Wisconsinites generally expect mosquitoes to be “bad” from late spring through the summer months, but for the pesky sanguivores to typically fade away as autumn approaches.

However, September 2018 definitely bucked the trend, and as a result, mosquito pressure was very high in many parts of the state and around the Midwest.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

As with other mosquito matters, the common denominator was water — in this case, the unprecedented rainfall events over one week and the next in late August, and again in early September. During this time, a series of storms dropped heavy rains across large swaths of Wisconsin and surrounding states. Much of southern and central Wisconsin received several inches of rain, and some counties were inundated with 10-plus inches of rain in short periods of time. Devastating flooding ensued, and it was only a matter of time before the mosquitoes responded as well.

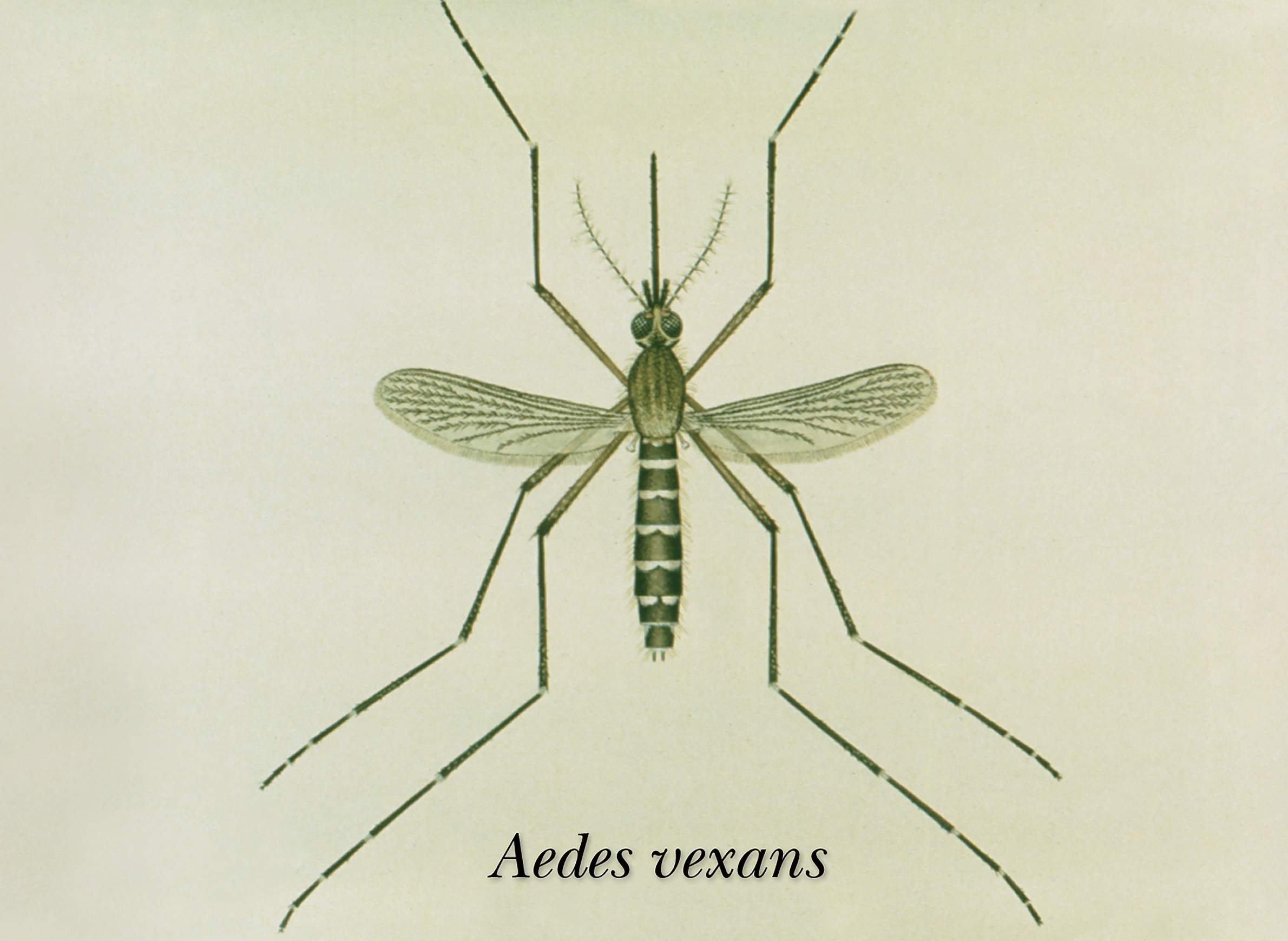

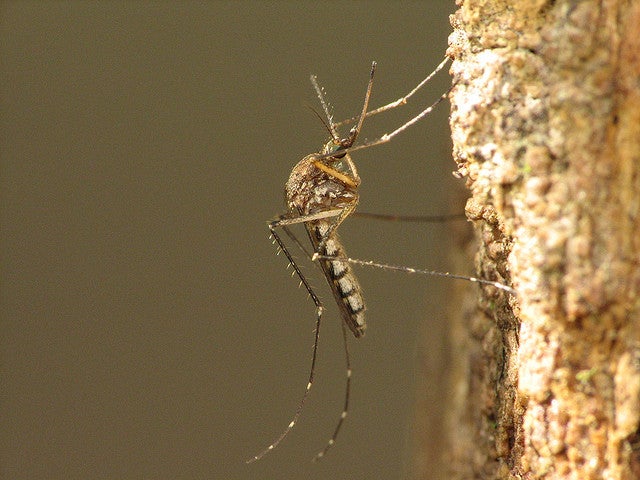

Surprisingly, not all mosquitoes can take advantage of floodwaters, and some species have a strong preference for more permanent bodies of water, such as tree-holes, man-made objects, marshes and other areas that see standing water for weeks or months on end. Out of the more than 60 mosquito species in the Midwest, it was much smaller subset that flourished following the deluge — a group appropriately called the “floodwater mosquitoes” for their ability to use temporary water sources to their advantage. Members of this group, including the abundant inland floodwater mosquito (Aedes vexans), tend to lay eggs in low-lying areas without water. Laying eggs away from water might seem like a counterintuitive strategy, but these hardy eggs simply bide their time until heavy rains arrive — in some cases, years later.

Relying upon temporary resources can be a risky strategy; if the waters dissipate too quickly, stranded larvae or pupae can be doomed. As a result, floodwater mosquitoes have evolved to race against the clock, with eggs that hatch shortly after exposure to water, followed by hasty growth and development. Under the right conditions, it can take less than a week for these mosquitoes to make it to the adult stage. This scenario is exactly what played out in parts of Wisconsin — the rains came, followed shortly thereafter by hordes of hungry adult mosquitoes.

