One day in the mid-1990s, Kate Nicholson was sitting at her desk working at the United States Department of Justice when she felt a burning sensation in her back. Shortly after, her body seized and she fell to the floor.

For 20 years after that, she couldn’t sit, stand or walk for more than short distances with a walker.

Nicholson, a civil rights attorney, credits proper pain management treatment for learning to adapt to her condition and allowing her to continue to work and function despite the pain.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“Turns out that it was related to a surgical injury where they had cut a major nerve plexus in my spinal cord,” she said. “And when the nerves repaired, scar tissue … formed and really damaged things for me.”

After trying dozens of other ways to treat her pain, Nicholson went on prescription opioids, along with other integrated treatments, until advances in medicine improved her health and she was able to stop taking the drugs.

Yet, many chronic pain sufferers today face a different picture, she said.

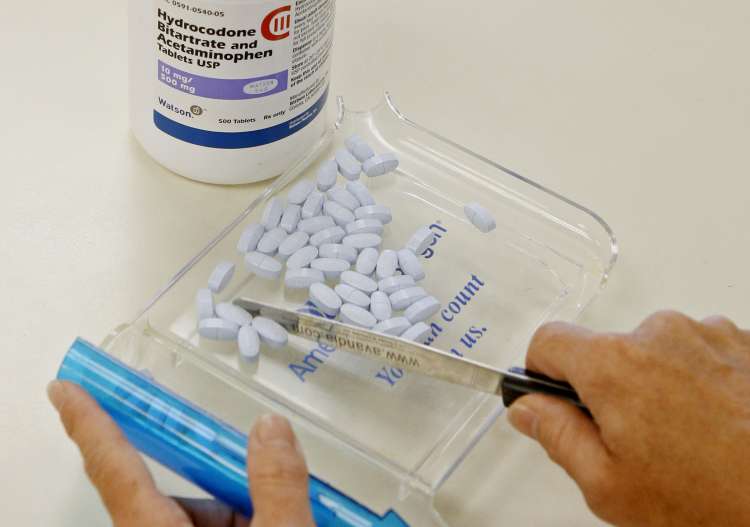

In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued recommendations for physicians on prescribing opioids for chronic pain in response to rising rates of addiction and overdose deaths, recommending that opioids be used at the lowest appropriate dose for the shortest period of time.

The interpretation of those guidelines was extreme, Nicholson said, and has led to some physicians underprescribing and taking patients off of opioids too quickly.

“(Opioids) were certainly too liberally prescribed for a long time for all kinds of pain,” Nicholson said. “But the corrective right now, we’ve gone sort of from one really broad pendulum swing to another. And it’s claiming victims on both sides of that swing.“

Opioids’ place in medicine has shifted dramatically since the 1990s when they were often broadly prescribed and considered the standard in chronic pain treatment.

