While the rate of tobacco use among Americans has declined overall, the habit which used to be one of the rich has made the slow slide to becoming a burden on the poor. We talk to a behavioral scientist for more. We also talk about those extra questions that make it on the ballot from time-to-time, from gauging Wisconsinites’ attitudes toward marijuana legalization to asking Floridians about the rights of some convicted felons.

Featured in this Show

-

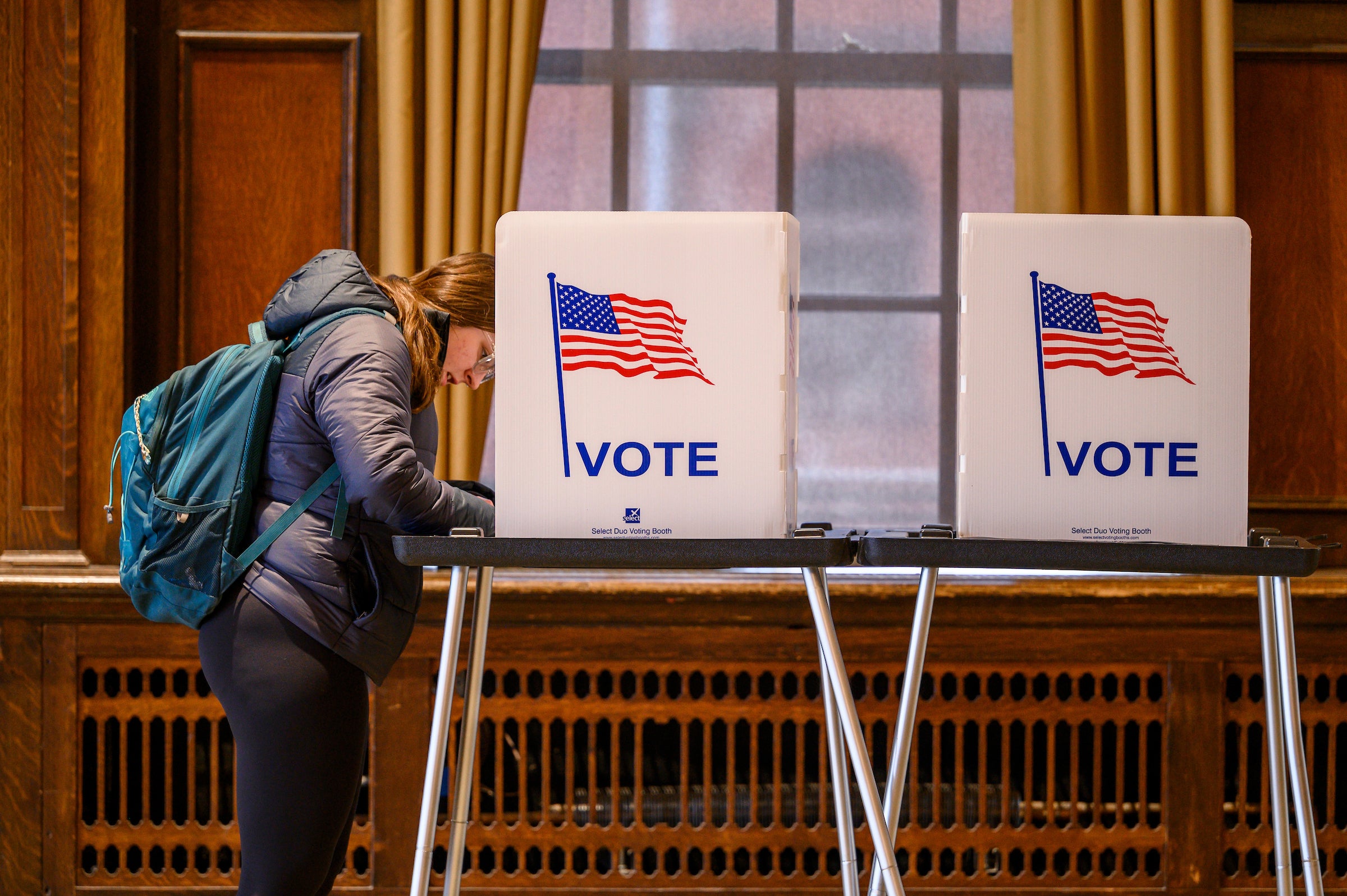

What You Should Know About Wisconsin Referendums

Some Wisconsin voters saw referendum questions on their ballots during the election last week, asking whether they would support a dark store loophole or OK medical marijuana use.