When unseasonably high mosquito pressure occurs, one of the questions asked most often is, “When will it stop?!”

Mosquitoes and other insects are cold-blooded creatures, so there’s a general relationship between warmer temperatures and insect activity. Most insects in the Midwest become lethargic when temperatures dip into the 50s; below 50 degrees Farenheit, mosquitoes are often too lethargic to fly, let alone pursue a blood meal.

While mosquitoes were particularly plentiful throughout the warm months of 2018, the unusually high mosquito activity around parts of Wisconsin in early and mid-September occurred when temperatures remained in the 70s and 80s most days. A return to more seasonal weather in many parts of the state provided relief, as plunging evening temperatures proved too chilly for mosquitoes to go about their business and early frosts provided the final nail in the coffin for the floodwater mosquitoes.

When troublesome mosquito populations persist into the fall, the best way to deal with them may be to embrace “flannel season” and wear long-sleeved layers as a physical barrier to bites, and use U.S. Environmental Protectionn Agency-approved repellents as needed (such as on warm days). Avoiding prime mosquito feeding times around dawn and dusk and steering clear of mosquito-friendly habitats can help avoid bites as well.

It may be sad to see summer gone, but the falling leaves and cooler temperatures also signal the seasonal winding down of mosquito activity around the Upper Midwest.

Editor’s Note: University of Wisconsin-Extension entomologist PJ Liesch is director of the University of Wisconsin-Madison Insect Diagnostic Lab. He blogs about Wisconsin insects and can be found @WiBugGuy on Twitter.

Why Wisconsin Saw A Surge In Mosquitoes As Summer 2018 Ended was originally published on WisContext which produced the article in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television and Cooperative Extension.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.