Wisconsin native Nathaniel Frank grew up following turtles and flipping over rocks to look for salamanders. He’s been keeping reptiles and amphibians since he was 6.

“As a little kid I wanted to keep venomous snakes, and as I got older, I decided to start keeping some snakes that no one else was keeping in the United States,” he said.

Over the last decade, his passion has led to a unique business. It started when the University of Queensland in Australia reached out to see if Frank could provide venom for research from one of his rare species. His company grew from there.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Now Mtoxins is one of fewer than a dozen labs across the globe producing the venom that goes into antidotes for snake bites and scorpion stings, Frank said. He can’t share all his lab’s clients —some have NDAs — but its venom is used for both therapeutics and research. The lab, which has four employees and a steady stream of interns, has contributed to about 25 published studies.

Mtoxins even helped researchers reclassify the world’s most venomous snake from the inland taipan — which Frank keeps in Oshkosh — to the Malaysian blue coral snake. (Frank has a particular interest in coral snakes. His company was originally called Micrurus Toxins, after their genus, but he shortened it to Mtoxins after people struggled with the pronunciation.)

Recently, a new client has led MToxins to scale up. With extra space at a new location, Frank decided to open a portion of the lab to the public. Now visitors can watch live venom extractions and learn about the important role venomous animals have played in our own understanding of human evolution.

Seeing Extractions In Action

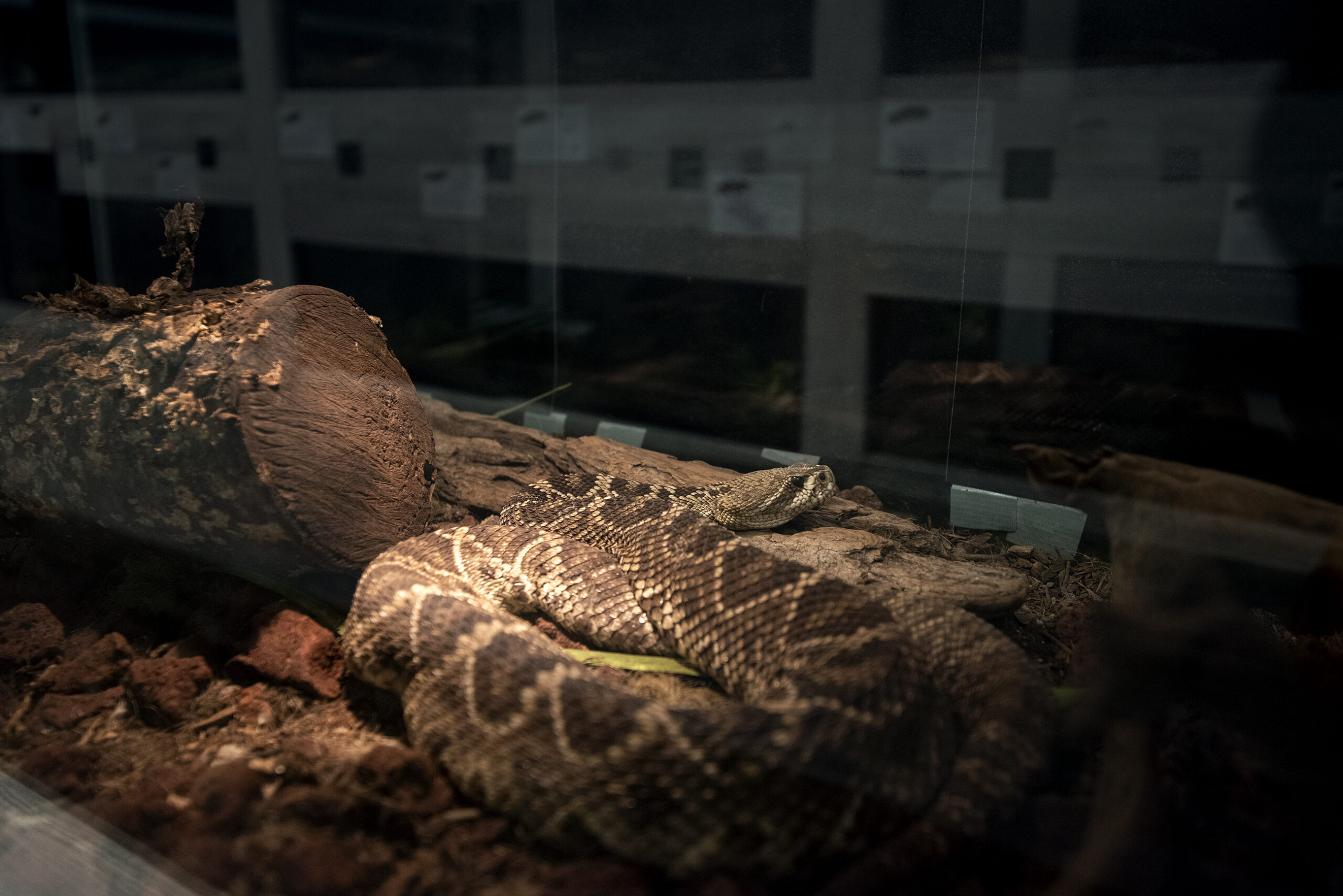

At MToxins, there are more than 1,000 animals, including some of the world’s most venomous creatures. The lab is open with special safety precautions in place during the coronavirus pandemic. Visitors can see eastern diamondbacks, green mambas and other species on display.

In December the menagerie included a pair of porcupines and a parrot, which allow staff members to expand their discussions with visitors on evolutionary research and conservation, Frank said. Many of the animals come from partnerships with zoos, and a breeder in Florida provides most of the venomous snakes, Frank said.

