In many ways, the COVID-19 pandemic has been good for the country’s pets. Over the past year and a half, pet adoption rates were up, animal shelters were practically empty, and pet owners were home more.

But for veterinary care providers, it has been a very different experience.

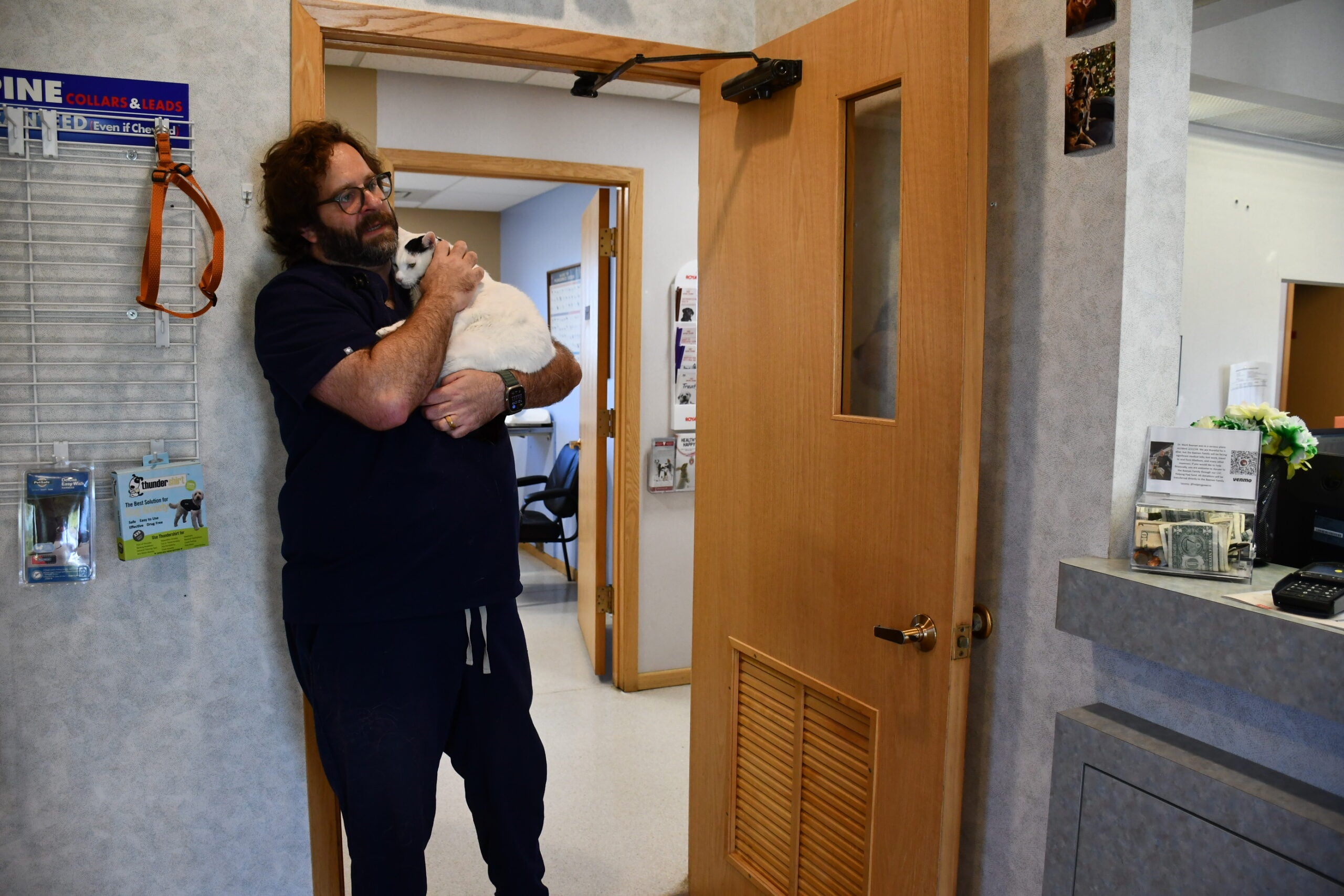

“It was tough,” said Jackie Forcey, a veterinarian at Verona’s True Veterinary Care. “Burnout has been one of the biggest challenges that the vet field faces, and it just has been such a high demand for everybody that it’s still been difficult.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Veterinary staff were declared essential workers early in the pandemic, but only for urgent care. Providers say this forced them to navigate difficult triage situations and created a backlog of nonemergency services that clinics are still wading through today.

