Evelyn Gonzalez, 3, hopped on her dad’s lap as her parents were interviewed for this story, giggling in her favorite yellow pants as she told the Zoom camera her name and age, releasing a squeal through smiling teeth the word that accompanies pictures: “cheeeeese.”

Her parents, Mario and Jennifer Gonzalez, were “surprised in a good way” when they moved to Green Bay six years ago. Mario, 32, is of Puerto Rican descent and from Chicago; Jennifer is 39, white and from Manitowoc County.

The Gonzalezes say Green Bay offers a perfect balance of small-town charm and citywide amenities. And it’s inclusive, they added, a factor that will become increasingly significant for children like Evelyn and another baby girl due in April.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“Our children will be immersed in the diversity, where they will fit in, especially because they are mixed race,” Jennifer said. “They’ll see other kids with their complexion and darker features. Right now, it’s fun watching Evelyn wave at everyone she meets. She doesn’t see race, yet.”

In Green Bay, Evelyn gets exposed to other races and ethnicities, babbles in Spanish and English, and, because Mario volunteers with the Miracle League of Green Bay, she also befriends youths with disabilities, allowing her prism of acceptance to grow.

“It’s exciting to see that the demographics are changing, because it helps reinforce that Evelyn can be exposed to people of all walks of life,” Mario said. “That’s extremely important to us.”

The family is among the contributors to increasing racial and ethnic diversity in northeast Wisconsin, where the number of Black, Asian, Native American, multiracial and Hispanic people increased 57 percent over the past decade, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

The population growth in Brown, Outagamie and Winnebago counties was most pronounced in the larger cities, but it also played out in smaller communities as job opportunities, family connections and quality of life considerations attracted new residents to the region.

Diversity reinforces diversity, as the Gonzalezes attest. It’s simple math, experts said. When families of color move to this region and find it comfortable and welcoming, other relatives often join, and other people from elsewhere looking for a higher quality of life pack up and follow suit.

USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin spoke to urban sociologists, housing experts, lifelong dairy producers, community organizers, teachers and others to learn more about the reasons behind the region’s diversity boom.

Here are five key takeaways:

Hispanics are the region’s largest minority group

Maria Plascencia, a member of the Casa ALBA Melanie community service organization in Green Bay, moved to the city from Anaheim, California, 14 years ago, hoping to rinse herself of the impersonal bustle and fast pace of Orange County life. She found the relative quiet refreshing, and Green Bay, despite its harsh winters, beautiful.

Plus, the traffic in California was horrible.

“Coming to a place that was green, had that quietness … it’s a nicer and more peaceful place,” Plascencia said. “There’s still a lot of movement, which is good, and the police department does a good job, in my mind, of keeping the community safe.”

Hispanic and Latino residents of communities along the Interstate 41 corridor between Oshkosh and Green Bay increased by 46 percent between 2010 and 2020.

As the largest minority group in the region, Hispanic residents now make up 18 percent of Green Bay’s population, 8 percent of Appleton’s population (with an over 50 percent increase since 2010), and 5 percent of Oshkosh’s population (with a 68 percent increase since 2010).

The growing number of Hispanic and Latino people in northeast Wisconsin outpaced Hispanic growth nationwide in the last 10 years, but lags the multigenerational growth that has built large Hispanic communities in other parts of the country, according to Ray Hutchison, professor of sociology and anthropology at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay.

The uptick in northeast Wisconsin is fairly new. The three-county region had just 15,000 Hispanic residents in 2000, about 60 percent of whom lived in Brown County. By 2010, there were 30,000 Hispanic residents and by 2020 there were more than 45,000.

City populations are rising, but fewer white people are living there

U.S. Census data show a decline in the white populations in Appleton, Green Bay and Oshkosh, even as the overall population grew slightly in those cities.

Suburbs and more rural areas near those cities experienced substantial population growth in the past decade, including population jumps of 20 percent or more in fast-growing communities like Hobart and Lawrence in Brown County, Greenville in Outagamie County and Harrison in Calumet County. White people accounted for three-fourths of the growth in those communities.

The change has been driven largely by renters and first-time homeowners seeking larger, newer homes, most of which are being built in suburbs and semi-rural areas surrounding the cities.

Baby boomers’ retirements also play a role; downsizing often means moving from the metropolitan areas that once were convenient for their children’s upbringing to suburban housing developments.

Dave Van De Hey, a lifelong farmer at New Horizons Dairy Inc. in Wrightstown, said that he’s watched for years the rapid pace of farmlands being converted to housing projects.

Nearby Lawrence, for example, has grown by nearly 50 percent, with a 40 percent increase in residents who are white.

“The town of Lawrence is expanding so fast that, as soon as they put the roads up and build the houses, there’s people living in the homes,” Van De Hey said.

Meanwhile, the white population is shrinking in the cities. Green Bay had 12 percent fewer white people in 2020 than it did in 2010. Appleton has 5 percent fewer white people and in Oshkosh the white population shrank by 7 percent.

In that period, new residents of different races and ethnicities moved in, resulting in small increases in each city’s total population.

Multiracial people tripled in three counties

By far the largest shift documented by the 2020 census was the growth of those who reported that their ancestry includes two or more races. Their numbers more than tripled in Brown, Outagamie and Winnebago counties.

Nearly 40,000 people, or 6 percent of the three counties’ total population, reported being multiracial on the 2020 U.S. Census.

“That’s a huge change,” said Andrea Huggenvik, social justice program specialist for YWCA Greater Green Bay. “It’s entirely possible that it’s due to interracial coupling, but I also think that people are just more willing and able to think about their own identities in a more complex kind of way.”