Some of the animals on display at Mtoxins can’t be found at any zoos in Wisconsin or in the surrounding states, he said. But the real draw takes place behind a plate glass window.

Before entering the extraction area, Frank goes through the same “IMSAFE” checklist used by pilots — illness, certain medications, stress, alcohol, fatigue or emotion could put him at risk while handling potentially deadly animals, he explained.

Inside Frank uses a hook to wrangle each snake from its crate, ultimately gripping near its head. He doesn’t wear any armor to protect against bites, which are exceedingly rare. The snakes can vary dramatically in size but handling each one requires the same level of vigilance, Frank said.

Next, he brings the snake toward the glass, to a table in front of the window. Visitors might get a chance to lock eyes with a king cobra before Frank presses its head toward a sterilized chalice until its fangs pierce a clear covering and its venom collects inside.

While it’s a spectacle that visitors seem to real get a kick out of, Frank said, he’s just keeping up with production demand.

Each snake can give venom about every two weeks. If a snake is acting lethargic, it gets the day off, Frank said. Mtoxins also offers venom from centipedes, spiders and scorpions.

“We try to be as ethical as is humanly possible, and that’s why we have so many (animals), because if an animal is having a bad day, I don’t want to risk being bitten, and I don’t want to put the animal through that,” he said

The venom is purified and dehydrated, so it can be sent to antivenom manufacturers and research labs as a fine powder, typically going for $1 to $5 per gram, Frank said.

Lifesaving antivenom is made by injecting small doses of the venom into host animals — often horses — until they’ve built up immunity … then extracting their plasma to create a treatment akin to a vaccine.

A Dose Of His Own Antivenom

The powerful neurotoxins in the venom of a black mamba can start working in minutes. It’s one of the reasons the snakes — which can reach 14 feet long — are among the most feared animals in Africa.

The black mamba is the first species of venomous snake Frank ever touched. After thousands of extractions over the course of his career, it’s also the only one that’s left him in need of antivenom himself.

Frank was bitten by a black mamba in September. The snake itself is relatively small and now permanently on display at MToxins, where it’s been retired from the venom line.

“I had a stern talking-to with the snake,” Frank said. “They don’t have ears, but I know he felt the vibrations.”

After the bite, Frank brought his antivenom to the hospital. He was treated and released hours later. But it was a painful and frightening experience, he said.

“Every person’s body reacts to venom differently,” he said. “You and I could be bitten by the same snake, the same amount of venom. … You may have underlying kidney issues that you never knew about, and that venom attacks your kidneys. I may be able to have pain meds only and go home the next day.”

Preparedness is key — the nearby hospital, local fire department and Wisconsin Poison Control Center are all aware of the work taking place at Mtoxins, he said.

Frank’s friend Dr. Leslie Boyer, a toxinologist at the University of Arizona College of Medicine in Tucson, says every bite is a living science experiment. And after a bite, time is tissue, Boyer said. It’s important to get treatment as soon as possible.

“I see quite a few people who have been stung by scorpions or bitten by snakes and need emergency care,” Boyer said. “It still is possible to die from snakebite. Fortunately, good medical care prevents that.”

Snakebites Are Still A Big Problem

Unsurprisingly black mamba bites in Oshkosh are rare. In fact, Wisconsin has recorded just one confirmed fatal snakebite since 1900, according to the state Department of Natural Resources. The endangered eastern massasauga and the timber rattlesnake are the only venomous species native to Wisconsin.

But around the world, it’s believed more than 100,000 people die from snakebites each year, and many more lose limbs or suffer other disabilities. In fact, the World Health Organization labeled snakebite a neglected tropical disease in 2017. A recent study estimates more than 1 million people in India died from snakebites over the last 20 years.

“It’s a pretty multifaceted problem, so we try to hit it from as many angles as we can,” said Jordan Benjamin, a wilderness paramedic and founder of the Asclepius Snakebite Foundation, which runs a clinic in Guinea that offers public health education, training for health care workers and free treatment.

MToxins venom is used to make the antivenom the clinic administers, Benjamin said.

In Africa, about 95 percent of venomous snakebites occur in rural areas and less than 5 percent of victims receive antivenom, he said. A variety of factors drive people away from hospitals, including distance and price.

Instead, most people see traditional healers, Benjamin said. And because many African snakes aren’t venomous (and even venomous snakes fail to inject their toxins about a quarter of the time), the experience can leave many snakebite victims thinking they were cured when they were never actually ill, he said. The positive outcome makes people more likely to see a traditional healer again if they receive another bite, Benjamin explained.

For these reasons, it’s not profitable for hospitals to stock antivenom or for manufacturers to make it. In fact, there’s a global shortage.

Venom Can Unlock The Secrets To Future Treatments

Antivenom is still critical for treating bites, but it’s old medicine, Boyer said. At the same time, venom is also being used to make cutting-edge medical discoveries.

Over the course of human history, we’ve evolved defenses to protect us from predators. But venomous predators, including snakes, have found ways to circumvent those defenses. It’s no coincidence snakes know something humans can learn from, she said.

“They have little molecules that fit perfectly in our hearts and in our blood vessels and in our tissues and in the materials that clot our blood,” Boyer explained. “And it turns out that the very same substances that make my patients so sick that they could die or lose a limb, if you tease them out and study them one at a time, could be the next miracle drug.”

Snake venom that stops blood from clotting is used in heart medications. And there are other examples too. Venomous Gila monsters, which live in the southwest U.S., must quickly produce insulin when they come out of hibernation. Saliva from the animals is used in diabetes medication, Boyer said.

Those possibilities are what Frank hopes visitors will take away from a trip to MToxins, he said. The venom he’s extracting can do a lot of damage, but it can do even more good.

“These animals serve a purpose, and they don’t chase you,” he said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.