Much has changed in the 170 years since Wisconsin was granted statehood, but the omnipresence of agriculture hasn’t. It’s hard not to notice agriculture around the state, be it in the form of cropland, orchards and vineyards, or the famous dairy farms dotting the landscape.

Wisconsin is practically synonymous with dairy for many people, and the title of “America’s Dairyland” is even enshrined on the state’s license plates. While Wisconsinites may take the prominence of cows for granted, though, it turns out Wisconsin wasn’t always the Dairy State — at one point in history, it might have even been called the Wheat State.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Wisconsin has long been defined by its agricultural legacy with good reason. The region received an influx of rich soil with the last ice age, which allowed Wisconsin to become a top wheat producer in the early days of statehood. Wheat was a profitable crop in high demand for farmers in the state, and for a brief period in the mid-1800s, Milwaukee was even the busiest shipping port for the grain in the entire world. Fast-forward to the present day, and the Great Plains states are known for their bountiful grains, while Wisconsin is instead renowned for dairy.

During the mid-to-late 1800s, the course of Wisconsin’s agricultural path was forever altered by a number of factors. Fluctuating wheat prices and overworked soil might have been the primary drivers, but dry weather and a tiny insect also pulled on the reins of history.

Just as mosquitoes can thrive after heavy rains, other insects flourish under hot, dry conditions. Droughts of the 1860s, ’70s and ’80s set the stage for biblical outbreaks of some insect species across many parts of the United States. To the west of Wisconsin, fields in the Great Plains fell victim to swarms of Rocky Mountain locusts (Melanoplus spretus), an extinct species once so massive that they darkened the sky for thousands of square miles.

Closer to home, the pest delivering a coup de grâce to Wisconsin’s wheat fields was the humble chinch bug (Blissus leucopterus), which thrived under the dry conditions of the era.

