Michael Witgen’s deep research of Indigenous and early North American history is evident in his 2021 book “Seeing Red: Indigenous Land, American Expansion and the Political Economy of Plunder in North America.”

A finalist for this year’s Pulitzer Prize in History, the book examines colonization of a region now known as the Midwest and was previously known by settlers as the Northwest Territories.

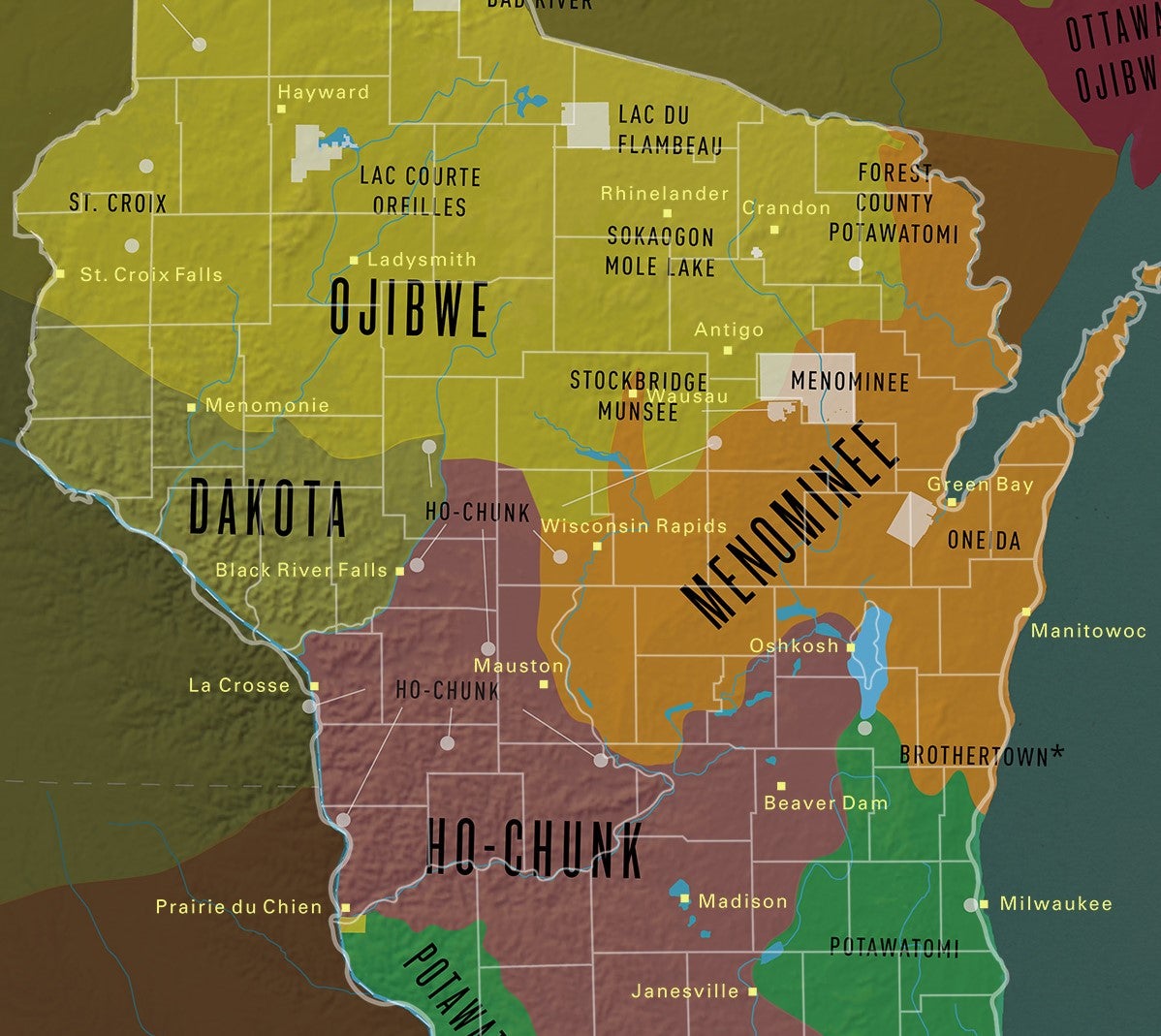

“I think the history of Wisconsin’s colonization is new to most people,” said Witgen, a citizen of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe, in an interview with Wisconsin Public Radio’s “Central Time.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“In grade school, you tend to learn about Indians through the story of the Trail of Tears in the Southeast. You learn that there was a hunger for land, Indians were facing pressure and they were forcibly removed. But that’s not what happened in the Northwest Territories,” he continued.

