As climate change drives more frequent and intense storms, more nutrients are being flushed off of farm fields into lakes and streams. But a new study finds that extreme storms aren’t immediately triggering harmful algal blooms in Madison’s largest lake.

Phosphorus in manure and fertilizer is the major cause of toxic blooms in Lake Mendota, which is washed off farm fields during extreme rains. Since 1950, average precipitation has increased 17 percent or about 5 inches statewide, according to the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts. The southern two-thirds of Wisconsin has seen the largest increase in precipitation, and that’s only expected to intensify.

In Madison, a four-inch rainfall in one day that used to occur once every five years now happens every other year, according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. That got University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Steve Carpenter wondering whether extreme storms would lead to an increase in toxic blooms.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“I had thought maybe get a rainstorm, get a bloom, but it’s not that simple,” Carpenter said, who is lead author of the study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

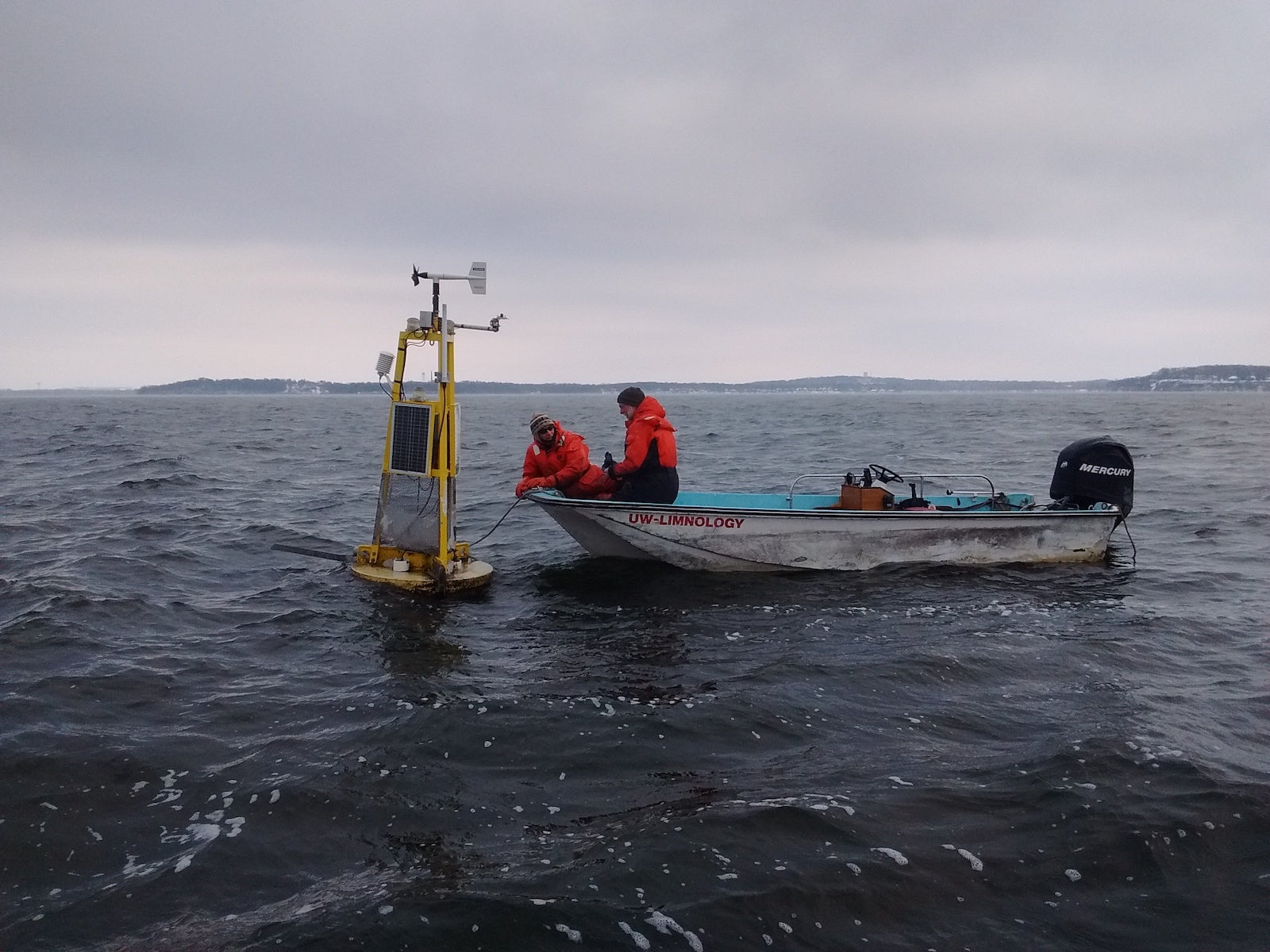

Carpenter, emeritus director of UW-Madison’s Center for Limnology, worked with other researchers to examine data collected from Lake Mendota. He said around three-quarters of all phosphorus pollution stems from extreme storms. While those storms play a large role, they don’t necessarily trigger a bloom right away.

The study found that a mix of conditions must exist for blooms to form, which appear on average anywhere from two weeks to two months after intense rains.

“The blooms happen when … we get a run of warm weather that warms up the lake. Then, eventually, we get a calm day when there’s not much wind to mix it,” Carpenter said. “And the algae just rise up from the sediment like Dracula from the basement and form a bloom on the surface of the water.”

Carpenter said that mix of warm temperatures, calm weather and phosphorus creates an ideal setting for the “monster” to take hold. Once formed, harmful algal blooms can prompt people to avoid recreating in the lake, decrease property values or even make animals and people sick.

