The strip of land known as Wisconsin Point juts out from the east side of Superior into Lake Superior. The sandbar spans more than 200 acres and stretches nearly 3 miles along the lake. A lighthouse at its western end marks the entry to the Superior port.

Some 400 years ago, the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa settled there. Two centuries later, they were a vibrant community led by Chief Joseph Osaugie. At least seven generations of tribal members were laid to rest there, including Osaugie.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

For years, the Fond du Lac Band has worked to bring lands there back under tribal ownership. The most recent effort centered on returning the tribe’s burial grounds. It was an effort that finally succeeded in July when the Superior City Council approved the transfer of Wisconsin Point burial grounds to the tribe.

This month, descendants of Osaugie gathered at the tribe’s ancestral lands to reunite. And last Thursday, the city officially signed over a small plot on Wisconsin Point. A community celebration marked the return of the tribe’s burial sites.

Osaugie was among Ojibwe chiefs who traveled to Washington D.C in 1852 to fight a presidential order seeking to force them from their homelands. The trip resulted in the 1854 treaty that established reservations in northern Wisconsin and Minnesota, including for the Fond du Lac tribe.

Decades later, the tribe’s ancestors, including those living and those who were long buried, would be removed from their homes and final resting places. In 1918, U.S. Steel dug up remains from nearly 200 Ojibwe graves to make way for ore docks that were never built.

“They took 198 graves, and they moved them by scow (a type of barge) down the Nemadji River to St. Francis Cemetery where then they put them into graves there,” explained Superior native Lorrie Madden, a 66-year-old descendant of Osaugie.

The remains were reburied in around 30 mass graves at St. Francis Cemetery in Superior, with the removal paid for through federal funds intended for tribal members. That sort of treatment was not unusual at the time, but tribal members today argued that it was an injustice that Superior could address by returning lands to the tribe.

In the early 20th century, a Douglas County court ruling granted U.S. Steel ownership of lands at Wisconsin Point, but the tribe’s ancestors retained rights to the burial grounds. The company and city of Superior later appealed that decision to remove any barriers to development, eventually stripping all lands from Ojibwe residents there.

‘Our roots are here’: Chief Osaugie’s descendants reunite

On Aug. 6, as still waters on Lake Superior lapped against the shoreline of Wisconsin Point, around 50 people filtered by a table full of food and filled plates with hot dogs, burgers and sweet corn before gathering around a fire in the shade.

The reunion of Osaugie’s descendants has been held here every year for nearly two decades now. Even so, some people are meeting relatives for the first time, like Kimberlee Mitchell of Iron River.

“I’m going to be 66 years old, and I know nothing of my heritage,” said Mitchell. “With the land transfer back, we thought, we’ve got to be here.”

Colleen Aird, who just turned 99 years old, said the return of the tribe’s burial grounds to Wisconsin Point is overwhelming.

“This is really home,” she said. “Our roots are here.”

Aird shared stories from her father about what life was like for him as a child on Wisconsin Point, which once had a small village and one-room schoolhouse.

“They had a potbellied stove when it was cold, and he would have to build the fire in there to warm up the school room,” recalled Aird. “And then he’d have to row the boat over to Superior, and the teacher was waiting there. Then he’d row back over here.”

Osaugie descendant Bob Miller, a Superior native who lives in Hermantown, said his grandmother lived on Wisconsin Point. She would tell him stories about men fishing for herring.

“They would go out on the lake, and they would come back here. Grandma and the kids would go down and help unload the boats,” Miller said.

His grandma also told him her mother used to make dolls out of buckskin. As he recounted the story, that jogged a memory for Aird about her grandma making moccasins.

The stories passed down are treasured memories for the family. Lorrie Madden said the history of this place was lost to her and others.

“My mom and dad did not share stories with us because of the fact of discrimination,” Madden said.

Madden and others recounted how their parents withheld details of their Native ancestry out of fear.

Aird said her mother, Mary Ann Lillian Durfee, went to an Indian boarding school in Bayfield. During that time, such schools focused on eliminating cultural practices and barred children from speaking their own language. Experts also estimate thousands of Indigenous children died at Indian boarding schools across North America. Last year, remains of more than 200 children were discovered at a boarding school in Canada.

