Want to feel better and look your best?

This isn’t a pitch for another diet fad or workout program. It’s more of an affirmation, backed by science, that mind and body wellness is within reach — you’ve just got to hold out a helping hand.

Drs. Stephen Trzeciak and Anthony Mazzarelli explain the data behind how serving other people is its own form of medicine in their new book, “Wonder Drug: 7 Scientifically Proven Ways That Serving Others is the Best Medicine for Yourself.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Those benefits include greater longevity, blood pressure control, fewer heart issues, less depression and better sleep and willpower.

“What the science supports is that rather than going deeper into ourselves — which some of the self-help or ‘me time’ proponents suggest — really to get out of our own head, to focus on others and serve other people is the best way to achieve all of these outcomes that we want for ourselves in terms of health and well-being,” Trzeciak said during an appearance on Wisconsin Public Radio’s “Central Time.”

The effect in the body when we help others — boosted neurotransmitters and hormones and an activated parasympathetic nervous system that relaxes us — form a sort of buffer against stress in the moment, in addition to chronic stress that’s associated with myriad health challenges, Trzeciak said.

Chronic inflammation is another health challenge that helping others protects against.

“Serving others actually can switch off the genes in such a way to reduce the production of chronic systemic inflammation,” he said.

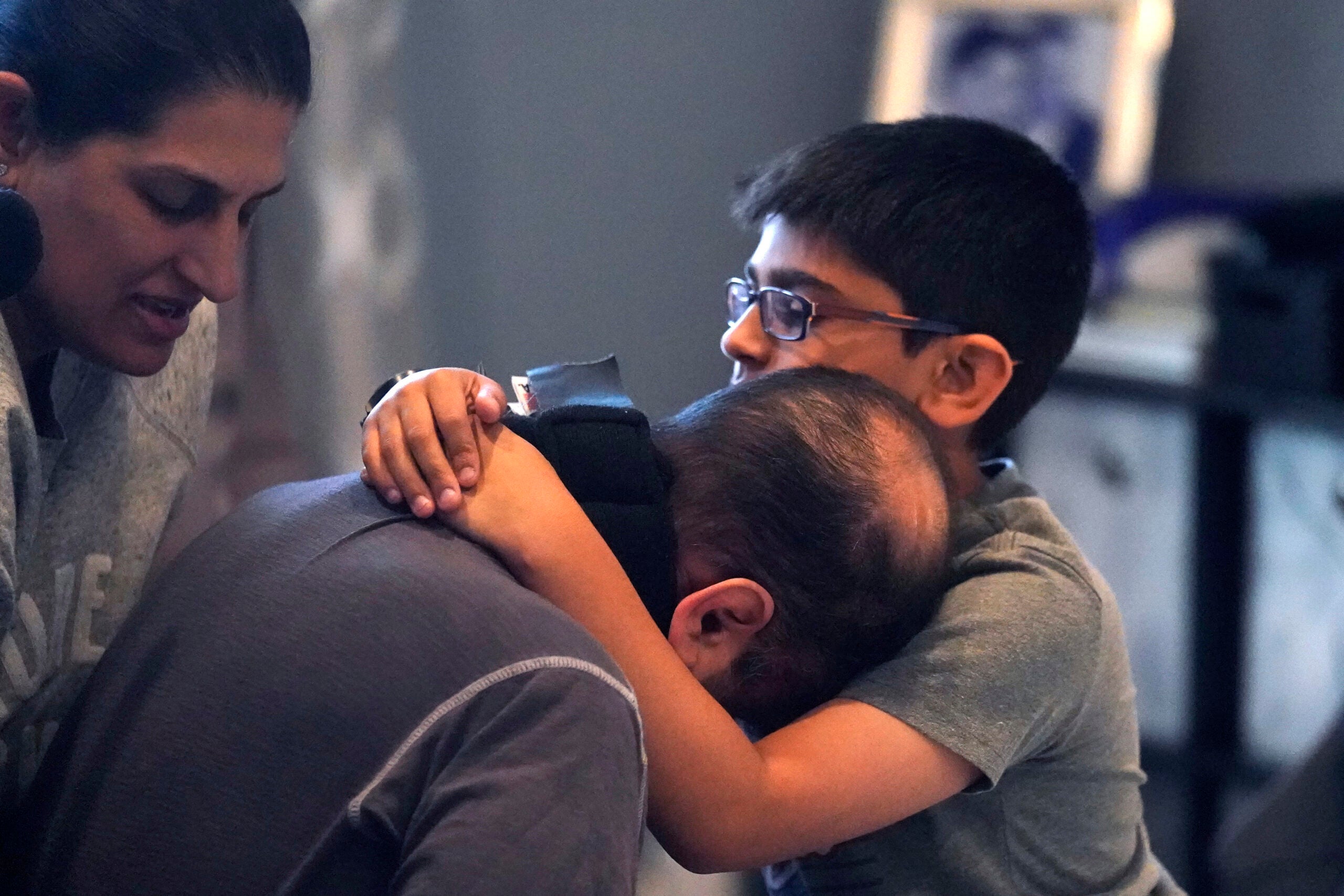

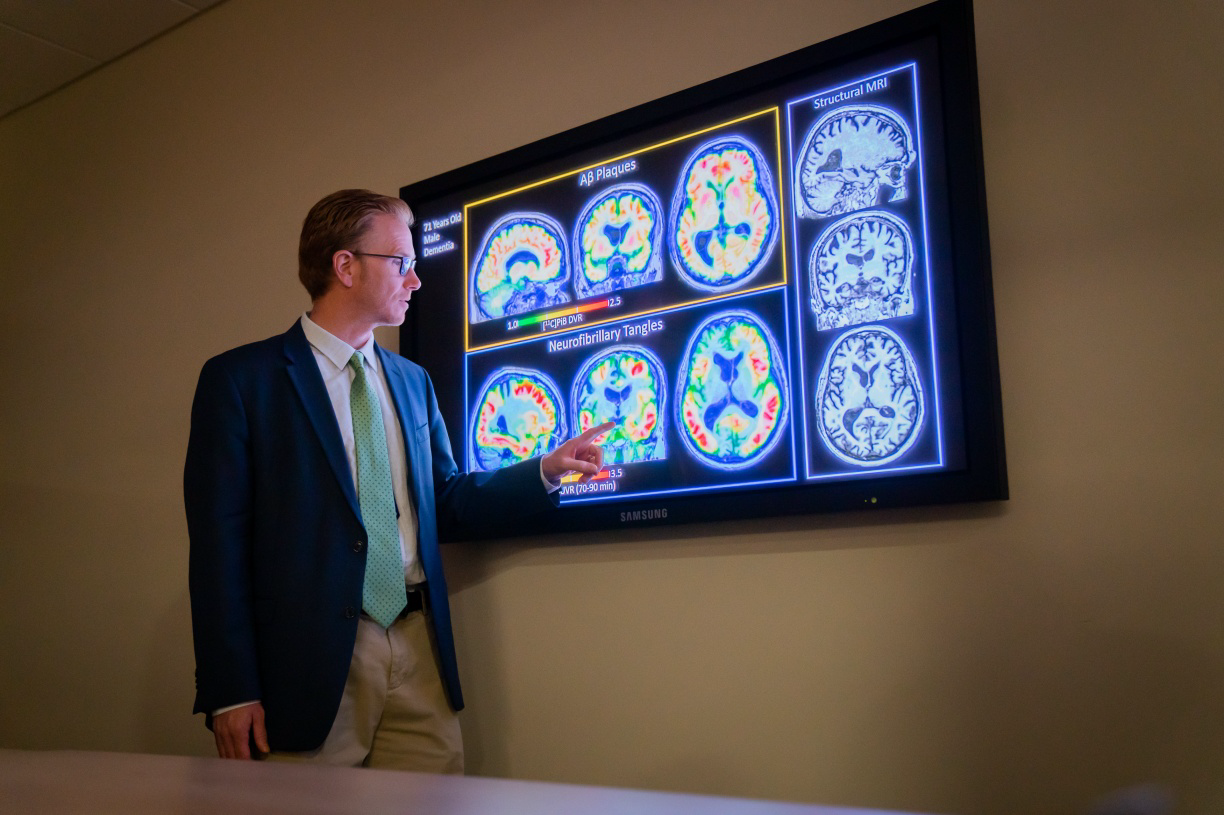

Data parsed by the doctor duo showed that during functional MRI brain scans, pain centers in our brains are activated when we see someone struggling; conversely, the reward centers of our brains are triggered when we take action to alleviate someone else’s pain and suffering.

