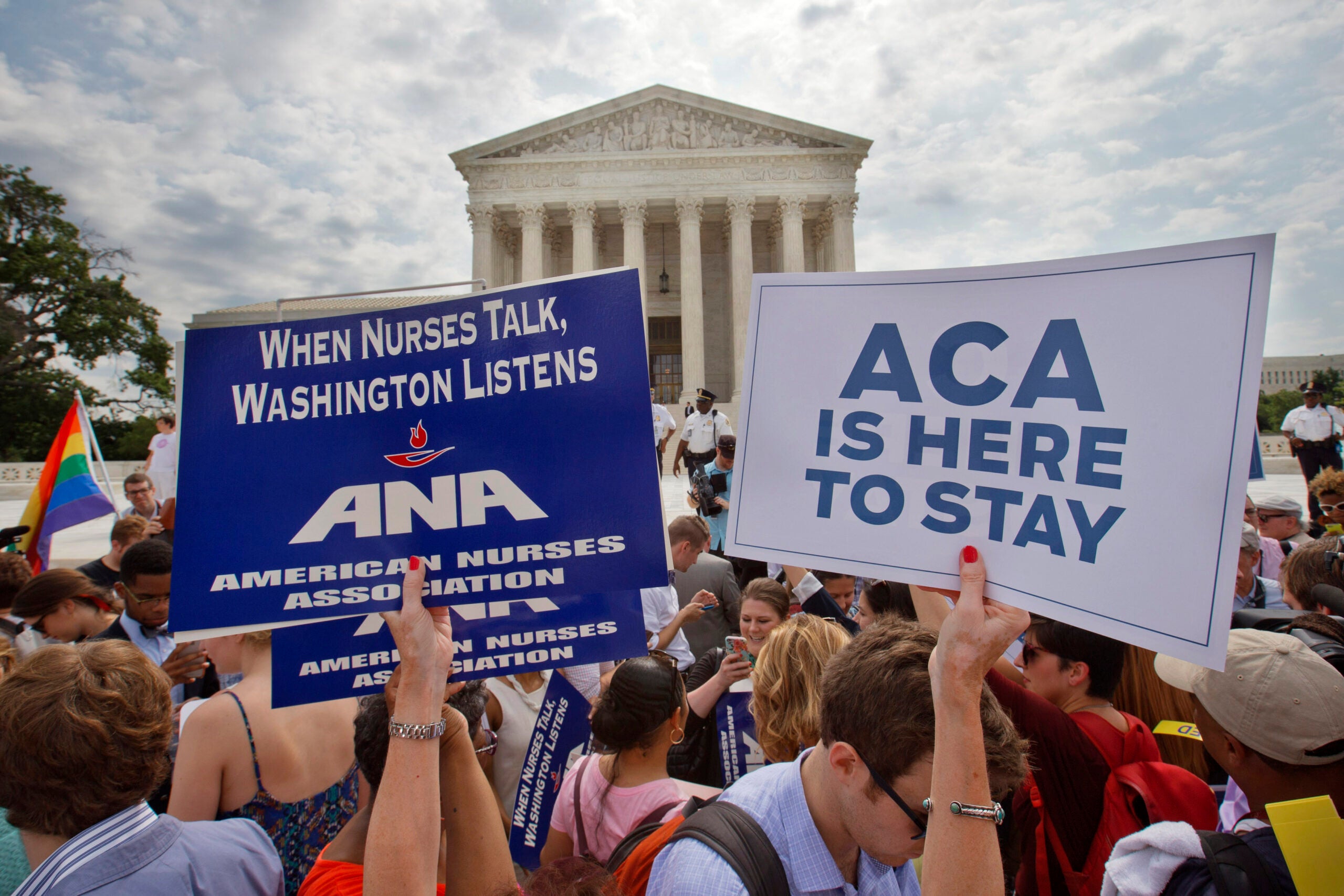

Consumers, insurance companies and health care providers are experiencing déjà vu. Politicians are once again attempting to make big changes to the nation’s health care system.