Within weeks of that discovery, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland announced the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, which investigated federal policies around boarding schools and burial sites linked to them. The federal investigation found more than 400 schools in 37 states, including 11 schools in Wisconsin. More than 50 schools nationwide had marked or unmarked burial sites. Last fall, Gov. Tony Evers apologized for the state’s role supporting those boarding schools.

While the Bayfield school didn’t claim the life of Aird’s mother, the family lost their culture and language. Now, Aird’s granddaughter Veronica has been learning more about their heritage and studying the Ojibwe language.

“She’s kind of bringing us back to those traditions,” said Pat Nelson, Aird’s daughter.

As part of their culture, Miller said tribal members make decisions based on how they will affect seven generations into the future. Now, he highlighted the seventh generation of Osaugie’s family tree is finally seeing the tribe’s burial grounds returned to their rightful owners.

Fond du Lac tribe marks return of sacred burial grounds

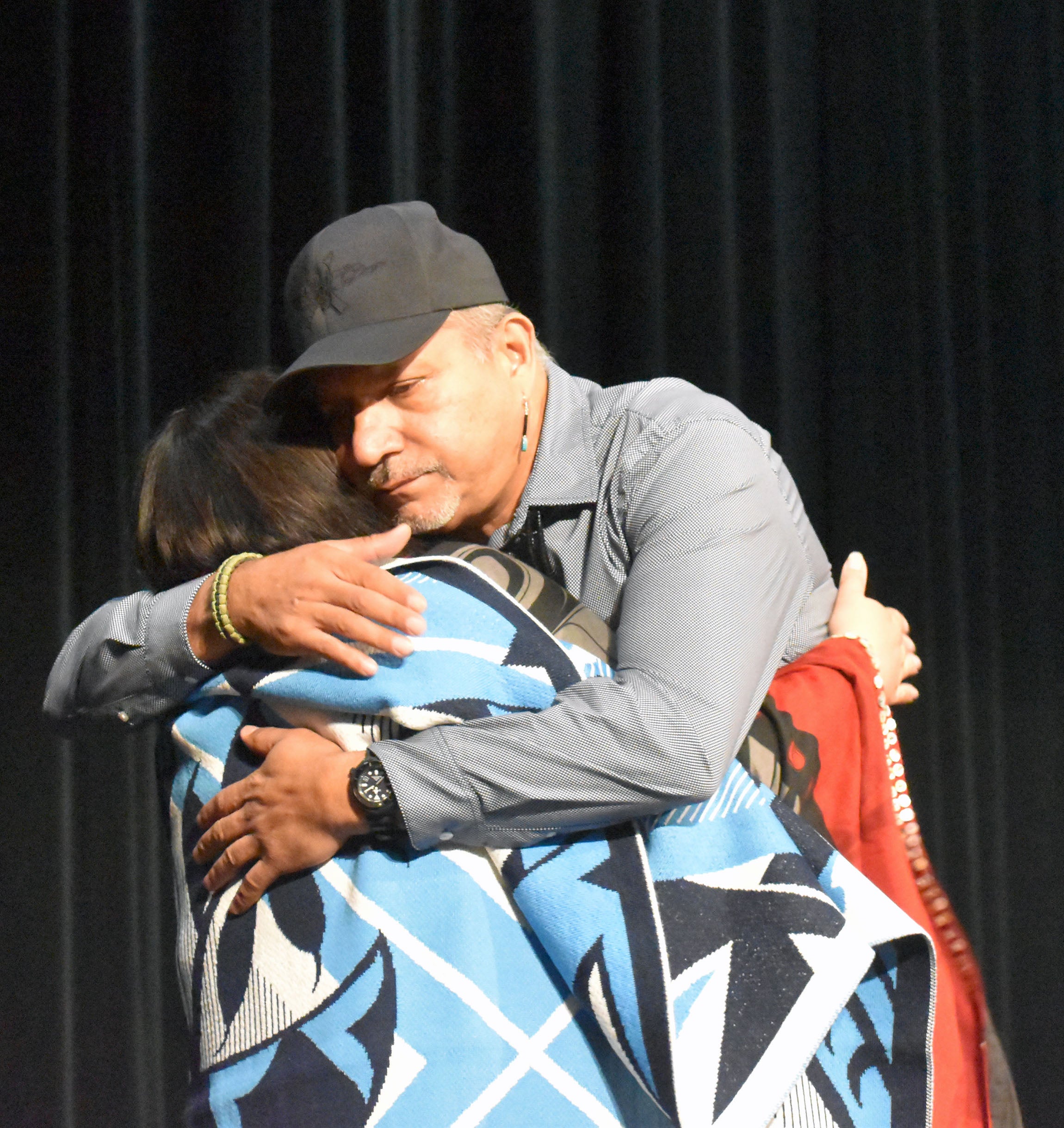

About two weeks after the reunion, the Fond du Lac tribe hosted a celebration Thursday to mark the return of those lands.

Evers and Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz attended the ceremony, as well as Wisconsin U.S. Sen. Tammy Baldwin.

They acknowledged the land transfer doesn’t make up for the loss of culture, identity, or generations of historical trauma. Evers said the state shares responsibility with the federal government for recognizing the pain inflicted on tribal communities then and now.

