A federal trial begins on Tuesday in a lawsuit against Wisconsin’s Republican-drawn legislative map, and while it’s not the first such challenge, this one is unique.

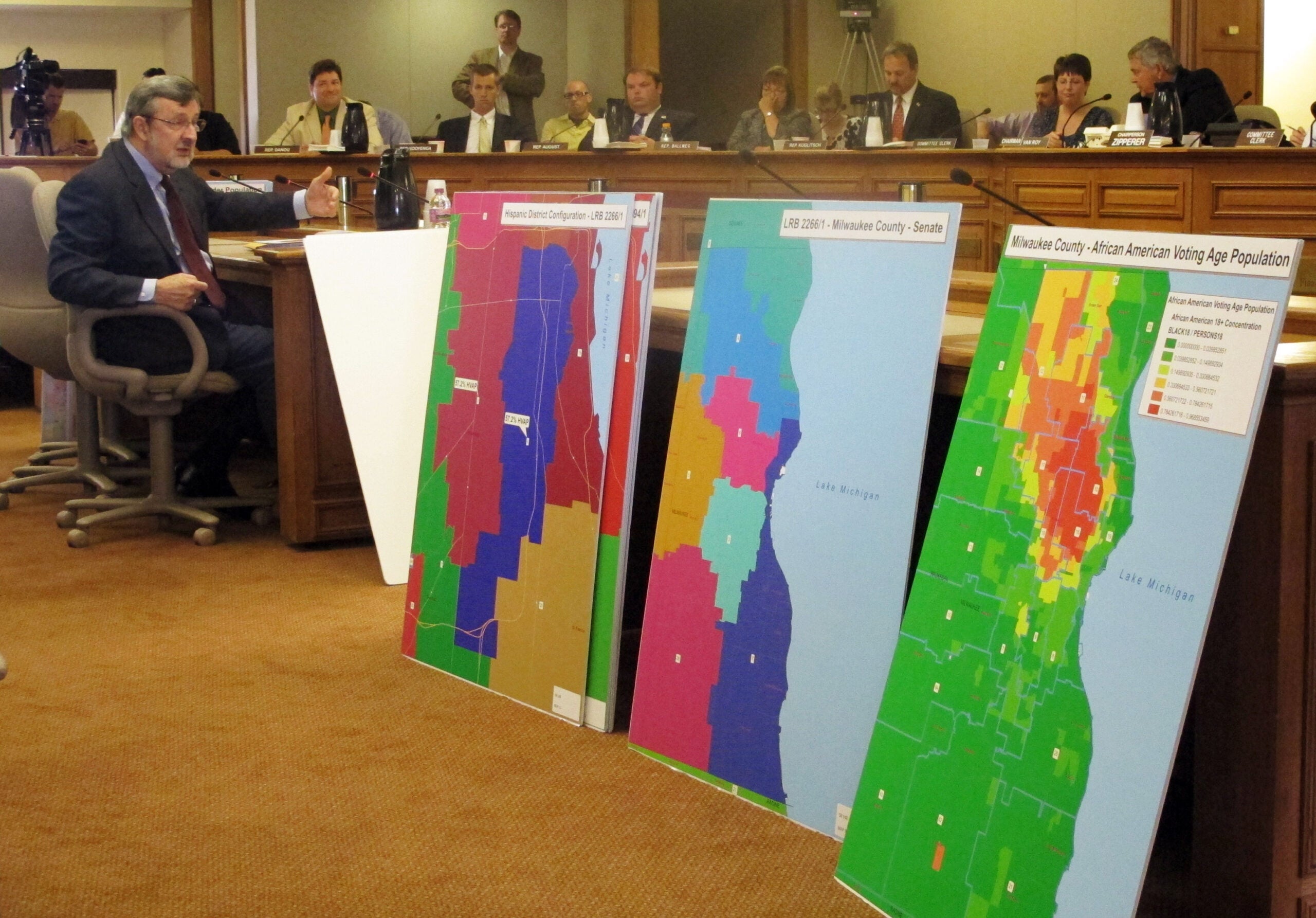

In some ways, Wisconsin has been here before. Republican legislators drew this map in 2011. Democrats sued, and in 2012, a federal judicial panel left most of the map intact.

