Half a century ago, a convicted Florida man named Clarence Gideon wrote a handwritten letter to the U.S. Supreme Court. He argued that he was denied justice because he couldn’t afford a lawyer and should have been given one at his trial.

This article launches our series on the 50th anniversary of Gideon v. Wainwright, the decision that led to the right to counsel for low-income people accused of crimes.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Fresh out of law school and on his first day in private practice, Superior attorney Toby Marcovich was appointed to take a case of a man who couldn’t afford a lawyer. Marcovich demanded a preliminary hearing. The judge didn’t like that and threatened to cite him for contempt of court. This was 1954, nine years before the Gideon decision.

“We got paid nothing to do this but my client, shortly after deer season opened, brought me a big bag of venison,” said Marcovich. “That was my first experience of being appointed counsel. And it was almost my last.”

The judge didn’t hold Marcovich in contempt.

While judges in Wisconsin generally did appoint a lawyer for people who couldn’t afford one, Douglas County Public Defender J. Patrick O’Neill says it was often long after a person had been charged and interrogated, and not long before the trial began.

“If [a judge] felt the person deserved representation, he’d say ‘Bailiff! Go find a lawyer,’’ says O’Neill. “Bailiff would go out, wander the halls of the courthouse, maybe go down to the local coffee shop. When he found a guy he recognized as a lawyer, [he’d say] ‘The judge wants you right now’, drag him into court; judge would say ‘Mr. Lawyer, here’s your new client.’”

O’Neill says more than half of the people accused of crimes in Douglas County qualify for a court-appointed attorney. Before Gideon, whether a judge would appoint representation in most states was hit or miss.

Walter Dickey, who has taught at the University of Wisconsin School of Law since 1976, says defense attorneys just weren’t commonplace.

“It’s not just that there was no right,” says Dickey. “There was no culture in which criminal defendants were uniformly having an expectation of representation.”

The Constitution Project’s criminal justice policy counsel Liz Fasse says the lack of legal expertise aside, a courtroom is a pretty intimidating place for a person without an attorney.

“It meant that they were facing the great resources of the state against them,” says Fasse – resources including police, investigators, prosecuting attorneys, and the judge.

Before Gideon, Fasse says many people were found guilty of crimes they didn’t commit.

“Unfortunately, we don’t know how much injustice was done,” she says. “According to the National Registry of Exonerations, we now are at over 1,200 individuals who have been exonerated for crimes they did not commit. Unfortunately, that’s probably just the tip of the iceberg.”

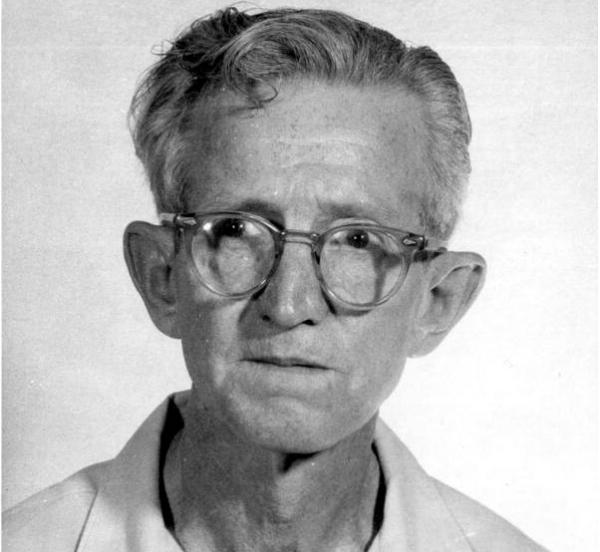

On June 3, 1961, Clarence Gideon was convicted of stealing wine and change from a vending machine in a Florida pool hall. He asked for but was denied an attorney. Sentenced to five years in prison, the man with an eighth grade education wrote a letter to the U.S. Supreme Court, asking for a new trial.

In an archival interview, Gideon said he didn’t need a law degree to write that letter.

“I thought actually that was a law,” he said. “I thought that was a constitutional right and didn’t know no different. And a man with money can hire a lawyer to represent him. He’d get a better chance in a trial than I would get without an attorney. To me, that was just common sense.”

On March 18, 1963, the Court ruled unanimously that Gideon’s constitutional rights were violated and that everyone has the right to counsel. Gideon was found innocent in his second trial.

Still practicing law in Superior, Toby Marcovich says Gideon changed everything.

“We were getting probably too many assigned cases as private attorneys before the public defenders system came into effect,” he says. “But after Gideon, it was overwhelming.”

State legislatures funded public defender programs and people who couldn’t afford an attorney got one.

“Even as a prosecutor I felt that it was important for defendants to have their rights preserved,” says Marcovich. “There was some bad stuff going on, on occasions: people actually being deprived of rights, given bad information, sometimes maybe deliberately.”

On March 18, 1963, that changed.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.