“This is your land. It has always been your land,” Evers said. “We’re happy to see this important path to justice move forward.”

The restoration of the tribe’s burial grounds shows tribal families and communities have the right to care for the sites of their ancestors, said Bryan Newland, assistant secretary for Indian Affairs within the U.S. Department of Interior. Last year, the department took steps to make it easier to restore tribal lands to remedy federal policies dating back nearly 200 years that forced tribes from their homes.

“Your grit, your determination, your relentless effort to seek justice for your ancestors has begun to mend the tears in the fabric of your community made a century ago,” Newland said.

The transfer of burial sites included work among multiple governments, as well as St. Francis Xavier Church. The 1.6-acre exchange includes a 0.2-acre plot at Wisconsin Point and around 1.4 acres near St. Francis Cemetery in Superior, where the remains of tribal members were reburied. The church had already deeded lands to the tribe prior to the community celebration, and the Rev. James Tobolski said he hoped their return brings deeper reconciliation.

Superior City Council president Jenny Van Sickle, an Alaskan Native who initiated the effort to return tribal lands and received council support last year, told Wisconsin Public Radio it’s important to humanize places that can get lost in textbooks — if they’re included at all.

“They’re real people with stories,” Van Sickle said. “Native perspective, native voices are not optional, and there’s a lot of work ahead.

Osaugie descendant Bob Miller said at the ceremony he wished his grandma was still alive to witness the return of those lands.

“She told me that if we ever got part of the Point back, she would be the first one to move out there,” said Miller.