The U.S. government planned to remove Indigenous people from the Northwest Territories in 1852. After getting wind of the government’s plans, tribal leaders took an arduous journey to Washington, D.C. and negotiated directly with President Millard Fillmore.

“One of my distant relatives was on that trip,” Witgen said. “It’s an amazing example of Ojibwe people fighting to remain in their homelands. That’s part of the story of why Native people in Wisconsin didn’t get removed.”

Witgen, a Columbia University history professor, discussed with “Central Time” how the U.S. government used money circulation and forced treaties to colonize, but not remove, people Indigenous to the region.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Rob Ferrett: A huge part of the book is about how Native Americans reacted to the push to populate states in the Northwest with settlers from out east. What were some of the key points in your research?

Michael Witgen: There are several key points. There wasn’t a lot of population pressure in 1837 for the northern Wisconsin territory, but the U.S. basically tells the Native people that they have to cede it or it’ll be taken from them. And so they do.

The Native peoples are compensated something around 13 cents per acre, which the U.S. can then sell under the Northwest Ordinance for $1 an acre. It made an enormous amount of profit. That property would often enter circulation as private property, undeveloped for 10 or 15 years, where it can then sell for, say, $80 an acre.

So there was this massive transfer of land and wealth from Native people through the federal government to individual settlers in the United States. This process facilitated colonization by creating a monopoly on land sales and making that land really affordable to most people in order to encourage immigration.

RF: How else did the U.S. financially benefit from the forced appropriation and distribution of land?

MW: The federal government took the wealth as well as the land, plundering the resources of the Indigenous population in order to economically develop the state and territory.

People in states like Michigan and Wisconsin quickly discovered that having Indians in place as a colonized subject was way more lucrative than kicking them off and taking over their land.

The federal government forced treaties requiring Indigenous people to cede land in exchange for cash. Usually, however, around 90 percent or more of the payment went to traders or merchants who claimed that Native peoples owed them money from the fur trade.

Merchants would take that money from the government and invest in their own businesses. Many were then hired by the government. They made money by claiming the cash payments as debt and by providing the federal government with provisions that were also part of the annual payment for land sales.

There was a lot of money to be made in not removing the Indians. That cash helped people develop the infrastructure of the businesses in the state economy.

RF: The way English settlers defined land management and ownership did not match up with how other cultures lived. Because of that, the English felt they had a right to the land. This idea feels like it lies at the heart of westward expansion, including what happened in the Northwest territories.

MW: Absolutely. The “doctrine of discovery” is the idea that when Europeans arrived in the Americas, in North America in particular, they’d found a new uninhabited world because it didn’t have recognizable forms of property or private property like you would have in Western Europe.

At some point, settlers had to come to grips with the fact that the land they thought was empty was in fact occupied by Indigenous people. Following through with their plan meant they had to actively work to colonize Native people in their homeland.

RF: What do you make of current land issues related to the descendants of the tribes you write about?

MW: I’m interested in the Land Back movements.

A lot of the land in northern Wisconsin, northern Michigan and the Upper Peninsula was ceded when there wasn’t demand for it. A lot of that land has been passed into public trust for counties or universities. When they were ceded, these lands were sold or given to the U.S. and then used to fund the endowments for land grant universities. Part of the public infrastructure of the U.S. comes from this transfer of land.

Reckoning with that, coming to grips with it and giving the land back if possible is a really interesting recognition of the colonial history of the U.S. while undoing some of its legacies.

RF: Do you want to see wider efforts to share the history that you recount in your book?

MW: Absolutely. I don’t think people realize the extent to which history, particularly in the Midwest, is an Indigenous history. American history is intertwined with Indigenous history in a way that can’t be separated. There’s a connection that Native people have to land that is still here today that precedes America. This is really important for people to think about when tribes exercise treaty rights now.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.