Despite the constant media attention the Zika virus has received so far in 2016, University of Wisconsin-Madison pathologist David O’Connor thinks people shouldn’t panic.

“Fear and uncertainty is a toxic stew, and one of the things we have to do is make sure we’re guided by science,” he said.

O’Connor and his team of researchers are trying to do just that: figure out the science behind Zika, the mosquito-borne illness that is likely linked to birth defect cases and other neurological symptoms.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

O’Connor’s work on Zika started this past October on a visit to Brazil, where he does a lot of his research.

“One of my colleagues … pulled me aside and told me there had been these reports of a small number of babies born with small heads in the north of Brazil,” he said.

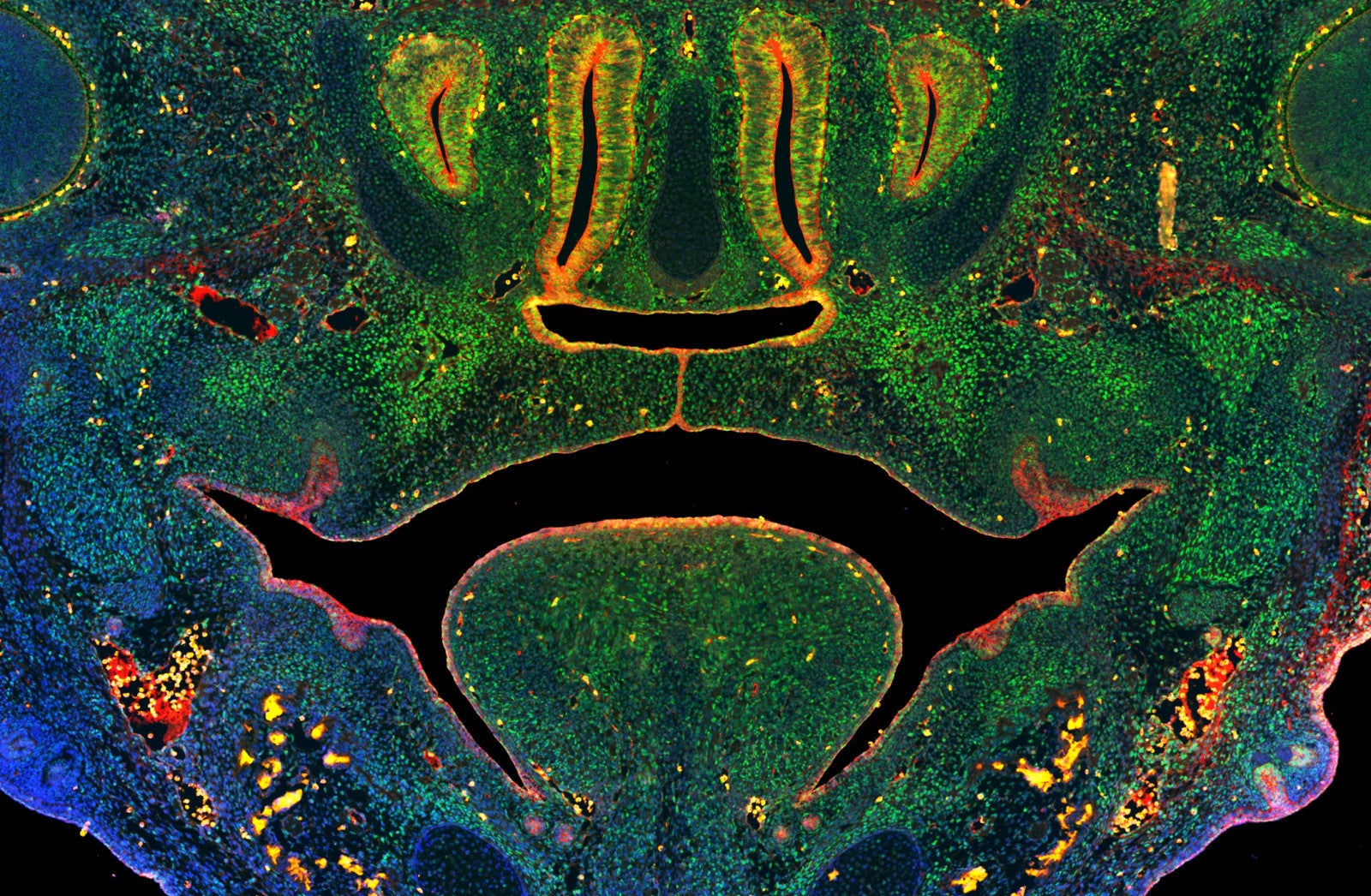

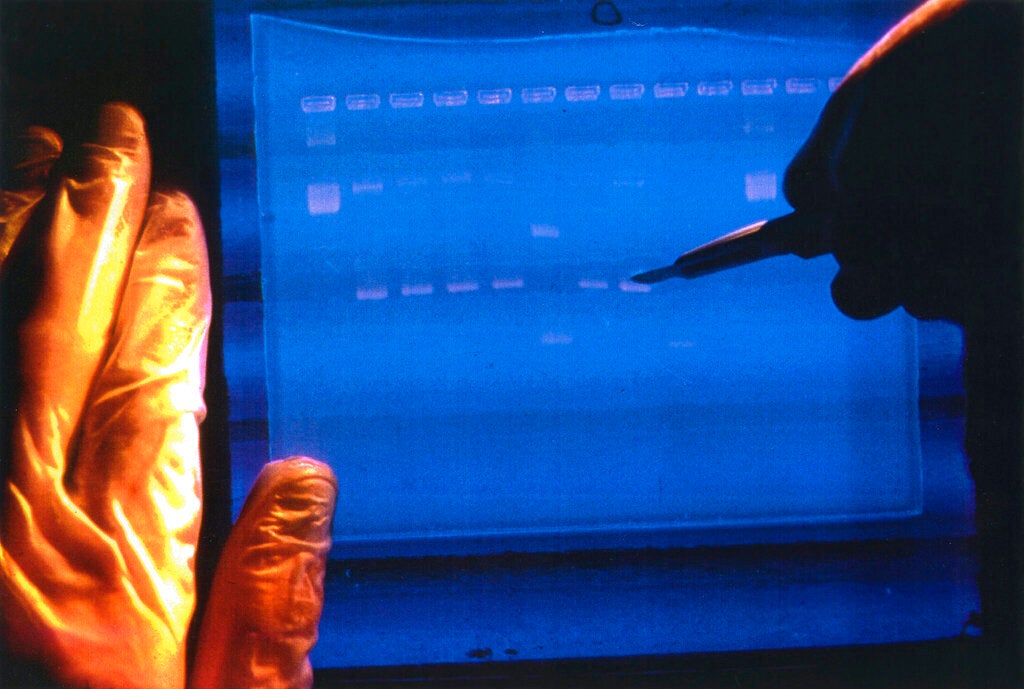

Genetic testing by O’Connor’s lab showed strong suspicion that the Zika virus was playing a role in the increased occurrence of microcephaly, a birth defect that causes babies to be born with small heads.

But acknowledging that the virus could cause birth defects was just the first hurdle. O’Connor said there’s still a lot of uncertainty about how the virus affects a developing fetus.

“If you’re infected with Zika right before you give birth, is that as bad or better or worse than if you’re infected early in development during the first trimester?” he said.

O’Connor and his team of researchers are now leading some of the first experiments on monkeys to better understand how the disease affects pregnancy.

“The reason we want to make an animal model is because we have unique expertise and unique resources here at Wisconsin,” said UW pathologist Thomas Friedrich, one of O’Connor’s partners.

Researchers have collaborated with UW obstetricians and the Wisconsin National Primate Center to launch a pregnancy study on rhesus macaques, a heavily studied species of monkey that has physiological similarities to humans.

