In the system of checks and balances, the third branch is key. Made up of the supreme, appellate, circuit and municipal courts — the judicial branch — interprets the laws. But how are those interpreters, or justices, put on the bench?

Wisconsin resident Helen Leong wanted to know, so she wrote into WPR’s WHYsconsin to ask: “Why are Supreme Court justices elected in a popular vote?”

When we asked what prompted her question, she said she had lived in several states, and had never elected a justice through a popular election.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“After the most recent election, I couldn’t help wondering, why does Wisconsin have this system? Did something in the history of the state trigger this process?” she wondered.

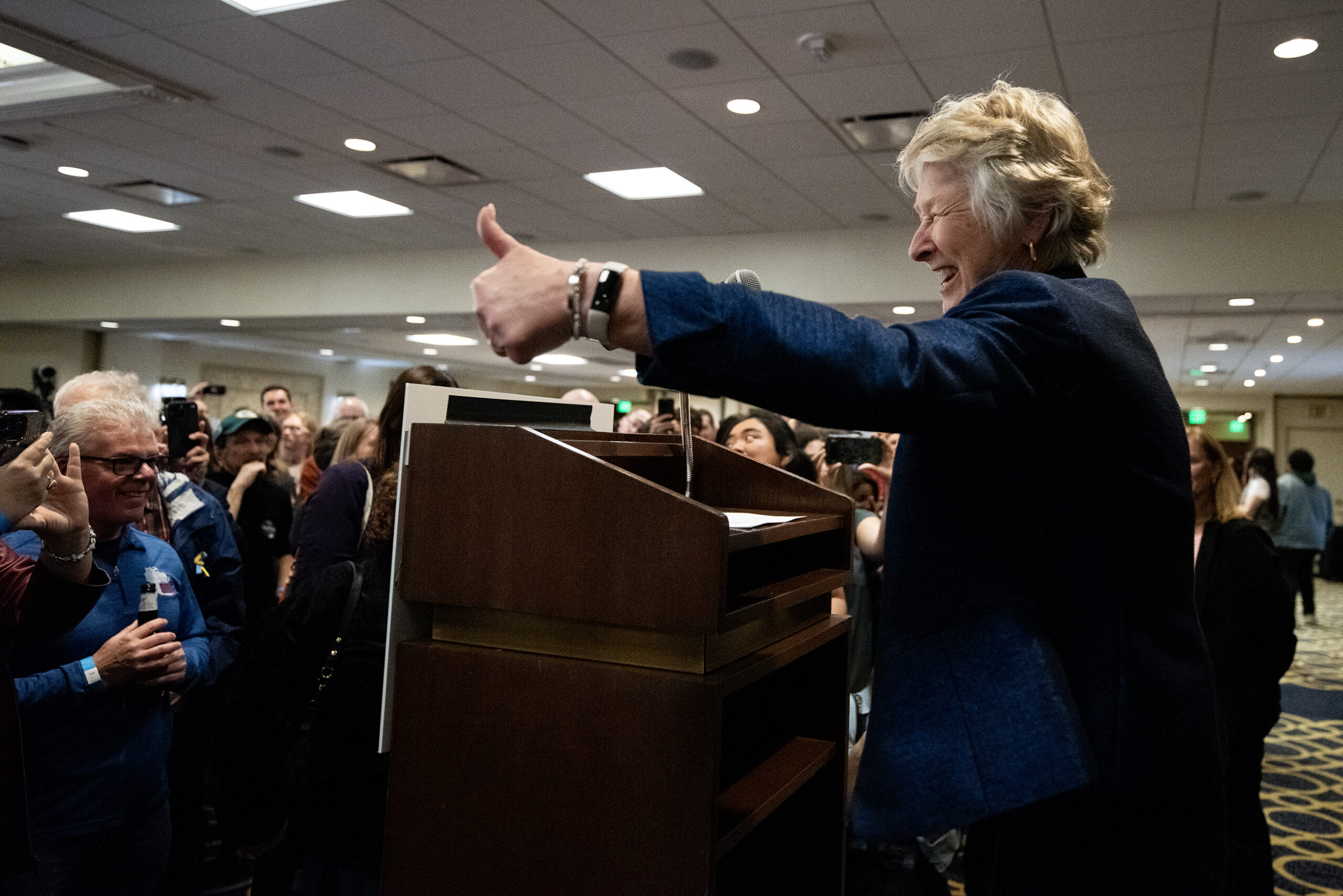

So we turned to an expert to learn more. Janine Geske is a former Wisconsin Supreme Court justice, serving from 1993 to 1998. She’s also a retired Marquette University law professor.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Jenny Peek: For starters, can you explain how Wisconsin’s Supreme Court justices are put on the bench?

