of the papers and thinking about what you left in Mexico. So, better to keep your head down and handle it.”

About three months after Roberto arrived in Georgia, one of the Garcias came to the workers with news.

“He told us that he was going to send us to work in Wisconsin. And well, we didn’t know anything about that, right? Because it wasn’t in the contract. Supposedly it was just for Georgia, that’s it,” he said. “But at that point, everything he said about the contract wasn’t true, so what could we expect? So he makes you sign the papers with fake names and he takes your photo … and he gives you a fake ID.”

Roberto’s boss told his group of workers that they would need the IDs to cash their checks in Wisconsin. He then drove them in a bus to Wisconsin, where they continued working for several more months.

They landed at a motel in southeastern Wisconsin. Roberto says there were at least four men to a room, two to a bed.

On Nov. 10, 2016, police swooped in while the men were being taken by bus from Borzynski Farms. They expected to be returned to Mexico. Instead, they became witnesses for the prosecution. Roberto remains in Wisconsin.

‘It Is A Heinous Crime’

[[{“fid”:”1036776″,”view_mode”:”embed_portrait”,”fields”:{“format”:”embed_portrait”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3ECatherine%20Chen%20is%20the%20chief%20program%20officer%20of%20Polaris%2C%20a%20Washington%2C%20D.C.-based%20anti-trafficking%20group.%20%3Cem%3EPhoto%20courtesy%20of%20Catherine%20Chen%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Catherine Chen”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Catherine Chen”},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“1”:{“format”:”embed_portrait”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3ECatherine%20Chen%20is%20the%20chief%20program%20officer%20of%20Polaris%2C%20a%20Washington%2C%20D.C.-based%20anti-trafficking%20group.%20%3Cem%3EPhoto%20courtesy%20of%20Catherine%20Chen%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Catherine Chen”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Catherine Chen”}},”link_text”:false,”attributes”:{“alt”:”Catherine Chen”,”title”:”Catherine Chen”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-portrait media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”1″}}]]Chen, of Polaris, said the H2-A visa system ties permission to work in the United States to one specific employer, leaving workers vulnerable to exploitation or at risk of losing their legal status if they quit.

“The fundamental issue we have is if an employer can fully control a worker, that’s highly problematic,” she said. “The threat to them is they will become illegal. They will become undocumented if they try to leave (their sponsor).”

Chen said farm owners should investigate the working conditions of laborers in their fields and should be held accountable, along with the labor contractor, if their workers are trafficked.

Rod Ritcherson, special assistant to the chief officer of UMOS, declined to discuss his agency’s role in investigating the allegations against the Garcias. But he agreed to speak generally about labor trafficking.

“One might think, ‘No, this does not take place in my backyard,’ but the matter of the fact is it is taking place in our backyards, not only in Wisconsin but also across the nation,” Ritcherson said.

He agreed with Chen that legal immigrants working on H-2A visas can be exploited.

“The person is isolated, they are controlled, the employer is responsible for housing that foreign worker, for providing meals, and oftentimes that person is not going to have their own transportation,” he said.

“It is a heinous crime in (the) same category as sex trafficking. To control another human being is despicable,” Ritcherson added. “We hope that justice is brought on behalf of the victims.”

Wisconsin Watch Managing Editor Dee J. Hall contributed to this story. Alexandra Hall and Sarah Whites-Koditschek were Wisconsin Public Radio Mike Simonson Memorial Investigative Reporting Fellows embedded in the newsroom of the nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org), which collaborates with WPR, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.