Dozens of Madison residents gathered in a meeting room at a church this spring for an open house about a subject of major controversy: a 39-page document drafted by city planners.

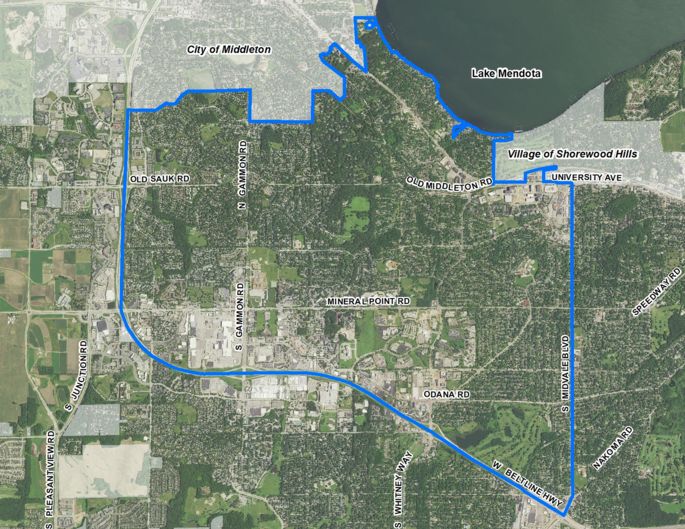

It’s called the West Area Plan — one of 12 such drafts covering different parts of the city to prepare for expected population growth. City planners project Madison will add more than 100,000 residents by 2050. The plan calls for more housing density, more mixed-use development along transit routes and changes to parks and open spaces.

The plan has drawn crowds at raucous public meetings who argue the city’s process has been opaque and the plan is being forced upon residents.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

But not everyone is opposed to the plan.

James and Heidi Jenninga are civil engineers who attended the open house at High Point Church on Old Sauk Road with their 6-month-old baby, Junia. They grew up in the Milwaukee suburbs and North Carolina, respectively, and bought their home on Madison’s west side less than four years ago.

Heidi Jenninga said the neighbors on each side of them have lived there for more than 20 years.

“I think they probably have a different perspective of what that neighborhood culture is, and what it could look like in the future if we have to change,” she said. “I think we have a more broad perspective.”

She pointed to a proposal to reduce the number of traffic lanes and add shared-use paths on Gammon Road as a reason for her young family to stay in the neighborhood.

“We’d love to take her in a Burley on a trailer bike and right now we can’t do that safely,” she said.

Sharon Genthe has a very different view. Genthe said she’s lived in the Middleton and Madison area for 50 years.

“I had a vision that I wanted to live in the neighborhood I live in now, back in 1984. And I had to buy and sell properties, work up the ladder for jobs, so that I could eventually live here,” Genthe said.

She finally bought her dream home 12 years ago, she said, “and then this happened.”

Among her fears of what the changes could bring, Genthe listed potential high-rise buildings, the addition of so-called granny suites and the elimination of groups of single family homes. She said the city is prioritizing “future people.”

“Well, I was a future person once. And I had worked hard to get here. Now I don’t want it taken away or changed or traffic increased or (to) pay for somebody else to come,” she said.

Genthe, like many opponents of the plan, questions the city’s population projections or whether Madison’s housing crunch even qualifies as a crisis.

‘Slow burning crisis’ fueled by low vacancy rates, among other metrics

Kurt Paulsen said he can understand that perspective, because for current residents, the market seems to be in good shape.

“We’ve lived in our house for a long period of time, it’s gone up in value,” said Paulsen, a University of Wisconsin-Madison professor of urban planning. “And we refinanced our mortgages at less than 3 percent. So for the majority of people who are already here, it does not look like there’s a housing crisis, right?”

But Paulsen, who researches housing policy and has written two of Dane County’s housing needs assessments, has many data points ready to illustrate the extent of the housing problem.

“It’s a crisis, but it’s a slow burning crisis that’s come on over the last 15 years,” he said.