Former Supreme Court Justice Janine Geske. Photo courtesy of Marquette University

Janine Geske: Supreme Court justices, as all our judges in Wisconsin, run for election. In particular, our Supreme Court justices have to have been lawyers in Wisconsin for at least five years and they are then eligible to run for the court. The constitution was set up in a way that only one justice is up at a time. So, you will never have two justices running for their seats. Part of the reason for that is to build stability into the court.

The justices’ terms are 10 years … however if a justice either dies or retires or gets appointed to another court and leaves a vacancy, then the governor has an opportunity to make an appointment for that position. That new justice will stay in that position until a year in which there is no election for another justice because two cannot run at one.

JP: How long has the state done it this way?

JG: Actually, there was a debate at our constitutional convention in 1846 and then in 1848 about whether we should have an elected judiciary or an appointed judiciary. As your listener pointed out, different states do it differently. Wisconsin was very much a progressive state. It was deeply debated and it was a divided issue at the time of the constitution, but ultimately the founders decided that we should allow the people to elect the judges.

The debate at that time was between fearing that if people were elected they would only decide whatever was popular as opposed to what maybe be legal versus the fear that if you let people be appointed it was going to be the politically elite who got appointed.

JP: Wisconsin elects its judges in a nonpartisan election. What do we mean by nonpartisan?

JG: Well it is not so obvious what is a nonpartisan election and actually when we started having elections in the 1800s they were partisan. For a while political parties would nominate somebody as the party candidate and judges and justices would run actually on a party. That happens in other states; for example, Texas.

I think it was around the 1900s — there was a concern that you were getting candidates that were standing for principals of a particular party versus an independent judiciary who would look at the issue and decide it regardless of what the partisans believed about it but solely on the law. And so what ultimately became a very strong tradition in our judiciary races was that judges were nonpartisan. They were not allowed to belong to a political party or contribute to a political party, they were not to stand as a partisan judge.

JP: How do other states choose their state Supreme Court justices?

JG: Many states do it in lots of different ways.

Most of the original colonies actually have an appointed judiciary. A lot of them will have a commission — sometimes appointed by the governor and the Legislature and the State Bar — of experts who will go through the names of applicants and look for people who are interested in a judgeship. Then they will give some names to the governor, the governor will select somebody, and in some states you have to have a confirmation like at the U.S. Supreme Court by the Legislature.

Then a number of states have what is called the Missouri Plan. The Missouri Plan was established after Missouri was a state and they decided rather than having standard elections for judges, judges would run on their own records. What I mean by that is that, for example, if I had my 10-year term and it was time for me to stand re-election, only my name would be on the ballot. Depending on the state, I would have to get a certain percentage of approval rating … and if I did, then I was elected for another 10 years. If I did not get that (approval rating), I would be off and the governor would go through a process of appointing somebody else. It’s a mixture of appointment handled just by the Legislature and the governor and electing by the public. A lot of people through the years have seen that as sort of a compromise of the two kinds.

JP: Is there anything else you think people should know about this process?

JG: I think the thing that we should always be looking at is whether or not people are having confidence in the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

People will say they want a justice that thinks like them and acts like them, but when it comes down to a particular case or an interest they may have, the best judges and the whole way our Democracy was set up with this third branch of government was an oversight branch that would be neutral, fair and independent. And independent in a way that those judges were not swayed by political whims but in fact by analysis of the law.

Ultimately, we are best served in our three branches of government if the court is independent and we elect people who believe that most important is the independence of that third branch.

This story came from an audience question as part of the WHYsconsin project. Submit your question at wpr.org/WHYsconsin and we might answer it in a future Wisconsin Life segment.