While hearts and minds are changing for many in the region, improvements in data collection also played a role in the increase, according to David Egan-Robertson, demographer at the Applied Population Laboratory at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Egan-Robertson explained that 2020’s census allowed residents who took the survey online to fill in substantially more about their ancestry than was possible in the past, providing a much more accurate reflection of the country.

Fast-growing minority youth populations

Jennifer Gonzalez remembers a time in recent memory when a mother raised concern that Green Bay schools were becoming “too diverse.” The comment took her aback.

When the Gonzalezes’ children go to school, Jennifer worries that their daughters could face that attitude, but she’s mostly looking at the community in a positive light.

“I’m excited for them to be part of a diverse culture, and be part of a diversity at the school,” Jennifer said.

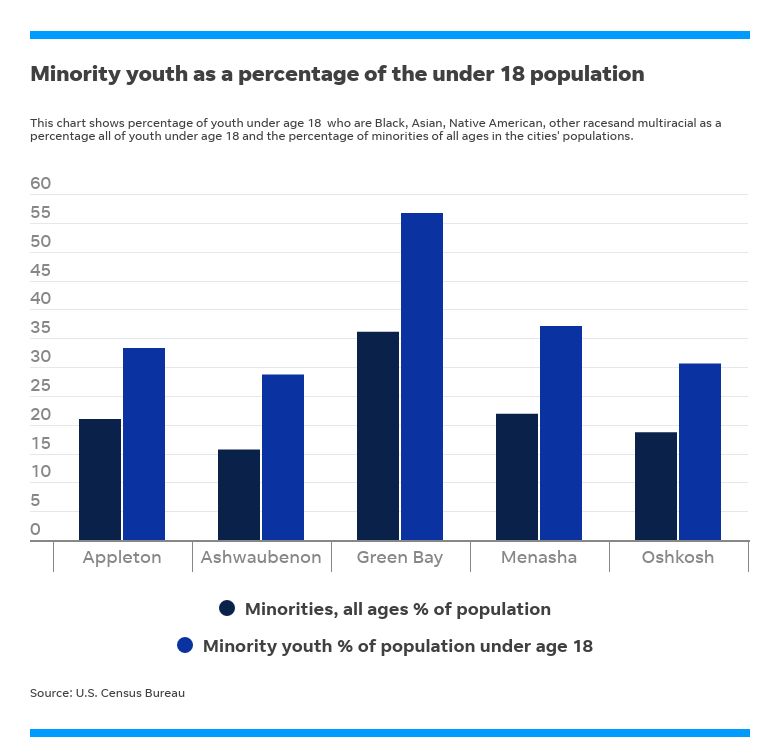

In Green Bay, Hispanic, Black, multiracial and Asian children made up the majority of the district’s students for the first time in 2015, and now account for 58 percent of enrolled students.

In Outagamie and Winnebago counties, their numbers haven’t reached the level of Green Bay, but are steadily climbing. Still, in Appleton, Menasha and Oshkosh, minorities make up between 30 percent to 35 percent of the under-18 population.

But even as classroom demographics change, districts have struggled to hire and retain staff that reflect their schools’ diversity.

As a first-generation child of Mexican parents, Cynthia Contreras, a bilingual teacher at Sullivan Elementary School in Green Bay, knows how important it is for her students to see people like her in leadership roles.

“For them, being able to identify themselves with me or any other teacher they see in the school has a big impact,” Contreras said. “We look like our students. Our language is very important. Knowing they can communicate in both languages makes students feel more comfortable and connected with specific adults.”

Rural populations fell in most areas

Dan Brick, a partner with his father at Brickstead Dairy, remembers a time, around 20 years ago, when neighbors would roll up their sleeves and do work around his farm. It hasn’t been that way in quite some time.

Wisconsin’s family farms have gone out of business in record numbers — between 2014 and 2019 about 500 farms a year were shutting down — leaving fewer neighbors to help neighbors.

At the same time, many of the children who grew up on those farms aren’t interested in agriculture or living in rural communities and are leaving for opportunities in more urban places.

“I don’t have any other neighbors anymore,” Brick said. “I don’t think anybody really wants to work here anymore.”

Census data underscores that trend, showing population declines in rural towns across northeastern Wisconsin. At the same time, the Hispanic population has grown in many of those towns as workers moved in to fill the labor gap.

Brick, like many Wisconsin farmers, has assisted his employees in moving from cities like Green Bay and Appleton to nearby houses and apartments near the farm, along the border of Brown and Outagamie counties.

Some employees, 10 out of 12 of whom are Hispanic, have been with Brick for about 20 years and are homeowners with children. But lately, newer workers have had to room together because of a scarcity of housing — and they rarely arrive alone.

“Usually, when an employee comes, there’s a family, there are kids involved. It’s a struggle to be able to secure housing,” Brick said. “There’s really, really a lack of housing anywhere.”

As commercial farms buy up more parcels and automatize much of the process, people are seeking jobs more often with food processing plants. Those jobs are in closer proximity to urban settings.

Hutchison, of UW-Green Bay, said mechanization, changes in crop production and other changes have significantly reduced farm jobs since 2000, which contributed to the erosion of the rural population across Wisconsin. People who once might have worked on farms, he said, are more often turning to jobs at urban-centered food processing plants.

Those shifts, coupled with family farm closures and the waning interest of younger generations in wanting to remain in small-town America, have resulted in a diminishing rural population.

“In part, it’s historical, the movement of kids off the family farms. There’s been a decline in family farms and more directly, of younger adults not wanting that lifestyle,” Hutchison said.

Natalie Eilbert is a government watchdog reporter for the Green Bay Press-Gazette. You can reach her at neilbert@gannett.com or view her Twitter profile at @natalie_eilbert.