“We can look at any number of metrics, one of which is vacancy rates — how much housing is available. And for both rental and ownership for sale housing in Dane County, and Madison, we’re way below historical norms and what is considered a balanced market,” Paulsen said.

The rise in interest rates as well as the rise in housing construction costs coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic “added fuel to a simmering fire,” he said.

Affordable and available housing is also top of mind for voters in Wisconsin. As part of WPR’s America Amplified project, we’re asking people what elected officials could do to improve their communities. And multiple people wrote to us saying housing is the most important issue facing the state.

The most recent Housing Snapshot Report on the city of Madison from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development found Madison’s rental vacancy rate is “still well below healthy levels” required to stem the rising cost of rent.

“With demand exceeding supply, as well as drastic increases in construction cost, almost all new rental units are unaffordable to the median renter household as they open, even though they will eventually be relatively affordable,” the 2023 report states.

Homeowner vacancy rates are even lower — falling below 1 percent in recent years.

Vacancy rates aren’t the only metric that show a housing crisis, Paulsen said.

“You can look at changes year-over-year in rents. You can look at changes in the rent burden, how many families are paying more than half of their income to rent,” he said. “And then you can look at numbers of homeless children in public schools. And then the literal count of homelessness from the January Point in Time Count.”

“Every one of those indicators is trending in the wrong direction and showing a crisis,” he added.

Housing crunch could worsen as more people look to call Madison home

Madison’s population has grown greater than prior estimates. In 2013, the Wisconsin Department of Administration projected the city’s population would be just over 250,000 in 2020, and its 2030 population to be a little more than 270,000.

But the 2020 Census showed Madison’s population was 269,840 — barely shy of where the state expected it would land 10 years later.

“That’s why the city is trying to get ahead of things and recognizing that we need to increase our forecasts. But ultimately, it’s going to be the development community that also looks at these demographic and economic forecasts,” Paulsen said. “And they are telling us that they see a huge demand for housing in Madison and Dane County and they want to build more housing.”

Part of the problem is a clear mismatch in supply and demand for different types of housing. In the rental market, Madison has a shortage of the housing at every price range, according to the snapshot.

That means people at the lowest income level have to use a greater share of their income to be able to find a place to live. It also means households at the highest income level end up renting units that are incredibly affordable to them, taking that housing off the market for those with lower incomes.

Amy Kell has spent her career advocating for affordable housing. She’s also lived in cities with growing populations and tight housing markets, like Seattle and Atlanta. Both of those cities had faster population growth than Madison, and a lot more land to build housing and transit routes.

“Madison is constrained by the four lakes … you can’t build housing on a lake,” she said. “We don’t have as much land as another city might have.”

Kell is now an active citizen in Madison, where she moved for an early retirement. She said the concern for many people she knows is not displacement from new residents, but a loss of their neighborhood’s tree canopy.

“Trees are coming down for any number of reasons — for bike paths or (because) they tried to jam in a building,” she said, “And dozens and dozens of old trees have come down. And I think that really does affect the quality of our life in a negative way.”

Kell spent the last 22 years of her career running a consulting company that worked to get more funding for both affordable housing and providing social services for low income residents and seniors. She said there are plenty of opportunities for affordable housing within a reasonable drive from jobs in downtown Madison.

“I worked in affordable housing my whole career, I believe in it. And I believe it gives people a leg up. But I also think that you have to balance it out with the market conditions of the city that you’re dealing with,” she said. “And the geography of the city that you’re dealing with.”

Paulsen, the UW-Madison housing expert, said he’s not sure how to break through the divisions between neighbors. But he said it’s ultimately a moral question.

“‘Are the people who cook your food or take care of your kids or drive the bus or cut your hair, are they able to live in the same neighborhood and send their kids to the same school as you do?’” he said.

“Do we think that everyone deserves a decent and affordable place to live? And are we willing to say yes and make room for more people in our neighborhood?”

This story is part of WPR’s work to connect with and better serve Wisconsin’s voters this election season. We want to know what information you need about how to vote. What do you wish candidates were talking about? Tell us what issue matters most to you and your community here.

More reporting from WPR’s America Amplified initiative is available here.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.