In a new comic book series, the main character returns to his small Wisconsin hometown as a failure, mirroring the actual nightmare of co-author and Wisconsin native Tim Seeley.

Seeley lives in Chicago and teaches illustration at Columbia College. He grew up in Ringle, about 15 miles southeast of Wausau, with a population of about 1,700.

During a recent appearance on Wisconsin Public Radio’s “The Morning Show,” Seeley reflected on experiencing a “nagging fear” as a comic artist that he would crawl back to his hometown after falling short on his dreams.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

But success in comics is easier now than when he was a kid, Seeley said. The internet offers more paths for exposure than when he used to leave comics at conventions or in bathrooms hoping to gain more attention.

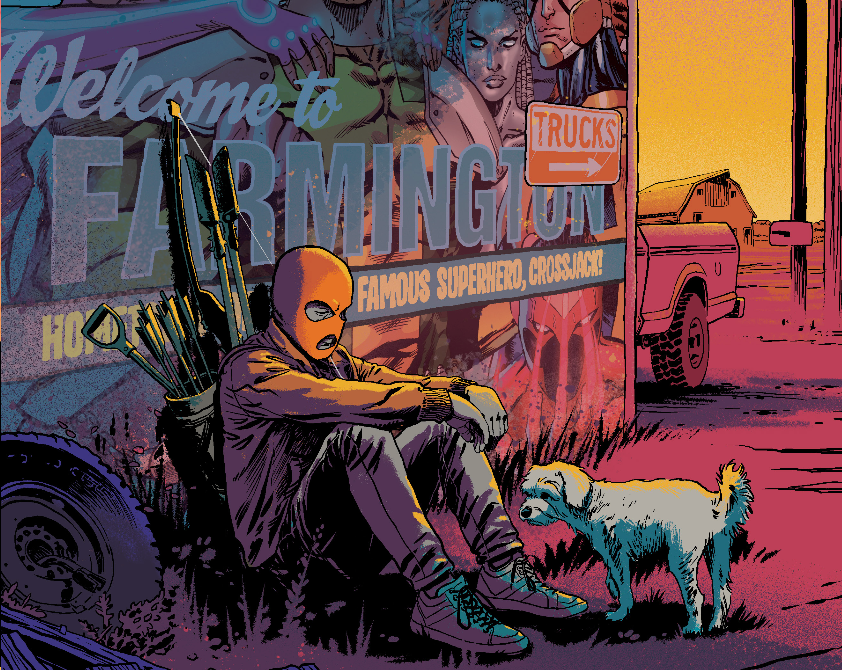

On “The Morning Show,” Seeley discussed setting his latest story in Wisconsin, the genre of rural crime noir and 1990s superheroes. The new comic series, “Local Man,” involves a disgraced former superhero returning home and investigating a murder.

The following was edited for clarity and brevity.

Kate Archer Kent: Why did you make the story in a fictional town but include so many references to real parts of Wisconsin?

Tim Seeley: I felt like I had not seen a superhero story set in rural Wisconsin before. It’s obviously something I have a lot of experience with. I’ve always noticed that we put in details that relate to people. They just sound more honest. The characters inhabit a world that seems more real.

But we made it fictional because the town is kind of terrible in a lot of ways. It’s a town in which all the major industry (has) fled. It’s just holding on by a string. It’s somewhat corrupt, as well. We didn’t want to call out a real place, so we made up a fake place that is a combination of a bunch of different ideas that feels like a town, but it’s also worse than any real town.

KAK: How does this story fit the genre of rural crime noir?

TS: I love those kinds of stories to show these things that people associate with cities — the noir genre almost always takes place in Los Angeles, New York or Chicago — and a lot of those elements play really interestingly in a small town. It’s more intimate. Everybody knows what you’re doing. There’s nowhere to escape.

I did a previous series called “Revival,” which was also set in Wisconsin but in my hometown. This one, I wanted to try a different genre that was more of a supernatural horror story. I dug back into my childhood and pulled out lots of these 1990s superhero ideas and set them in a town that felt very much like some place I grew up.

KAK: What is a day in the life like for these superheroes in “Local Man”?

TS: In the early 1990s, they started making superhero comics pretty much exclusively for 13-year-old boys. Those comics tend to have this very distinct aesthetic in which they’re really aggressive, they’re really brightly colored and they’re often like sexy — but only for 13-year-old boys and for no one else. But they were full of creative energy, and they were full of life. I like them, but I also hate them.