Back in 2009, it was President Barack Obama and his fellow Democrats pushing a major overhaul with the Affordable Care Act. This time Republicans are in the driver’s seat, looking to repeal and replace that legislation, commonly called Obamacare. But there’s disagreement within the GOP over how fast they should go in dismantling it and where they’ll end up.

Among those likely facing the most uncertainty are self-employed workers, many of whom were able to get coverage more easily under the ACA.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Most Americans get health insurance where they work, which can create a predicament known as job lock: Workers are stuck in less-than-ideal jobs because leaving would mean they’d lose benefits.

In 2008 — a year before Obamacare was passed in the senate — a Harvard Business School study estimated job lock affected 11 million people. While similar numbers aren’t readily available for more recent years, workers like 30-year-old Sadie Tuescher of Wauwatosa credit the ACA with freeing them from job lock.

Sadie Tuescher.

In 2015, two years after the federal health care marketplace was up and running, Tuescher bought coverage for herself and started a business.

“I have always wanted to work for myself and be an entrepreneur,” she said.

Tuescher formerly worked as a disability benefits specialist for Milwaukee County and also as an elder benefits specialist for a nonprofit law firm. Now she’s an independent insurance agent

“I love the independence of it,” Tuescher said. “I love making my own hours. Deciding the direction of my business is amazing.”

Before the ACA, getting insurance could be difficult. When Tuescher was laid off from her job at the nonprofit in her mid-20s, she tried to get individual coverage and was told she had a pre-existing condition.

“My pre-existing conditions were small things,” she recalled. “I had hurt my ankle in a hiking incident and had to have physical therapy for it. The issue was resolved but it was still considered a pre-existing condition.”

She also had been on an anti-depressant after a family member died. Because of these two pre-existing conditions, Tuescher said, she was denied the insurance she sought and offered a less comprehensive plan.

Even though this was before the ACA, some insurers allowed adult children to stay on their parents’ plan until age 26. That’s what Tuescher did.

It’s a popular provision of Obamacare and President-elect Donald Trump has said he supports it. But if young people can be on their parent’s insurance, they’re not purchasing their own coverage.

Wisconsin state Rep. Joe Sanfelippo, R-New Berlin, argues this is an example of how the ACA is “unsustainable” and was “not well thought out.” At a Wisconsin Health News forum earlier this month, Sanfelippo, chair of the state Assembly’s health committee, said it’s a “great benefit” but it undermines the insurance market.

“You want those young, healthy people buying insurance and paying premiums,” he said. “You’re shooting yourself in the foot when you allow them to be on somebody else’s plan until they’re 26.”

So Republicans have a dilemma: scrap all of Obamacare or save some of it. Keeping adult children on parent’s insurance is popular but costs money. Trump has promised a replacement health plan that will cover everybody, have lower deductibles and cheaper drugs, but hasn’t offered specifics about how it would work or be paid for.

Meanwhile the GOP-dominated U.S. House of Representatives has laid the groundwork to repeal Obamacare. But there’s no consensus on a replacement or when it might take effect. That makes some who rely on the marketplace, like Tuescher, nervous.

“I always tell clients it’s kind of a game that we play,” she said. “We’re betting on our own future health. And the Affordable Care Act sets mandated limits for an individual’s out-of-pocket spending. Before the Affordable Care Act, it was the opposite.”

In other words, patients were on the hook for bills until they went bankrupt. Before the ACA, insurers could stop paying after a certain amount, usually a $! million over a lifetime of benefits.

Patients without insurance are a problem for health care providers too. Mike Wallace is CEO of Fort HealthCare. During a panel discussion in Madison put on by Wisconsin Health News Jan. 12, he said he’s seen a lot of changes in the industry and he’s preparing for more by channeling his inner Aaron Rodgers from the Green Bay Packers: “I tell people to R-E-L-A-X. Seriously, little perspective on this on the front lines.”

Wallace says if Obamacare is repealed, people will still need care. And he said it’s the industry’s job to ensure they get it.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.