For walleye spearfishers and anglers, knowing how many fish are in a given lake is a big deal.

Population estimates are what set bag counts for fishers. For a popular sport and eating fish that has experienced decades of decline in many lakes around the state, the stakes are high against the risk of overfishing.

But getting an accurate count isn’t an easy feat — it’s time and resource intensive and only occurs on roughly 5 percent of Wisconsin’s more than 900 walleye lakes, said Mike Spear, a Ph.D student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Limnology.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“Trying to manage 900 systems based on, you know, roughly only 5 percent of those lakes is a tall task,” he said.

Traditionally, researchers gather the data using a “mark and recapture” method, where a crew of biologists and technicians set nets in the lakes, capture as many fish as they can and mark them.

A few days later, they return to the lake and electrify the water, capturing as many fish as possible — they then estimate the total population based on the number of fish they catch the second time that are both marked and unmarked, Spear said.

Yet in a recently published study looking at walleye populations, Spear and his colleagues say there may be a faster, easier and cheaper way to do it: environmental DNA. Spear likens it to gathering DNA at the scene of a crime to see who was present.

“Similarly, we can go out into the environment and take a sample from the water or the dirt in that environment, and it contains traces of plants and animals that are there or have been there,” he said.

Researchers can gather samples of water in something as simple as a few water bottles and take them back to the lab for testing. The time in the field can be as quick as 20 minutes, he said.

“It’s pretty low tech and really not personnel or time intensive at all,” Spear said. “Whereas the traditional technique, you’d need many technicians and big electro-shocking boats and fishing nets.”

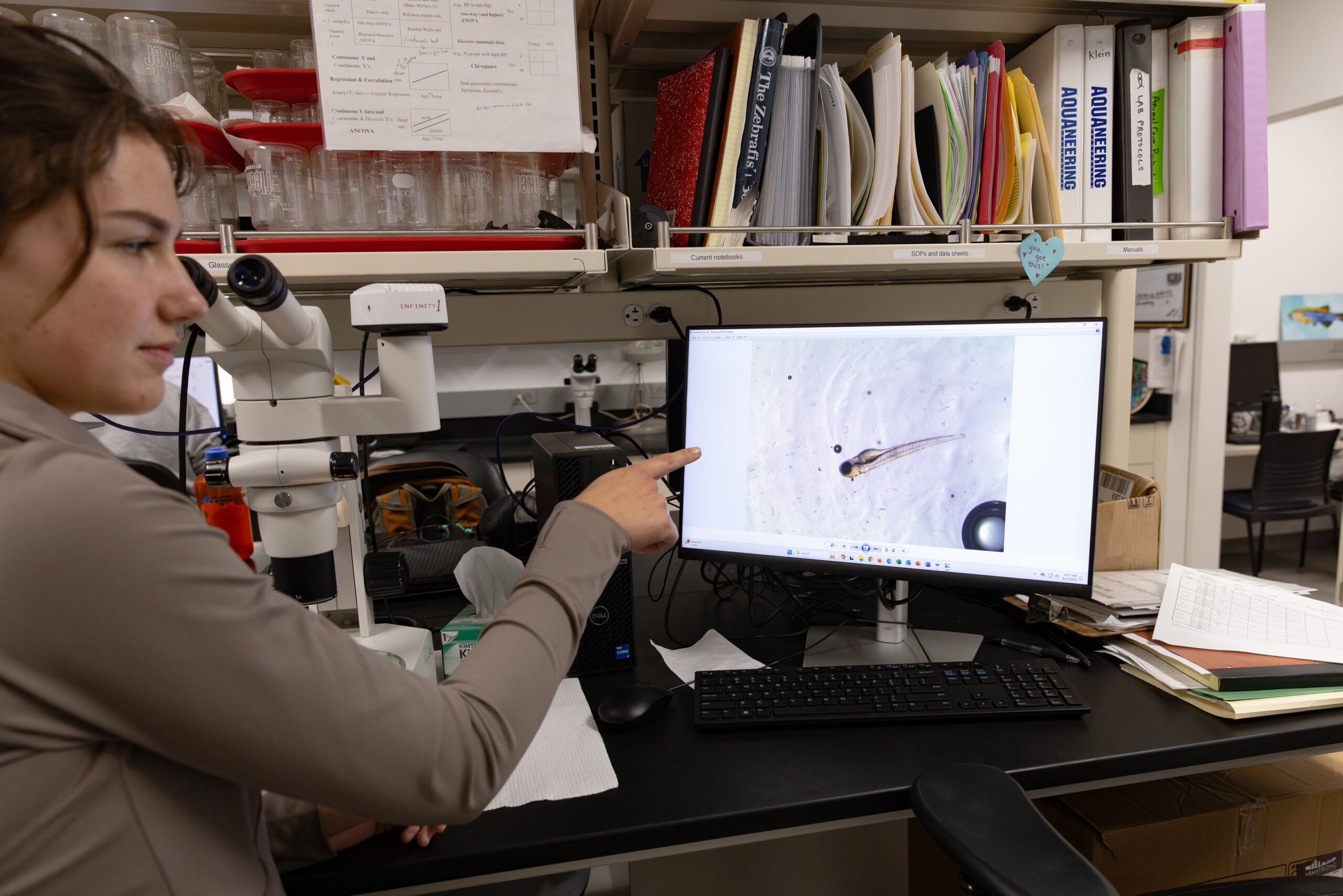

While it simplifies things on the front end, it’s a little more complicated on the back end, Spear said, when researchers bring the water samples back to the lab, filter and extract the DNA from those samples and match it to the walleye DNA.

Researchers have collected data from 24 lakes in the past couple of years, Spear said. The data collected shows a strong correlation between the traditional mark and recapture method and the environmental DNA method.

“We’re able to predict with pretty good confidence how many fish might be in a lake, to the effect that we would know when to close the lake down to fishing, limit the bag size on a particular lake or know when we can go with a business as usual approach,” he said.

The environmental DNA method isn’t meant to entirely replace the traditional sampling method, Spear said, but rather be a complementary method that could help scientists expand beyond testing populations of just 5 percent of the state’s lakes.

“From a biologist’s perspective, there’s no better thing than to have a fish in hand,” he said. “There’s a lot of uncertainty when you’re obliquely sampling a population with sort of secondary evidence, this DNA that’s left behind. You’ll never know necessarily the size of any individual fish, or the ratio of the sexes or other important demographic information.”

Currently, researchers from the UW Center for Limnology are working with the United States Geological Survey to expand DNA sampling beyond walleye to get a full picture of the fish present in a given lake.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.