But what do these referendum questions mean, and what’s their purpose?

While some election questions have constitutional changing power or the ability to boot out an elected official, not all referendums are equal.

There are three different types of referendums in Wisconsin, said Staci Duros, a legislative analyst with the Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau.

Advisory referendums, such as the ones seen on the Nov. 6 ballots, have a purpose of informing legislators about public opinion, said David Canon, chair of the political science department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. But that’s the only purpose they serve. Whether a majority of voters support an advisory referendum has no direct impact on legislation.

“These are usually put on the ballot by groups that want to influence policy in the direction that they favor,” Canon said.

While any individual or group can petition that a measure be put on a ballot, governing bodies still have to authorize those items to be on the ballot, Duros said.

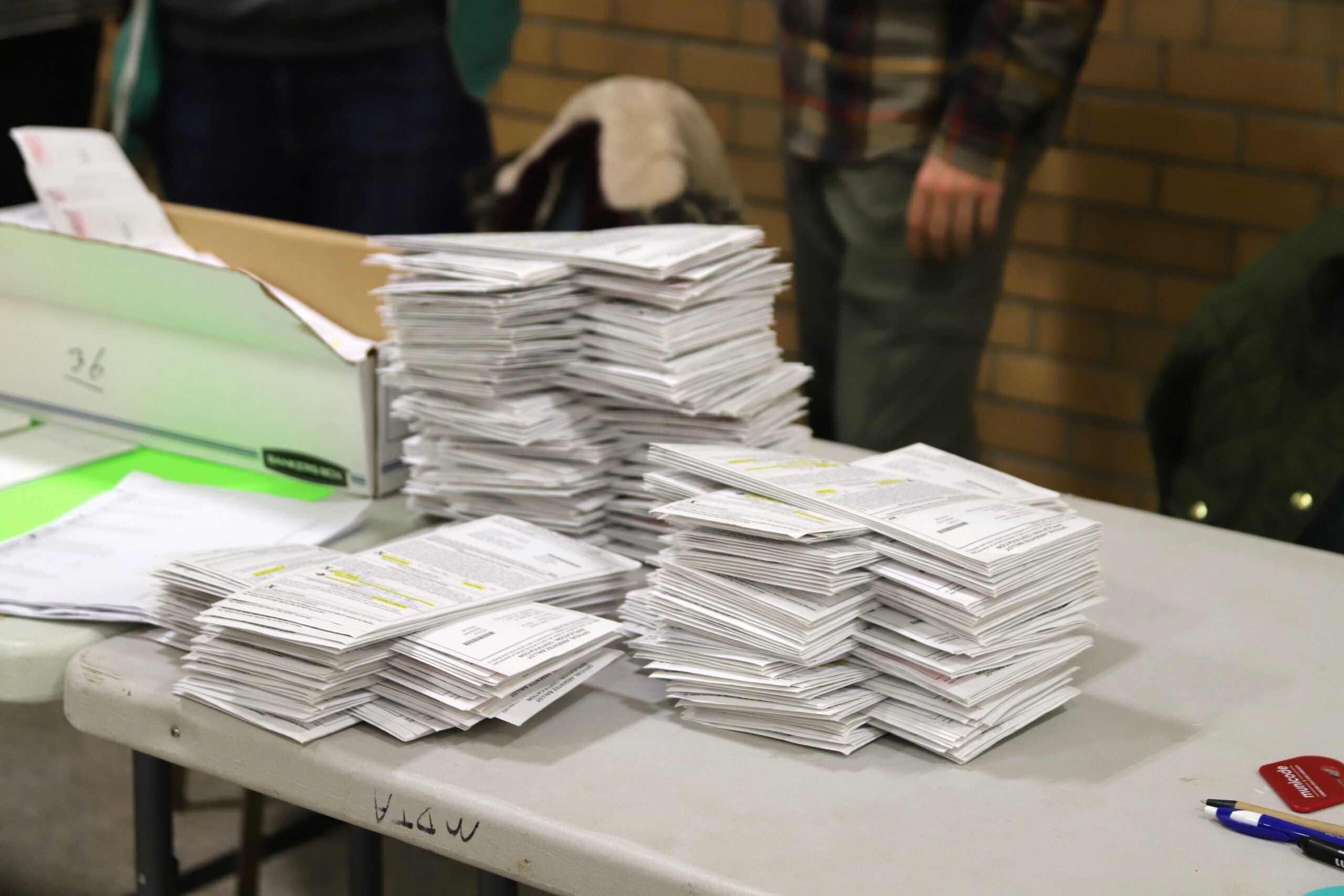

On Nov. 6, voters in 16 counties and two cities across the state voted on referendums asking if marijuana should be legalized. But the difficulty with advisory referendums such as this is that no official criteria for writing them exists, meaning wording between districts is different and often not neutral, Canon said.

In the case of marijuana, some counties asked whether voters would support medical marijuana, while others asked specifically whether all marijuana uses should be legalized.

“It is harder for state legislators who are trying to use this information to be able to say, ‘Yeah, we really know exactly what voters think,’” Canon said.

Petition referendums allow electors to challenge laws that are already enacted, Duros said. Members of the electorate can force a vote on recently enacted legislation, which gives them similar authority to veto power, Duros said. But this power, according to state law, is available only to those in cities and villages.

Petition referendums allow electors to abolish offices for elected county executives, change county seats, incorporate new cities or villages and annex adjacent land, again only to cities or villages.

Direct and indirect initiatives are similar to petitions, but they’re not referendums. These measures allow electors to propose new laws — instead of amending an existing law — without the support of the government or state Legislature at the city and village levels. It does require a certain number of signatures to be validated.

If a village board or city council doesn’t take action on the measure within 30 days, the question is asked of voters on a referendum ballot.