I wanted to tell the story with these kinds of characters. One of my things that we observe in the book is that 1990s superheroes were not that concerned with saving the day. They were more concerned with beating stuff up or looking cool. That was the main motivation for that era of superhero comics. So, we make fun of it. Our character comes from a team of which most of the time he had no idea what it was they were doing. He was just running around beating up bad guys and not really understanding how this helped anyone. But all of them just went through it because it was a way to be powerful, cool and famous.

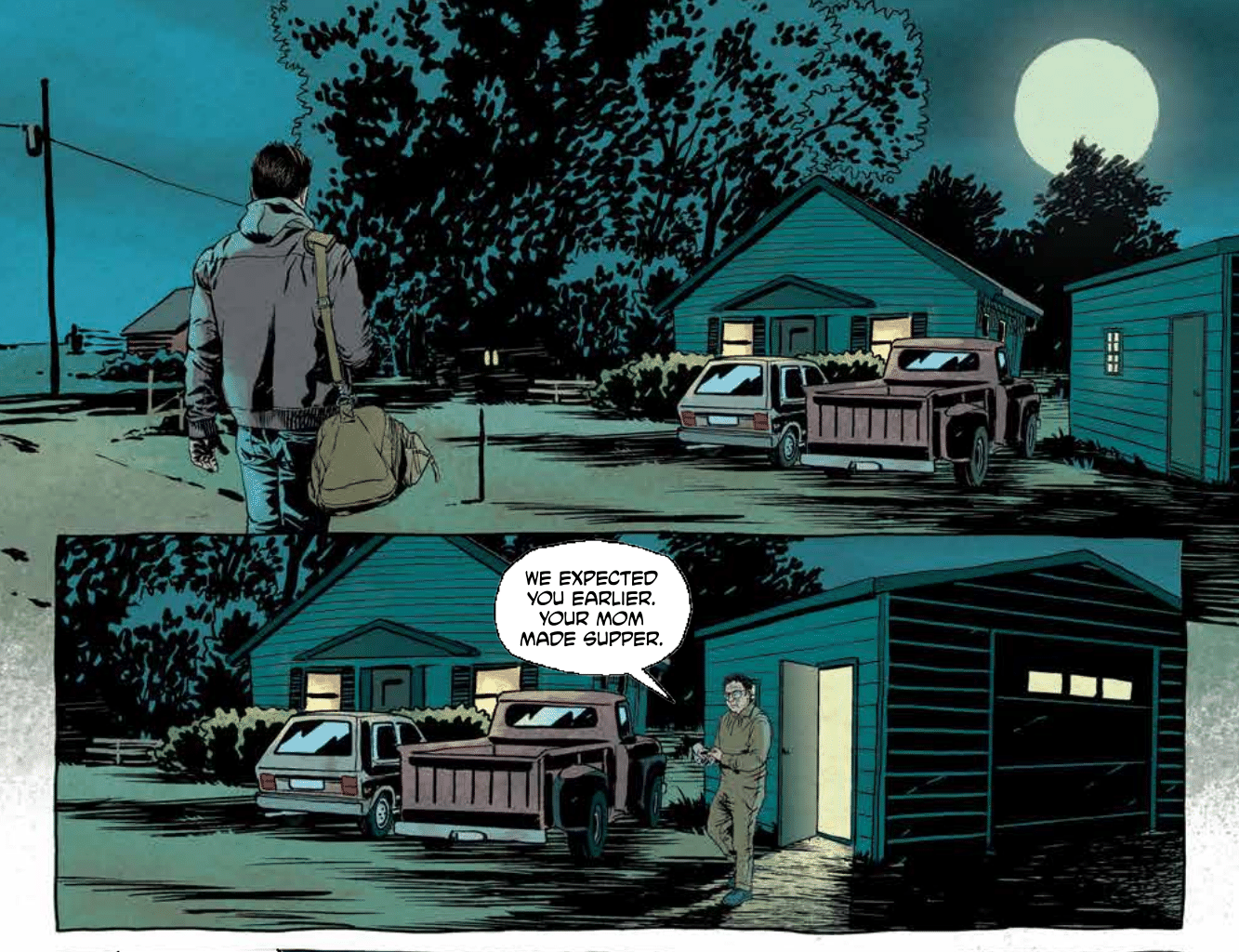

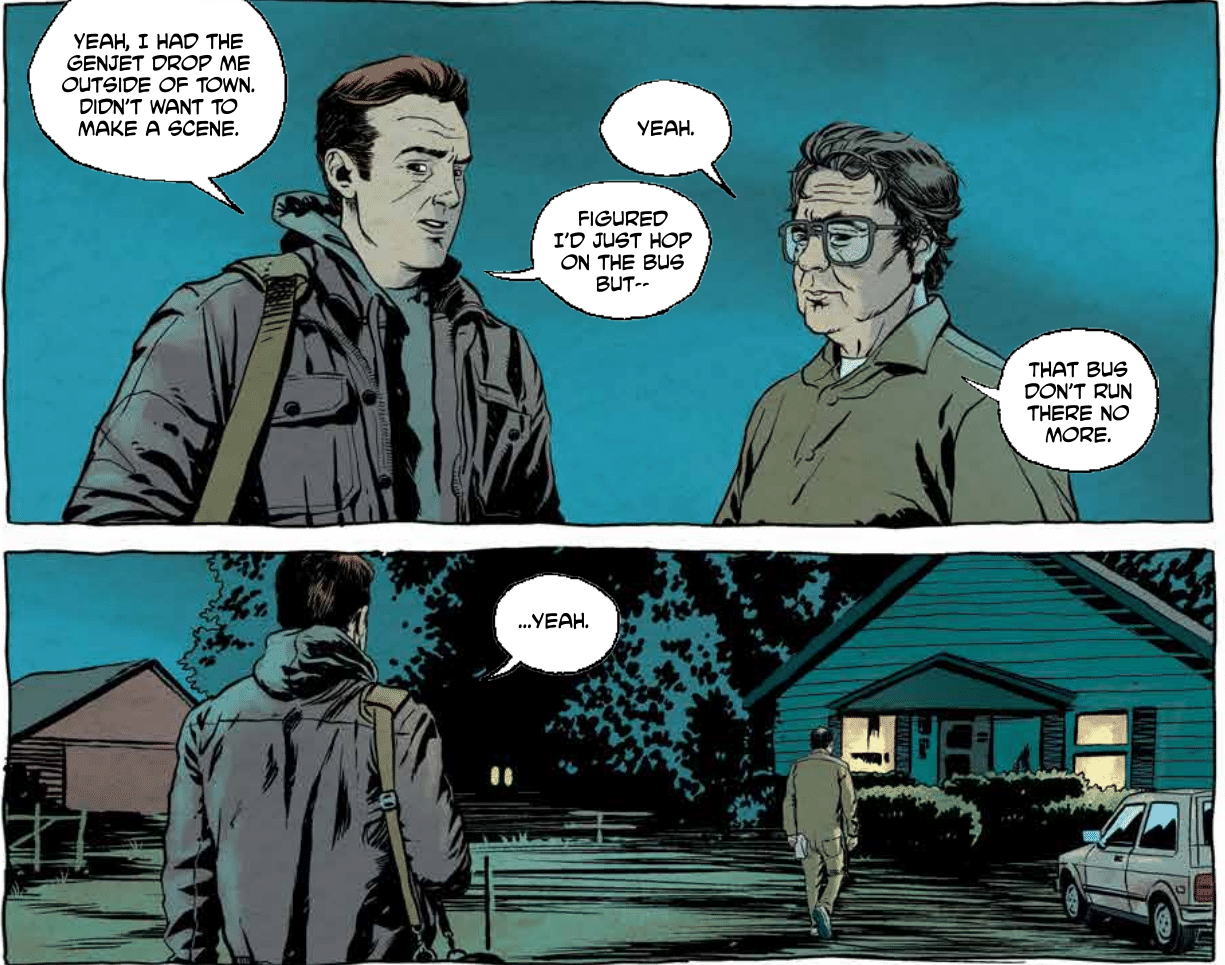

KAK: A theme of “Local Man” is people leaving their hometown to pursue bigger dreams and opportunities. But when problems arise, they return home feeling like failures. Why did you want to explore that?

TS: Honestly, because it’s my nightmare. I grew up in Ringle. It’s a lovely town, a great place. But there was nothing for me. I’m a creative by trade, and there’s obviously not a lot of jobs for people like me in places like that. So, I had to leave to do anything. A big part of it was when you leave your town — to justify it for yourself — you have to feel like you’re angry and you’re punk about it.

Then, you tell everyone, “I’m going to go do this, and that’s why I’m leaving. I’m leaving my family and my high school girlfriend,” and all these sorts of things. Then, if you go and try to do those things and you fail, it’s like you’re admitting that even though the other parts of the world had something for you, you couldn’t take it. Just for me, it’s just this nagging fear in the back of my head that I’d have to crawl back and sit at the bar in Ringle and admit I couldn’t hack it.

As much as I loved being in those places and having left, now I can’t go back. I’m a different person. I’ve lived in Chicago for 20-some years. It’s just the difference of what you become, and we play with that in the book, too. (The main character) Jack is not the same guy. He’s lived a different life. He struggles to relate, especially to his parents and to the people he used to know. They all hate him, too, which I hope wouldn’t be a problem when I went home. But that’s a big part of our story.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.