Trzeciak, chief of medicine at Cooper University Health Care, and Mazzarelli gleaned data from 250 peer reviewed research studies to study the physical impacts of helping others. They then developed a seven-step prescription to follow to unearth some of these benefits.

One of those prescriptions is to start small. A way to do that, Trzeciak said, is by changing the way we interact with our surroundings. Maybe that means helping a coworker or serving the people with whom we share a household.

“It’s just on average 16 minutes per day of service to others that will give us the benefits as it relates to longevity,” he said.

Helping other people shouldn’t come at the expense of taking care of ourselves, though.

“Being self-focused and being other-focused are not two extremes on one single continuum,” Trzeciak said. “What researchers have shown is that there are actually two independent axes, meaning you can be high or low on both.”

Trzeciak said the most benefit is derived from being a “live to giver” — someone who actively helps other people and pays close attention to their own needs.

“Those people are high on other interest, but they can also be high on self-interest in the way that they know it’s good for them, and it makes them happy,” he said. “And that’s OK if you realize that … actually doesn’t ruin the effect.”

The research, according to Trzeciak, shows people have on average nine opportunities each day to be empathetic. Whether that’s assisting your spouse with a home project or helping a stranger load up their groceries, it all makes a difference.

But, if you’re helping for notoriety or to receive something in return, you’re not going to see gains.

Trzeciak and Mazzarelli call these types of people “live to getters” and said that offering a helping hand in hopes of getting something in return is a form of strategy that activates a different part of our brains.

“If … you’re serving somebody because it’s not only going to make you look good but maybe in order to get something in return in like some sort of reciprocity, research shows quite clearly you might as well forget it,” Trzeciak said. “It just doesn’t work.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.