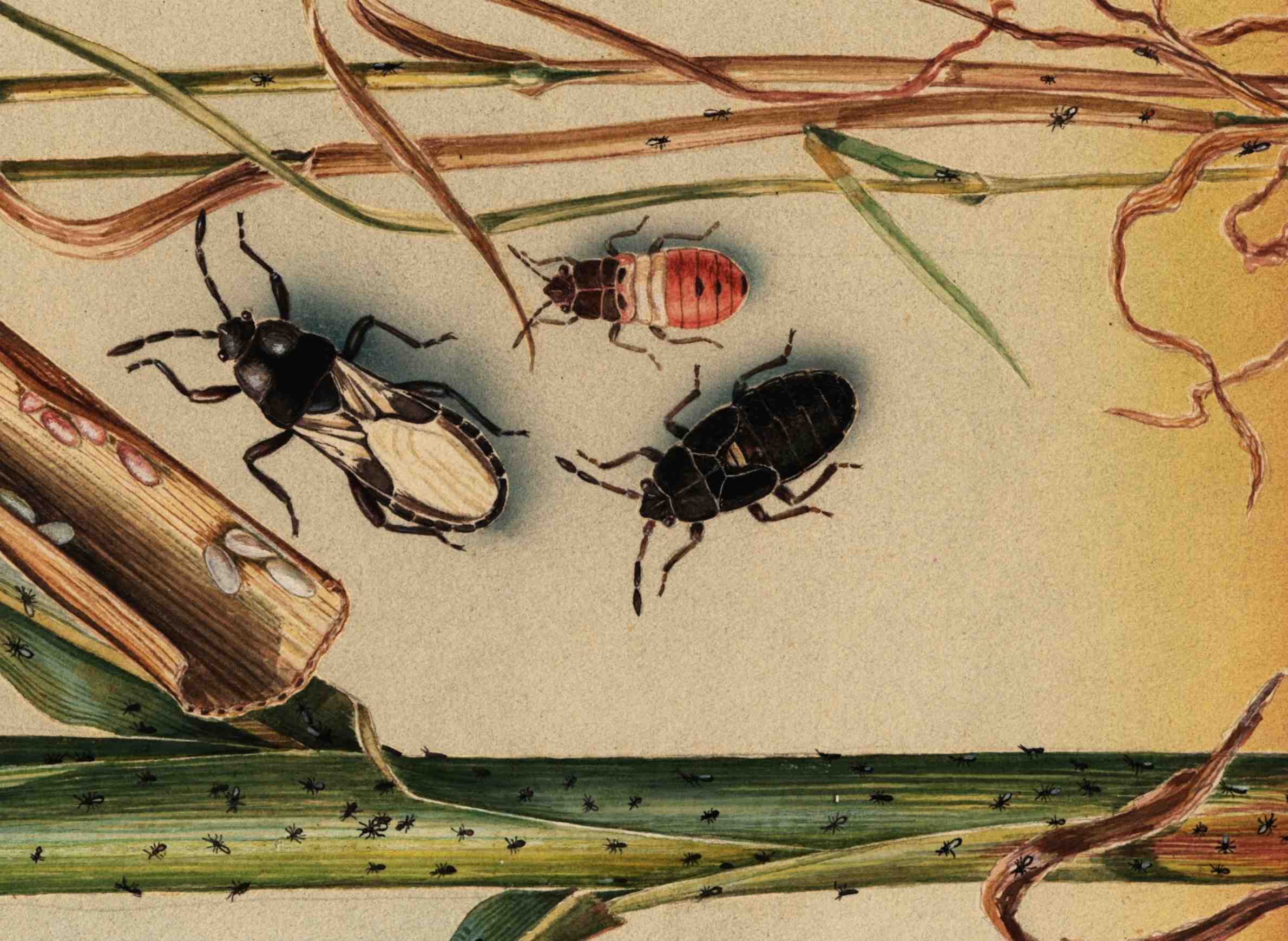

Chinch bugs aren’t much to write home about: with adults measuring roughly an eighth of an inch long, most folks wouldn’t take the time to examine these tiny insects. Even smaller in the juvenile stage when they’re reddish in color, the bugs become black-and-white as they mature. Overwintering adults become active when temperatures rise into the 70s (Fahrenheit).

Two generations of chinch bugs can develop per year in Wisconsin. Adult females can lay several hundred eggs, with it taking nearly a month and a half for the next batch of chinch bugs adults to mature. With their astonishing reproductive capacity, the sheer abundance of these creatures allowed them to devour Wisconsin’s wheat fields in the late 1800s. Using needle-like mouthparts, these insects sucked the life out of wheat plants, leaving behind wilted, yellowed stems.

When a pest outbreak occurs in a given year, a farmer might chalk it up to bad luck, bad weather or other factors, and hope things improve the next season. But with falling prices and the repeated devastation wrought by chinch bugs on fields, Wisconsin’s wheat farmers realized that their efforts yielded little profit. Without an effective way to prevent the ravages of the chinch bugs, attentions shifted to more fruitful possibilities.

