Larry Meiller visits with Patty Loew about members of each of Wisconsin’s Native American tribes. Find out about their unique cultural traditions, tribal history and life today.

Featured in this Show

-

Author Shares Story Of Wisconsin's Unrecognized Indian Nation

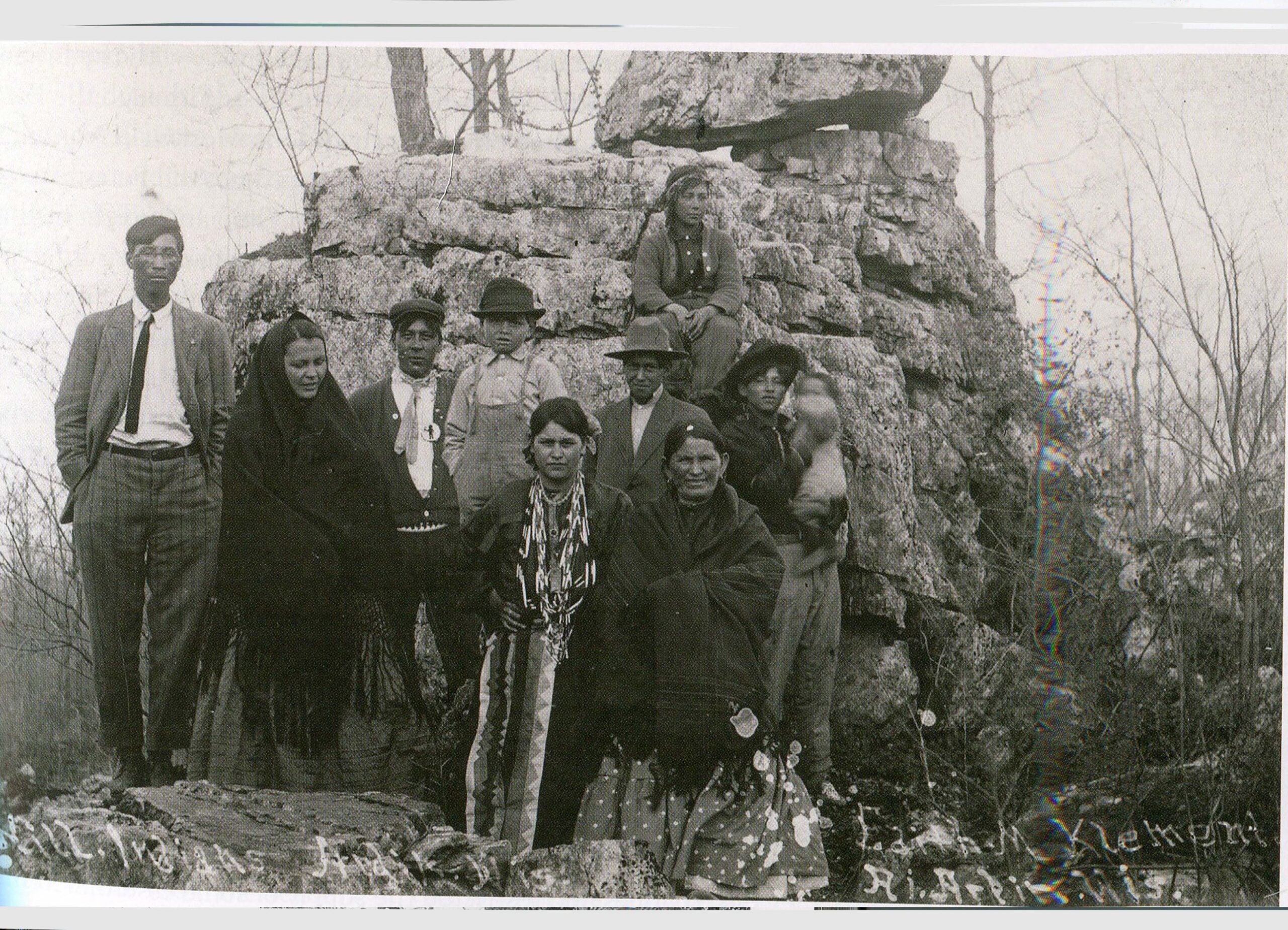

Wisconsin is home to 12 native nations in the state of Wisconsin, but as University of Wisconsin professor Patty Loew explains, only 11 are recognized federally. In addition to six bands of the Ojibwe, along with the Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, Oneida, Mohican, and the community that lives in urban areas called Urban Indians, there is a tribe known as the Brothertown, whose determination to stay in Wisconsin cost them their official status.

In the new edition of her book, “Native People of Wisconsin,” Loew, herself an enrolled member of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe, explores facets of all 12 of the state’s native nations, including the relatively unknown history of the Brothertown.

“The Brothertown are an interesting tribe because they’re an amalgamation of several tribes, some of whom were largely wiped out in the 16th and 17th centuries out east,” Loew said.

By the late 1700s, many Christian Native Americans in New England had coalesced into so-called “praying towns.” After the American Revolution, Loew said, several tribes decided to form their own community based on peace and brotherhood, which is where the name Brothertown came from.

The Brothertown received land in upstate New York, alongside local Oneida peoples, but with the encroachment of land-hungry European Americans, it became a temporary home.

“All these tribes that were living in what we would call New York state now were being pressured to move out west so the Brothertown moved west with the Oneida and the Mohicans,” Loew said.

In the 1830s the tribe had landed in Wisconsin but faced many of the same pressures that had forced them out of New York.

With policies like the Indian Removal Act in 1830, Loew said, the Brothertown feared they would be pushed off of their lands again and would be forced to move farther west still, to Kansas or Oklahoma.

“They thought the best way to hold on to their land was to accept citizenship. They didn’t realize in accepting citizenship they were also accepting termination so (their tribal status was) terminated by an act of Congress in 1839,” Loew said.

Now, the money and resources that the government gives to recognized Indian Nations were not accessible to the Brothertown.

In recent decades, the Brothertown worked with the Bureau of Indian Affairs to be restored as an Indian nation were unsuccessful. As low put it, the BIA said that “… because you were terminated by an act of Congress, it’ll take an act of Congress to reinstate you.”

But even without recognition, said Loew, the Brothertown Nation still has thousands of members who call Wisconsin home, mostly in the Fond du Lac area, with a government body and efforts to preserve cultural traditions.

Episode Credits

- Larry Meiller Host

- Cheyenne Lentz Producer

- Patty Loew Guest

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.