“The idea is to infect macaques during the first, second and third trimesters of pregnancy and compare how zika infection at different stages of pregnancy impacts development,” O’Connor said.

The virus is typically spread by mosquitoes, but cases have been reported of people contracting the disease through sex. It can be marked by fever and fatigue, although 80 percent of people who get the virus show no symptoms at all.

Friedrich said even though the virus was first discovered in the 1940s, the lack of symptoms prevented it from getting sufficient attention from the scientific community.

“We haven’t noticed the link before between the Zika virus and birth defects, and it could be that’s because the virus has evolved in some way and now it causes these problems where it didn’t before,” he said.

O’Connor thinks another explanation for why the virus has gone unnoticed is because of similarities it shares with a common ailment that affects children in the United States.

“Many people like myself were deliberately exposed to chickenpox when we were young in the hope that that would protect us from chickenpox when we were older,” O’Connor said. “Because of the type of virus that Zika virus is, there is good reason to believe that exposure to Zika virus once is going to protect you from subsequent reinfection.”

Along with studying the effects on pregnancy, researchers will be testing to see if the monkeys develop immunity to the virus.

Cristina Cassetti, program officer in the virology branch of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said that’s a major question that needs to be answered.

“That could mean women in childbearing age that have already been infected with Zika … they probably are going to be immune to the infection,” she said.

O’Connor predicted much more will be known about the virus by the end of 2016.

“I believe that zika virus is probably going to generate a first-year record for the most amount of research that’s done on it,” he said.

The research team at UW will be making their data available in real time as they collect it, sharing their findings with scientists around the globe.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.