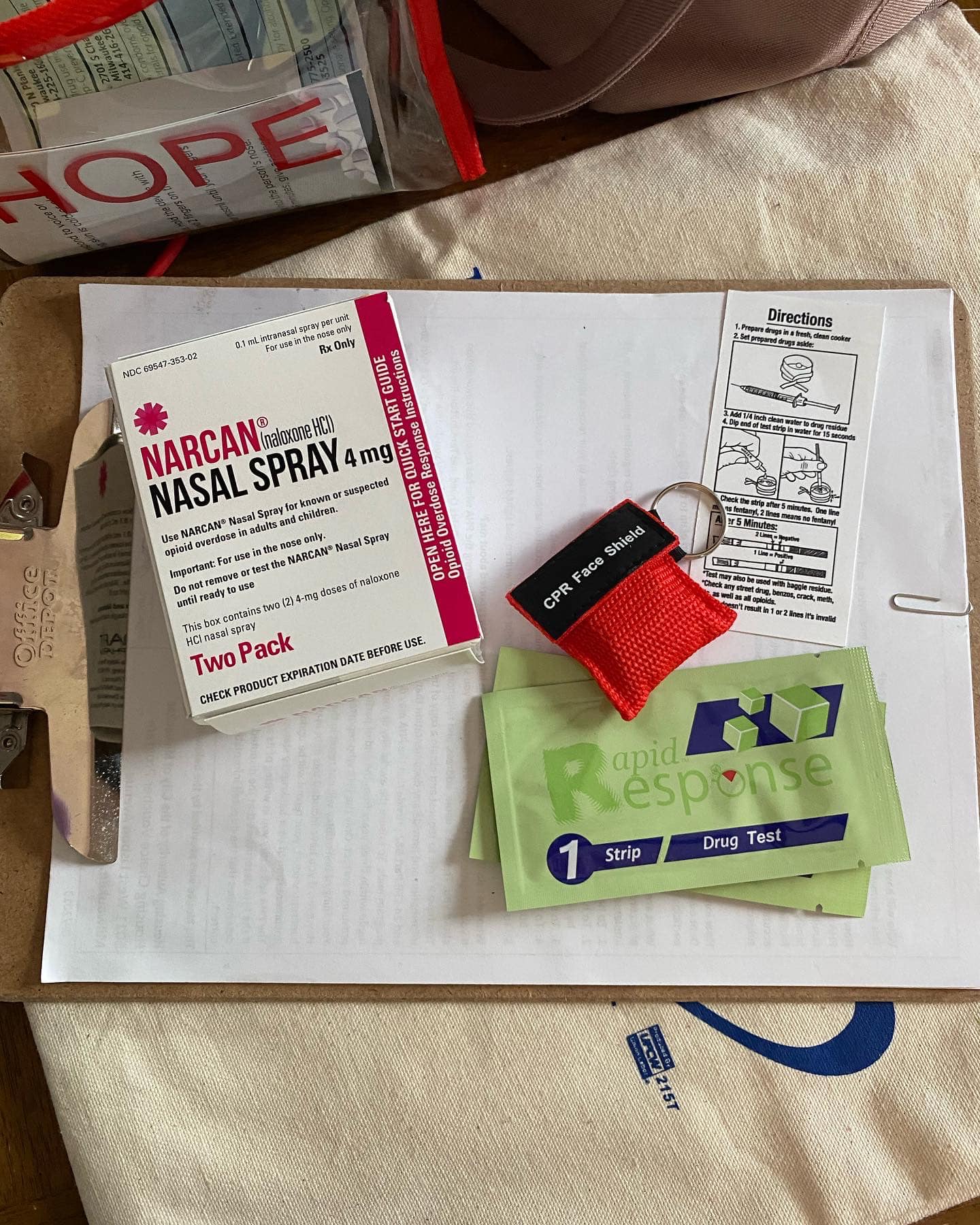

Today’s narrative has taken a darker turn. Opioid-related addiction and overdose deaths have been climbing for years. In 2017, opioids were involved in 47,600 deaths, in the United States, according to the CDC.

But those numbers are part of a complicated story. Synthetic opioids, like fentanyl, are the main driver of drug overdose deaths, making up more than 28,000 of opioid-related deaths in 2017.

Opioid prescribing has also been on the decline since 2010 and the number of prescriptions filled at retail pharmacies is at a 15-year low, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

But Nicholson said the effects of the crackdown have been chilling and have created a level of unintended oversight.

“Much of what is in the CDC’s guidelines is quite well accepted by everyone,” she said. “They were guidelines issued for primary-care physicians, not for specialists … but there were a few provisions in those guidelines that were … turned into laws and mandatory policies.”

Dr. Alaa Abd-Elsayed, medical director for pain services at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health, agrees that opioid prescribing went from one extreme to the other.

“(Doctors) started aggressively weaning down opioids very quick to be compliant with the guidelines and stop opioids,” he said. “And in my opinion it doesn’t work this way.”

That approach leaves an unnecessary gap in a patient’s care, he said.

“You have to provide alternatives to treat the pain and then slowly and gradually wean down the opioids so patients don’t get withdrawal,” Abd-Elsayed said. “Weaning down the medications very quick can be very unpleasant.”

Abd-Elsayed prefers to try alternative treatments, such as physical therapy, yoga or psychology and over-the-counter medications like tylenol and ibuprofen before turning to opioids.

However, there are situations where opioids are an important part of treatment, though they must be monitored and tailored to the patient, he said. For some patients, a low dose for a short amount of time is necessary to even begin physical therapy, he said, and for others, like cancer or palliative care patients, opioids are needed.

“Sometimes we start opioids for certain duration of time to achieve certain goals and then we stop them,” he said. “People think you start opioids and the patient has to be on them forever. That’s not true.“

Opioids are very effective at treating chronic secondary pain over a short period of time, but there is little evidence that opioids are effective as a long-term solution to chronic pain, said Dr. Matt Hearing, a neuroscientist at Marquette University College of Health Sciences.

Over time, patients develop tolerance to the drug so they have to continue to take more and more for it to be effective, he said, and there is increasing evidence that having chronic pain can change parts of the brain’s reward system that could make people more susceptible to developing addiction.

For example, with chronic back pain, opioids will diminish the pain, but they won’t address the root of the pain, he said.

“People are given pain medications to dull the pain, but they aren’t provided with alternative means like physical therapy,” Hearing said. “Once you have this initial insult that causes you pain over a long period of time, that change in your body … what you’re left with, is something different, so you need to find a way to restore or rebuild.”

The realization that opioids aren’t a good long-term solution to chronic pain have left both patients and physicians in a difficult space.

“I think it’s important to understand or get rid of this kind of negative stigma that you know that it’s their fault,” Hearing said. “It’s kind of been pushed upon them in part because you know it was deemed the proper treatment at that time and now they’ve been put in a state of change.”

Nicholson said there has always been a stigma attached to pain, but the current climate has inflamed it.

“Pain patients are seen as drug seekers and liabilities,” she said. “What’s happening with physicians, it’s not like they want to drop their patients, but they’re concerned about liability. And and in some senses pain patients are also seen as further residue of the shame of overprescribing and the deaths that we see.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.