“City legislation adopted via initiative cannot be vetoed by the mayor, and the city council or village board may not repeal or amend the law within two years of its adoption,” according to the state Legislative Reference Bureau.

Finally, the third type of referendums are referred to as binding, which are measures brought before the electors for approval or rejection.

One example of binding referendums are school referendums, which can be used to exceed revenue limits — the maximum amount that districts can raise for spending — or for borrowing for capital improvement projects.

Last week’s midterm elections saw 77 school referendums approved statewide, with voters supporting an additional $1.3 billion in spending for local schools. These referendum questions are written and placed on the ballot by local school boards.

Binding referendums are also required to make constitutional amendments. State law says proposals to amend the constitution have to first be passed by two consecutive sessions of the Legislature. Then, the amendment has to be approved by a majority of voters on a statewide ballot.

Binding referendums can also include those issued by the state Legislature. The transportation fund that was approved in 2014 and passed by a margin of 80 to 20 percent statewide is an example. Canon said 41 of these types of referendums have been passed throughout the state’s history.

“It doesn’t happen very often,” he said.

-

Are Referenda Actually Good For Democracy?

Referenda can be a way for voters to directly affect policy, like Floridians’ decision to restore voting rights to citizens convicted of some felonies, or Nebraskans’ vote to expand Medicaid coverage in their state. But much of the time, referenda aren’t actionable. Advisory referenda, like Wisconsin’s marijuana ballot initiatives, can serve as a way for politicians to claim that public opinion is on their side. That’s in spite of the fact that there are no official criteria for writing these questions in Wisconsin, and as such, the wording often differs from district to district and isn’t neutral.

-

Why The Poor Are More Likely To Smoke

While the rate of tobacco use among Americans has declined overall, the habit still disproportionately affects the poor. A behavioral science professor explains how smoking shifted from a habit of the rich to a burden on the poor. We also explore the consequences of this shift and potential solutions to the problem.

Episode Credits

- John Munson Host

- Colleen Leahy Producer

- Laura Pavin Producer

- David Canon Guest

- Keith Humphreys Guest

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.