He noted another big factor for the formation of blooms is that phosphorus is very “sticky” and can remain in lakes for decades. In fact, toxic blooms have been documented on the lake as far back as the 1880s. Buried in the lake bottom, wind and waves can bring phosphorus that has settled there back to the surface where algae lives, resurrecting the threat of harmful blooms. Another factor that creates a recipe for toxic blooms is fewer zooplankton or tiny animals in the lake.

About 40 years ago, Carpenter said the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources manipulated the lake’s fishery to favor big fish for anglers. That reduced the number of small fish that eat zooplankton and allowed the population of tiny animals to explode. When there’s more zooplankton, they eat up the algae and help keep the lake clear. From 1988 to 2010, the lake enjoyed better water quality.

But Carpenter said that changed with the introduction of the invasive spiny water flea. Oceangoing ships carried the invader that’s native to Europe and Asia in their ballast water, eventually spreading into Lake Mendota.

“The spiny water flea came over around 2010 on a boat and ate all the native water fleas — just wiped them out,” Carpenter said.

Unfortunately, the invasive species didn’t share the same appetite for algae. In addition, fish in the lake are reluctant to feed on the invader due to its spiny tail. With nothing to keep the thorny character in check, the lake has experienced a reduction in water quality.

Carpenter said the changes over time highlight the importance of controlling phosphorus pollution in the lake.

“The lake will eventually cleanse itself,” he said. “It will eventually flush the phosphorus out — if we stop putting it in.”

A report earlier this year identified Dane County among areas where manure and fertilizer are applied at rates beyond what’s recommended by UW-Madison scientists. In parts of the county, the report found there’s too much manure for fields to accept without leading to water pollution unless it’s trucked further away. Carpenter said most phosphorus in Lake Mendota stems from farm runoff into rivers that flow into the lake. According to the study, the Lake Mendota watershed drains around 600 square kilometers of land that’s home to dairy, corn and soybean operations.

Carpenter noted Dane County has begun funding manure digesters for farmers to use while others are experimenting with manure composting.

“Nonetheless, we’ve still got way too much phosphorus in Dane County,” he said. “We need to manage it more rigorously to keep it out of the surface water.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.