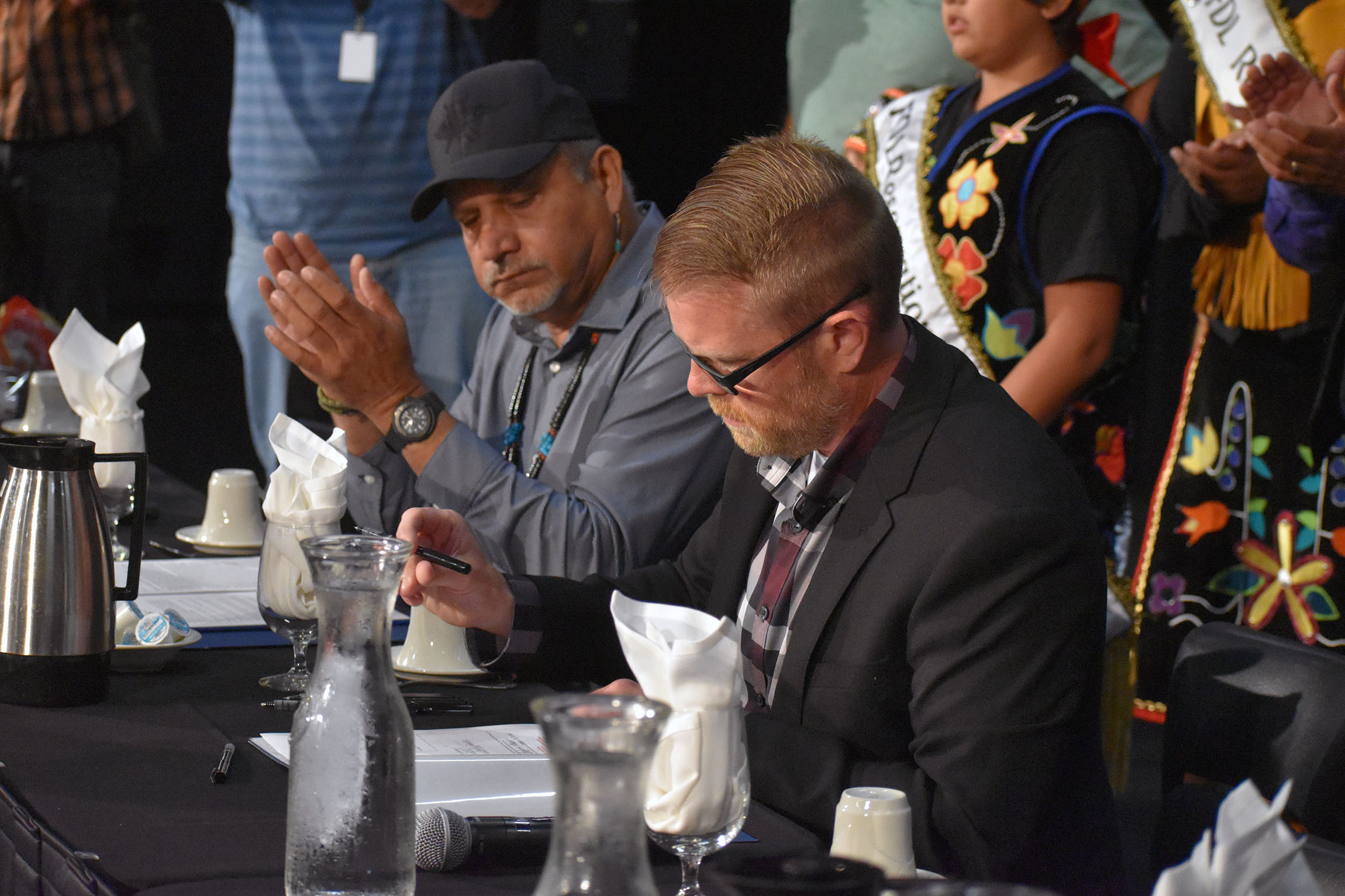

Minutes before signing over the lands Thursday, Superior Mayor Jim Paine called it the most important act he’s ever done. Fond du Lac Tribal Chairman Kevin Dupuis looked on and applauded as Paine finalized the return of their burial sites.

The tribe is now expected to work toward placing the land in federal trust for the Fond du Lac to oversee. The small lot will still be open to the public. Offerings of tobacco, copper and even stuffed animals have been left at the burial site in honor of those once laid to rest there. Speaking after the ceremony, Dupuis said the work ahead may include a monument to replace pillars that currently mark the site. He said the future of the burial grounds should be determined collectively by the tribe and families of Chief Osaugie.

Dupuis searched for words to describe the feeling behind the moment, saying he felt he should be at those burial grounds.

“Just take a public cemetery that exists today, (imagine if) somebody comes in and picks the people up and moves them somewhere else,” said Dupuis. “It’s the thing with all belief systems that when people are put into the ground … that’s their final resting spot. None of us have the right to do that — no matter what.”

At Thursday’s event, Colleen Aird, who marked her 99th birthday days earlier, called it a double celebration.

“I never thought this day would ever come,” Aird said.

Nelson said she’s glad they could both be there to witness the historic moment.

“It’s a good day,” she said, repeating the phrase in Ojibwe. “Mino-giizhigad.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to reflect Colleen Aird is 99 years old.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.