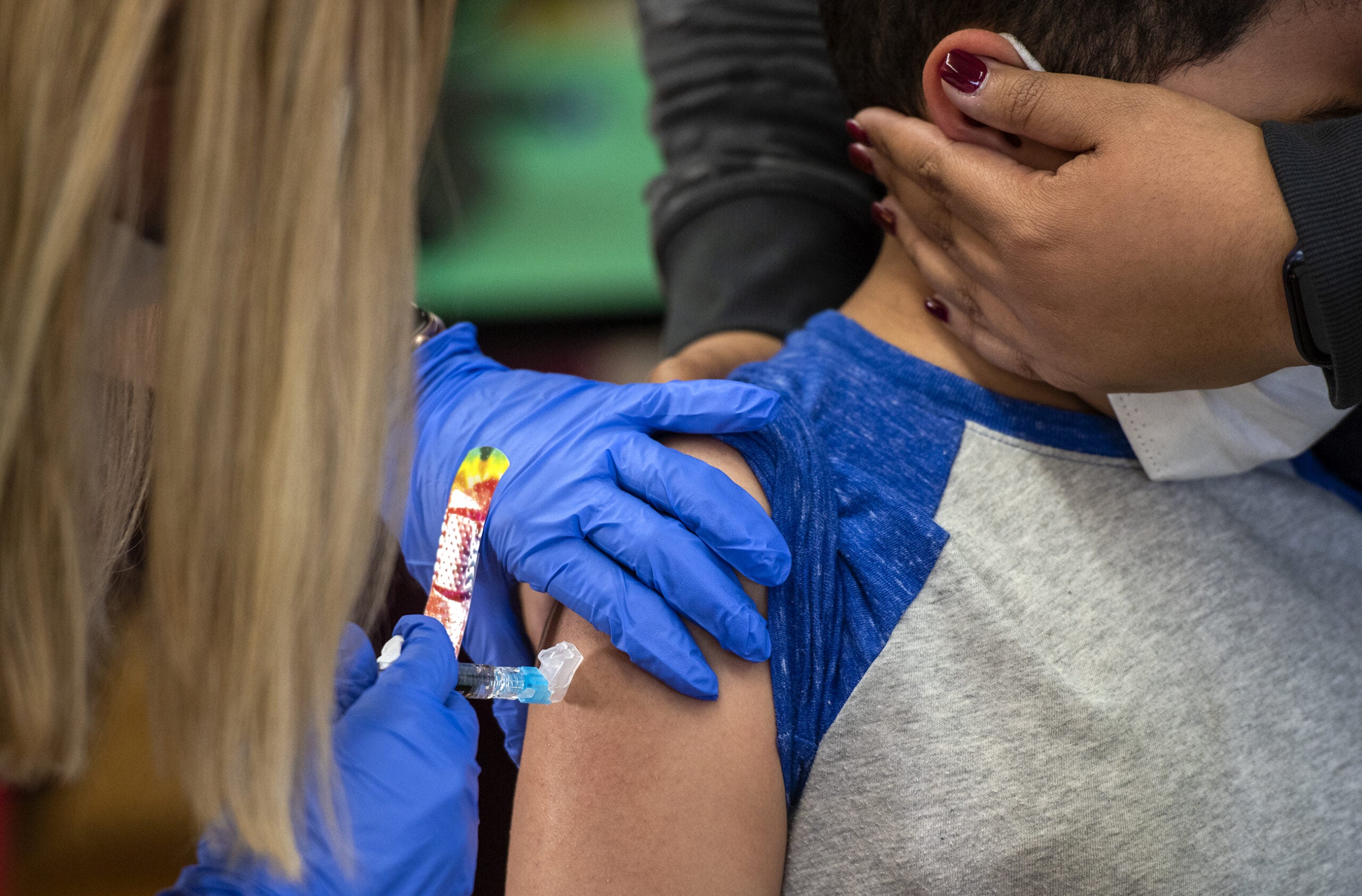

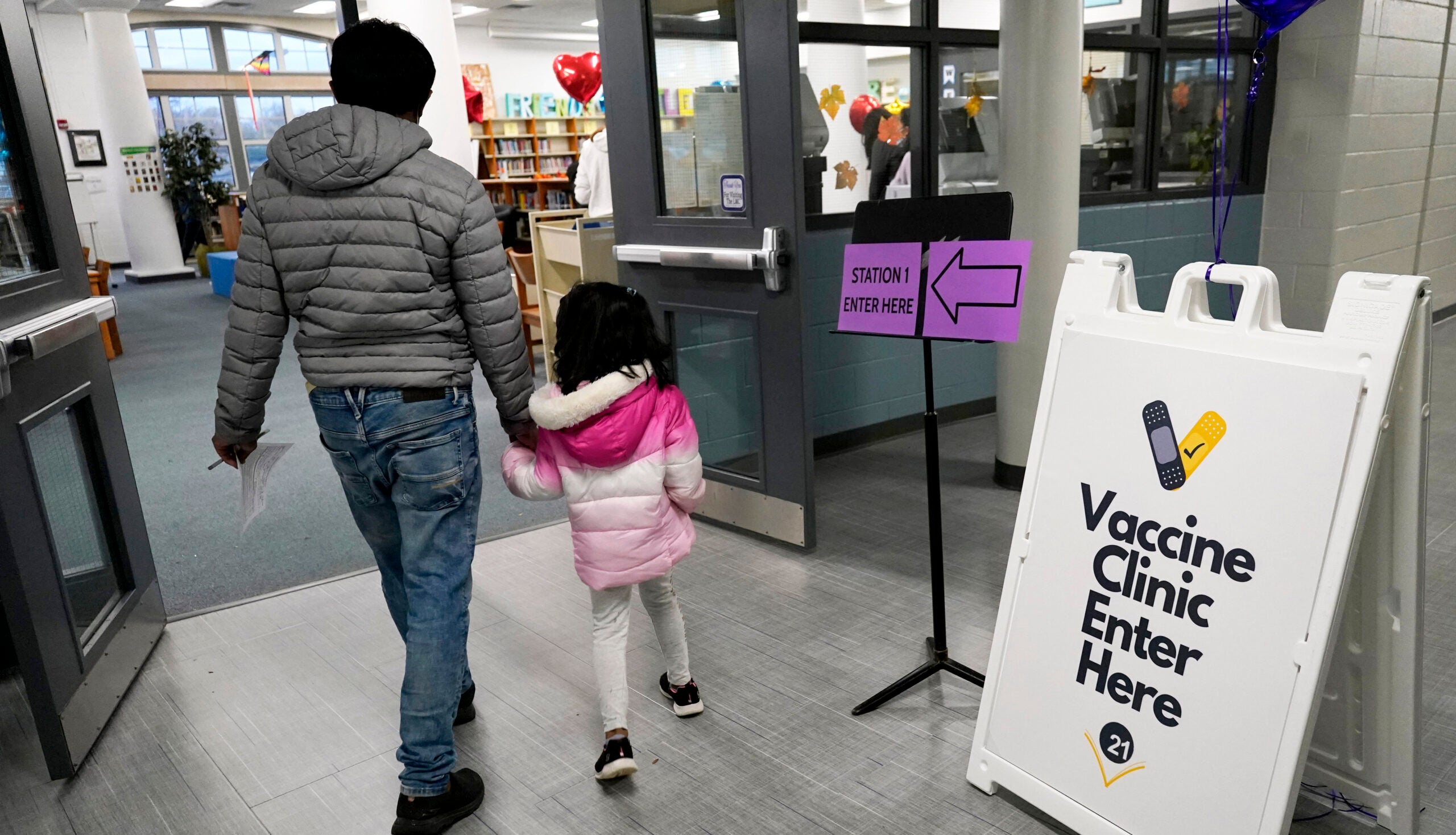

With just over a month since the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine received emergency authorization for kids ages 5 to 11, the Wisconsin Department of Health Services says about 87,000 Wisconsin children have gotten at least one dose of the two-dose series, out of about 500,000 children in the state in that age group.

Some families booked an appointment or showed up at a clinic the moment the shots were available. They said getting shots for their kids would keep more vulnerable family members safe, or recounted frightening hospital experiences when kids had gotten COVID-19 earlier in the pandemic.

Other families, though, are waiting. Even though the parents happily rolled up their sleeves for the vaccine when they were eligible, when it comes to their kids, they’re weighing the risks differently.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“I was in the category of Johnson and Johnson vaccine recipients who was kind of just waiting for 10 days to see if I was going to get a blood clot and die, and it was really scary,” said Beth Redeker. “I could live with the choice that I made for myself, but if I did something that hurt my child, I felt like there would be so much more guilt — so I just wanted to wait and see.”

Redeker was one of several parents who responded to a request from WPR’s WHYsconsin asking what made vaccinated parents hesitant to vaccinate their children. According to data released by the Kaiser Family Foundation right before the Pfizer vaccine was approved for younger children, 27 percent of parents across the country were eager to get their 5 to 11-year-old child vaccinated right away, one third wanted to wait and see how the vaccine was working, and 30 percent said they definitely wouldn’t vaccinate their children.

Redeker’s husband works in agriculture, and she teaches adult education at a technical college. She said they were eligible early for the COVID-19 vaccine because of their work, and they signed up to get it immediately, eager to avoid missing work or trying to manage a quarantine with three kids ages 5 and under. She and her 5-year-old son got COVID-19 in October 2020, and then he contracted it again in November 2021.

“When it came to protecting my son, I mean, he’d already had COVID once and I didn’t even know he had it,” she said. “My son has proven healthy the first time, and so I just felt like, I wanted to wait a bit (to vaccinate).”

Redeker said she’s been keeping up with the scientific and health research on COVID-19, and even participated in a research study for COVID-positive breastfeeding moms when she had the virus last October.