Under normal circumstances that would be the end of the story. But the case going to trial on Tuesday isn’t normal, and the coalition of groups seeking to overturn the map say Wisconsin’s redistricting experience was anything but typical.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“Wisconsin is the most extreme partisan gerrymander in the United States in the post-2010 cycle,” said attorney Gerry Hebert, who’s the executive director of the Washington, D.C.-based Campaign Legal Center. “It’s about as far out from what you would consider to be fair as you can imagine.”

Legislatures get a chance to redraw their political districts every decade after the U.S. Census. When state government is divided between Republicans and Democrats, they usually don’t agree on a map and the job falls to a court. When one party runs everything in state government, it can draw the map it wants, which is what happened in 2011.

Nobody really disputes that Republicans drew a map that benefits them. What this lawsuit seeks to prove is that Republicans got too partisan, and in the process, violated the constitutional rights of Democratic voters.

“I think we have found the way in this case to really cleanse a big stain on our democracy that has existed for a long time, but has gotten really exacerbated in the last couple of decades where partisan gerrymandering has become the political weapon of choice in the political warfare,” Hebert said.

The fact that a federal court is even hearing this case is a big deal, not only for Wisconsin, but potentially the nation, according to University of California Irvine election law professor Rick Hasen. The last time the U.S. Supreme Court addressed this issue, the court was split on whether to step in and stop partisan gerrymandering; Four justices wanted to intervene and four justices wanted the court to step aside. In the middle was Justice Anthony Kennedy, who was open to the idea if someone could come up with a way to measure how much partisan gerrymandering is too much.

Hasen said this case aims to fill that gap.

“It’s hard to win any partisan gerrymandering case given the history, but what this case … is trying to do is to come up with a new theory that could overcome all of the objections that have been raised so far.”

Essentially, the coalition challenging Wisconsin’s map came up with a new metric to measure partisanship called the “efficiency gap.” Attorney Ruth Greenwood, a redistricting specialist for the Campaign Legal Center, said it compares raw vote totals to actual wins.

“If you look at the total number of votes between the parties, they’re relatively similar. Wisconsin’s a competitive state,” Greenwood said.

It’s when the total number of votes is compared to actual victories in legislative races that Wisconsin becomes an outlier.

Republicans drew the map so that they’re very efficient at making their votes translate to victories. Democrats end up “wasting” votes, either casting far too many of them in races that they were going to win anyway or casting too few in races where they come up just short.

The 2012 election provides one example of how this plays out. Even though Democrats cast far more total votes in all races for the state legislature, Republicans cast more votes where it counted and won more far more seats. The efficiency gap puts a number on this phenomenon, and it’s especially pronounced in Wisconsin.

In addition to the efficiency gap, the lawsuit alleges Republicans took steps that show they intended to silence Democrats, drafting the map in secret and excluding rank-and-file lawmakers from the process. Former Republican state Sen. Dale Schultz and former Democratic state Sen. Tim Cullen have both said the process excluded them. They’re co-chairing the Fair Elections Project, the group that initiated this complaint.

Plaintiffs in the case are Democratic voters like William Whitford, a former University of Wisconsin law professor, who argue the map treats them unequally based on their political beliefs.

“Well it’s very frustrating, of course,” Whitford said. “But also it doesn’t sound very democratic. Basically it’s the apportionment that’s deciding the result of the elections, not the voters.”

The state Department of Justice, which is defending this map, said the plan known as 2011 Act 43 was already upheld under traditional redistricting principles, like drawing districts that are equal in population.

“The plaintiffs have attempted to avoid the question of whether Act 43 departs from traditional districting principles because this is a burden the plaintiffs cannot meet,” wrote Department of Justice lawyers in their final pretrial brief.

The Department is led by Republican Attorney General Brad Schimel. The DOJ also told the court that this case should fail because the “efficiency gap” has no basis in the constitution.

“The plaintiffs’ standard is actually a radical redefinition of gerrymandering because it ignores the traditional understanding of gerrymandering — the drawing of irregular districts,” DOJ attorneys wrote.

The panel hearing this case includes Judge Kenneth Ripple of the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals as well as District Court Judges Barbara Crabb and William Griesbach. Ripple was nominated by President Ronald Reagan, Crabb was nominated by President Jimmy Carter, and Griesbach was nominated by President George W. Bush.

Whatever they decide in the case is likely to be applied to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.