“We’re still playing catch-up, and we’re playing catch-up quite a bit,” Wisconsin Veterinary Medical Association Executive Director Jo-ell Carson told WPR’s “Central Time.”

Some are quick to point to an explosion of new pet owners to explain the increased demand on veterinary clinics. But that’s not entirely accurate.

Overall shelter pet adoptions in 2020 were the lowest they’ve been in five years, but intake also dipped substantially during this time. The remaining pets were just getting adopted faster, which explains the empty cages.

Instead, vets say that pet owners — new and existing — were simply paying more attention to their pets, finding lumps, bumps and symptoms they had never noticed before.

“You just had this influx of owners who were now at home and all they were doing was focusing on their pet, because they used to be at work every day,” said Forcey.

She said that sustainable growth for a veterinary practice her size is generally about 20 new pets per month. Since April 2020, her office has seen 1,058 new pets — nearly 60 per month.

Veterinary appointment bookings grew by 4.5 percent in 2020 and are on track to grow by nearly 7 percent in 2021, according to a report from the American Veterinary Medical Association.

But this boom in business is happening while veterinary practices are operating with reduced capacity in order to meet COVID-19 safety protocols.

“What we’ve seen is the pandemic has brought this huge decrease in how efficient we can be in our clinics, which has made the backlog increase,” said Carson.

According to the association report, productivity declined by 25 percent in 2020 because of COVID-19 protocols. At some clinics, owners can no longer accompany their pets inside. This means that a veterinarian has to spend time speaking with the pet owner before and after the exam, which adds time and limits how many patients can be seen in a day.

During the height of the pandemic, clinics were also limiting the amount of nonemergency services they provided — things like annual wellness check-ups, vaccinations, and spaying or neutering. This has led to backlogs and long wait times that may frustrate pet owners but are felt acutely by the state’s animal shelters.

“Our biggest challenge is the fact that the veterinarian clinics around our area, who are amazing, are unfortunately so backed up that it’s causing a delay in our adoption program,” said Amy Quella, executive director of Bob’s House for Dogs near Eau Claire. Her organization focuses on geriatric dogs and dogs who often need substantial medical attention before they are ready to be adopted. While they wait for appointments for one dog, it often means turning away another because they don’t have room.

Many shelters across the state require cats and dogs to be spayed or neutered before they can be adopted. When there are substantial delays in these procedures, shelter staff say it’s much harder to coordinate adoptions. In turn, this can lead to overcrowding, especially in shelters who rely on external providers for veterinary care.

“With their current clients they’re already so behind and then 15 people adopt animals and they go, ‘Oh crud, I have to find a veterinarian,’” said Laura Berchem, executive director of the Humane Society of Sheboygan County. “Anyone they call right now is going to say it’s going to be six to eight weeks before I can see you.”

Berchem said her team is lucky to have in-house vet services, but she knows it’s more challenging for their adoption clients to get care for their pets.

According to veterinary and shelter staff, increased demand is only half of the equation. The industry is also plagued by a familiar ailment: worker shortages.

“Our industry is facing the same staffing shortages, fatigue and burnout from all the emotions that we’re all feeling on a daily basis,” said Amanda Reitz of Happily Ever After Animal Sanctuary near Green Bay.

And like other industries facing labor shortages right now, these issues pre-date the pandemic.

The American Veterinary Medical Association says vets have one of the highest annual turnover rates among medical professions, just behind registered nurses. The highest rate of turnover is actually among vet technicians.

In an ideal staffing model, Forcey said a veterinarian should have four support staff. She has one. And her entire clinic shares one receptionist. They’ve hired two new doctors, but can’t find people to fill their support positions like vet technicians and receptionists.

“A lot of people realize that the vet field is great and there’s a lot you can do, but also there’s probably a lot of other jobs out there that pay you more and aren’t as demanding — physically, mentally and emotionally,” said Forcey.

Carson said that as restrictions are lifted in some areas, veterinary clinics are starting to catch up, but they still have a long way to go. Continued worker shortages could make it difficult to recover fully, which is not great news for animal shelters.

“It is something that has the ability to really significantly impact this work,” said Alison Kleibor, executive director of the Wisconsin Humane Society. “It’s not easy to become a veterinarian and so when there’s a shortage of them it’s not easy to backfill and to find a replacement. So it’s somewhat of a crisis in the industry.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.