Children’s risk of contracting a severe case of COVID-19 is much lower than that of adults, though they’ve been making up an increasing share of the Wisconsinites who have contracted COVID-19 and been hospitalized, as more vulnerable adults have been getting vaccinated. According to DHS data, as of Nov. 28, 146,443 people under 18 had tested positive for COVID-19 since the beginning of the pandemic.

Children with preexisting conditions like asthma, autoimmune conditions and even behavioral conditions that make it harder for them to mask consistently or hew to other COVID-19 precautions are at higher risk for contracting and getting seriously ill, or even dying, from COVID-19.

James, who asked that WPR not use his last name for fear of reprisal, said his family’s lack of preexisting conditions was a factor in their decision to wait to get their kids, ages 12 and 8, vaccinated — as was the fact that their school district, Madison Metropolitan, has had other strong preventive measures in place like masking and teacher vaccination.

“That’s played a role, in that we really don’t have any issues,” he said.

Dr. Laura Cassidy, director of epidemiology at the Medical College of Wisconsin, said families shouldn’t bank on a lack of preexisting conditions when they decide whether to vaccinate their kids.

“With children, sometimes we don’t know what conditions they may have — some children aren’t diagnosed with asthma as early as others, and sometimes we learn along the way that a child may have a condition that has not been diagnosed or we’re not aware of, so that, you can’t consider as protecting them,” she said.

She added that some preexisting conditions may make it six times more likely that a child is hospitalized with COVID-19, but that doesn’t mean the risk to kids without those conditions is zero.

Redeker said that if data comes out that the new omicron variant puts kids at higher risk for a severe case of COVID-19, that would tip the balance for her to get her 5-year-old vaccinated.

Redeker added that her decision is likely influenced by her environment. The family lives in Brandon, Wisconsin, where mask-wearing has been sparse throughout the pandemic, and vaccine uptake is lower than in places like Dane or Door counties. She recently took a trip to San Francisco, and was amazed by how consistently everyone was wearing masks.

“Everybody was just like, it’s what we do,” she said. “I think that it’s very community-based, that where you live kind of increases the guilt. I think if I lived in a bigger city, I’d probably be more willing or more open to vaccinating my 5-year-old, because of the guilt or the pressure from the community.”

James, in Madison, said he wants to see a couple of years of data on the long-term effects of the vaccine before he’s ready to get the shot for his kids.

“I think just time alone would do it, at least in our case,” he said. “It’s just, especially with young, growing bodies, there’s nobody on the planet that can tell us that it’s going to be safe long-term.”

It’s a concern Cassidy recognizes, but said is outweighed by the risks of COVID-19.

“I’m not sure we have the luxury of waiting one or two years,” she said. “The more data we have, the better, but the more people who are unvaccinated, then the easier it spreads, mutates and can become worse.”

Other concerns that parents, both those interviewed and those who wrote to WHYsconsin, described included frustration that it’s hard to get good information about more severe side effects, and concerns that the Pfizer vaccine, the only shot approved for children so far, has slightly lower efficacy than the Moderna vaccine.

When it comes to side effects, the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, or VAERS, is simply a list of self-reported incidents that aren’t verified by a medical professional or otherwise checked. Cassidy said that she looks to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Johns Hopkins for accurate information about vaccine side effects, which at worst and in very rare cases have included a severe allergic reaction – a risk, though very minimal, for most vaccines – and myocarditis, or inflammation of the heart muscle. She also said that it’s highly unlikely there would be a verified case of a more extreme side effect without medical institutions, or the public, hearing about it.

“Millions of people have been vaccinated without many side effects, so when there is one, it tends to be magnified, and everyone hears about it,” she said.

When it comes to vaccine efficacy, she emphasized that all the approved vaccines have been shown to be highly effective both in clinical trials and in the real world at preventing severe disease. For both mRNA vaccines, the efficacy is 84 percent or higher after 6 months, well above the Food and Drug Administration approval threshold of 50 percent efficacy, while the Johnson and Johnson vaccine had 72 percent efficacy, which is bumped up to 94 percent with a booster shot.

“Any vaccine is better than no vaccine,” Cassidy said. “Waiting for one, you’re just increasing your risk, and these vaccines all offer such good protection – Pfizer offers really good protection, and you know, maybe you get a booster later, but I would rather be protected now, going into the winter season where the rates are going up and new variants are out.”

Both Redeker and James said that while protecting other people around them — in particular, vulnerable elderly family members — was a major reason they got their own vaccinations early, it doesn’t feel like as compelling a reason when adults who want the vaccine have been able to get it for months.

“I think the kids have had a lot of this virus protection and ‘Stop the Spread’ put on them at such a young age, and I feel like, it’s up to adults to stop the spread, if they’re the ones who are vulnerable, to make the good choices for themselves,” Redeker said. “When it comes to my child, I just feel like, is it really the children’s job to protect the adults around them? Or should it be the adults’ job to protect the children?”