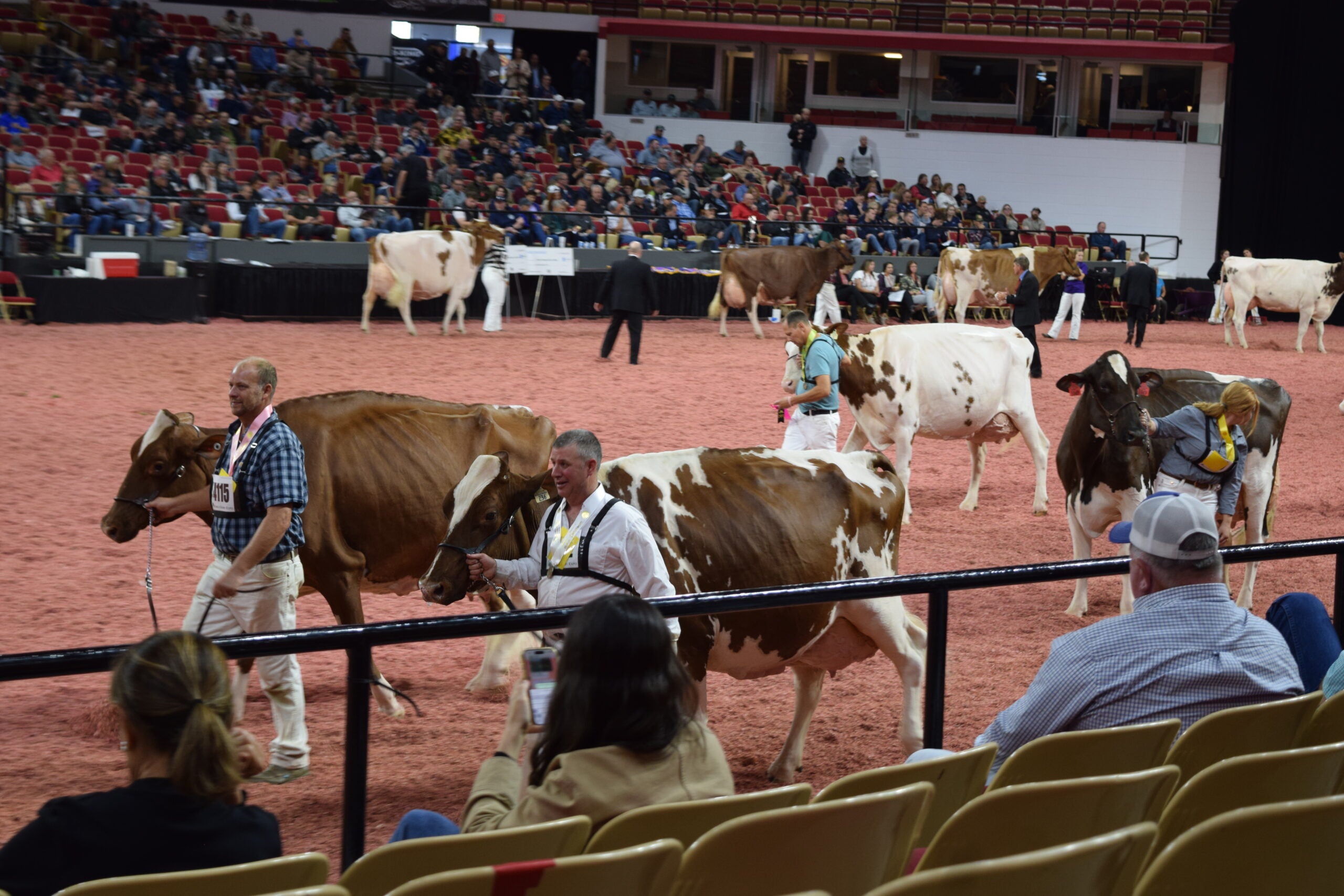

Understanding the biology of the chinch bug was crucial to discovering the limitations of that insect’s destruction. It turns out that chinch bugs are picky eaters with a taste for grasses like wheat and corn. Unrelated plants, including forage crops like alfalfa, weren’t affected by these insects and could be grown to feed livestock. This preference was discovered at the very time that the dairy industry was budding in Wisconsin. Decades later, the state’s dairy prominence is celebrated with festivals, foam hats and other memorabilia.

Most people probably don’t think about insects when enjoying cheese curds, ice cream and other dairy treats — but their outsized role in the state’s identity are a result of the tiny chinch bug.

Editor’s note: University of Wisconsin-Extension entomologist PJ Liesch is director of the University of Wisconsin-Madison Insect Diagnostic Lab. He blogs about Wisconsin insects and can be found @WiBugGuy on Twitter. Wisconsin Public Radio’s “The Larry Meiller Show” interviewed Liesch on June 20, 2018, when he discussed the chinch bug’s effect on Wisconsin’s agricultural landscape.

How A Tiny Insect Set The Stage For Wisconsin Dairy was originally published on WisContext which produced the article in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television and Cooperative Extension.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.