Two northwest Wisconsin residents are threatening to sue their town unless elected officials repeal rules governing the operation of large livestock farms.

The town of Eureka in Polk County, Wisconsin, is the latest front in a skirmish over the boundaries of local control of agriculture. The outcome could determine how the owners of large animal operations ensure they won’t jeopardize their neighbors’ safety and quality of life. A court resolution could potentially set a statewide precedent, with sweeping effects to Wisconsin’s $104.8 billion agricultural industry.

“Of course we’re concerned,” said Don Anderson, chair of the town of 1,700. “We would, at this time, plan on getting an attorney.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

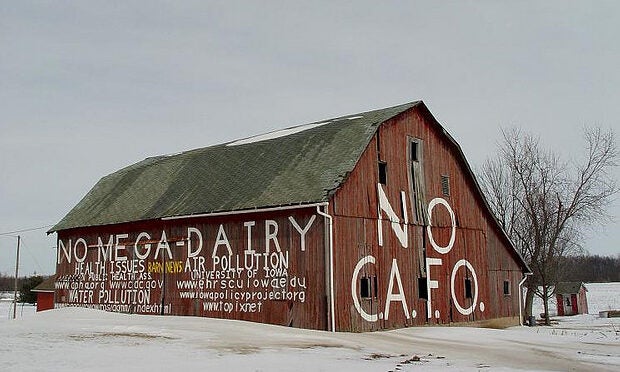

Last year, Eureka fine-tuned its rules regulating large livestock farms, also known as concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs.

Earlier this month, Eureka residents Ben and Jenny Binversie, represented by WMC Litigation Center, sent the town a notice of claim — the precursor to a lawsuit.

Eureka has 120 days to reject the Binversies’ claim, or its nonresponse would be considered as such. Then the matter could proceed to Polk County Circuit Court.

Eureka’s ordinance restricts not where CAFOs may locate, but how they operate, and was based on a model developed by an advisory group comprised of Eureka and neighboring Polk and Burnett County towns.

Ultimately, five towns enacted similar rules, but Laketown, Eureka’s northern neighbor, rescinded its regulations in April following a change in elected leadership.

WMC Litigation Center, the legal arm of Wisconsin’s largest business association, also represented two Laketown farm families who challenged that town’s ordinance before its repeal rendered their lawsuit moot.

One of those families included Michael and the late Joyce Byl and Sara Byl, who are the parents and sister, respectively, of Jenny Binversie. The family operates Northernview Farm, where they milk Holsteins. The town of Eureka sought to intervene in the suit, noting the two towns’ ordinances are “nearly identical.”

Eureka’s ordinance applies to new CAFOs, or smaller facilities with common ownership, that individually or collectively house at least 700 “animal units,” the equivalent of 1,750 swine or 500 dairy cows.

The regulations require applicants to submit plans for preventing infectious diseases, air pollution and odor; managing waste and handling dead animals. They also mandate traffic and property value impact studies, a surety for cleanups and decommissioning, and an annual $1-per-animal-unit permit fee — atop costs to review the application and enforce the terms of the permit.

Eureka’s ordinance goes a step further than others’: Any CAFO outside of the town must obtain the operations permit if the business intends to spread manure within Eureka.

The Binversies’ attorneys argue Wisconsin preempts local authorities from passing regulations that are more stringent than the state’s unless they can prove the requirements are necessary to protect public health or safety.

But even under that exception, which the attorneys say the town doesn’t satisfy, they contend that more restrictive ordinances cannot add new requirements for which there are no state standards. They also argue such ordinances must be approved by the state, a condition they say has not been met.

Additionally, the attorneys claim 18 of Eureka’s ordinance requirements are illegal and federally unconstitutional and injure the Binversies as taxpayers “on an ongoing basis.” While the notice doesn’t explain how the claimants are harmed, it threatens litigation unless Eureka’s leaders repeal the regulations.

Ben Binversie declined to comment, referring all questions to Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce. Scott Rosenow, WMC Litigation Center’s executive director, did not respond to requests for comment.

Town officials have communicated with trial lawyer Andy Marshall, who represented Laketown pro bono and previously pledged his assistance to other area towns with CAFO ordinances. Marshall did not respond to requests for comment.

Should the case be litigated, the Binversies could face challenges in establishing legal standing to proceed with a lawsuit, said Adam Voskuil, staff attorney for the nonprofit law office Midwest Environmental Advocates. He noted that in the claim, the Binversies only said the ordinance harms them as taxpayers, not farmers.

“It seems as though that they are people that don’t necessarily participate in agriculture, really much at all,” he said.

In challenging Laketown’s ordinance, the Byl family claimed its restrictions likewise could harm their interests if they expanded their farm.

“But here there isn’t even that,” Voskuil said. “It’s just simply because we pay taxes, we get to challenge ordinances.”

Lisa Doerr, a Laketown forage farmer who chaired the advisory group, is unsurprised with the latest developments.

“These guys have been basically harassing us for going on five years now,” she said. “Their worst nightmare is to have 1,250 towns in Wisconsin taking control of people’s health and water and the property values.”

While ensuring legislative control requires only persuading 67 Wisconsin senators and Assembly members, reining in the authority of that many towns would prove considerably harder.

“If towns all over Wisconsin can have control over these giant factories that are spreading raw feces all over the neighborhood, it’s the last thing this industry wants,” Doerr said. “Why else would they even care? There isn’t even a CAFO in Eureka.”

Polk and Burnett County residents and property owners were galvanized to regulate large livestock farms in 2019 after a developer proposed an operation, known as Cumberland LLC, that would have housed up to 26,350 pigs — the largest swine CAFO in Wisconsin. The breeding facility would be constructed in the town of Trade Lake in Burnett County.

State officials have rejected the project twice, but the developer submitted a revised application in May for a scaled-down farm, with as many as 19,800 pigs.

Locals formed the advisory group to plug gaps in state livestock laws, which they believe insufficiently protect health, property and quality of life and hogtie local control. For example, the Department of Natural Resources cannot regulate issues unrelated to water quality, including air, noise and vehicle traffic. Meanwhile, Wisconsin’s “right-to-farm” and livestock facility siting laws protect farmers from nuisance claims.

This story is a product of the Mississippi River Basin Ag & Water Desk, an editorially independent reporting network based at the University of Missouri School of Journalism in partnership with Report For America and funded by the Walton Family Foundation. Wisconsin Watch is a member of the network. Sign up for our newsletter to get our news straight to your inbox.