Over the weekend, the Islamic State group claimed responsibility for two car-bomb explosions that killed 39 in the city of Homs, Syria. The bombings are the fourth to have taken place there since December.

Fighting between the rebels and government forces erupted in Homs starting in 2011, and the city has functionally been a war zone ever since. The city has seen destruction on a massive scale, and an almost equally large exodus of its residents.

But within the destruction, many people are trying to live their lives and stay connected to the place they call home. No one embodies this spirit more than Marwa Al-Sabouni, a Ph.D. in Islamic architecture who runs a private architectural studio in Homs. She has seen buildings she created reduced to rubble, but she and her husband refuse to take their children and flee.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Al-Sabouni says that while she knows it is risky to stay, she has no plans to leave.

Here’s more of her interview with Anne Strainchamps:

Anne Strainchamps: As an architect, when you look at how much has been destroyed in Homs right now, do you think, “This city is dead. It can never come back from this level of destruction.” Or do you think it can be rebuilt?

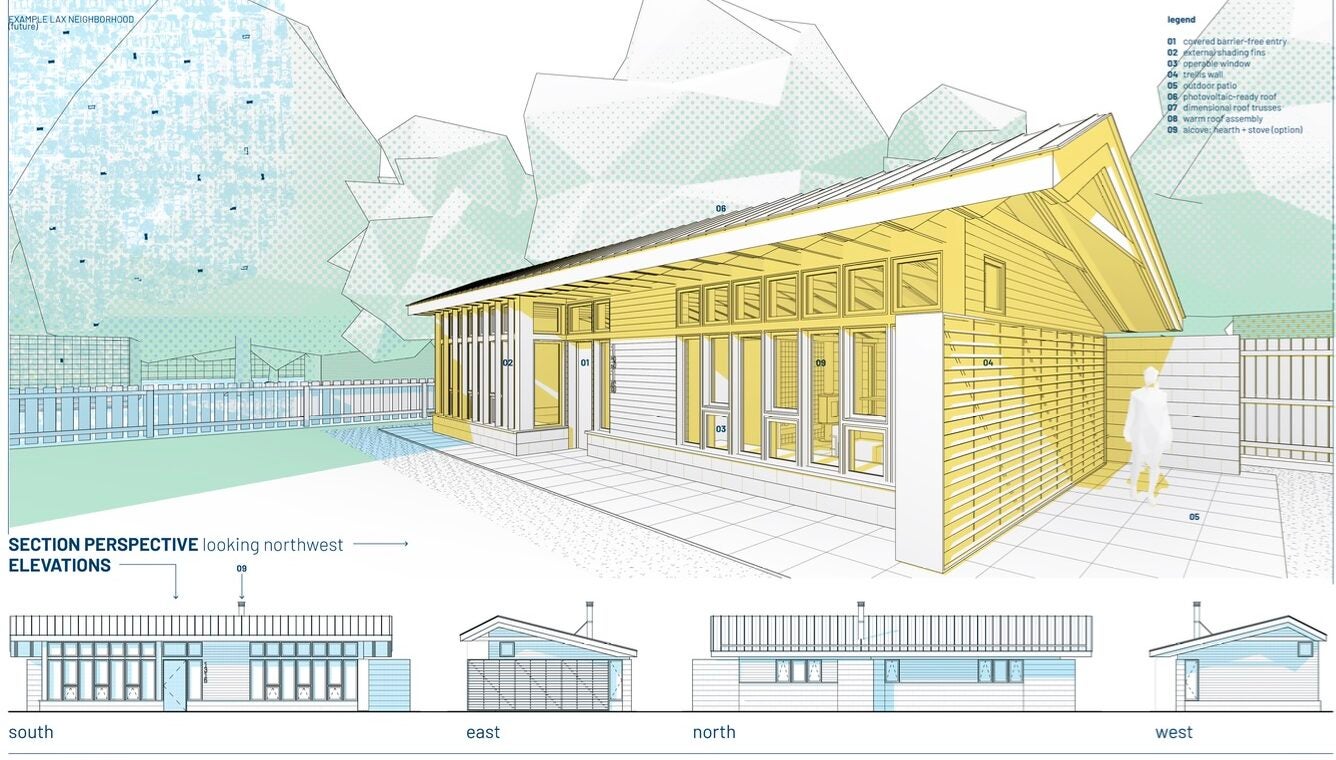

Al-Sabouni: Nothing is impossible. Cities are destroyed for several reasons. Maybe an earthquake or hurricane or whatever, but as long as there are people who believe in this city or believe in their existence, there should be hope to rebuild the city. It should be their hope. So as an architect, I see there is hope. But we should be very very careful where to start and not to make the same choices we did in the past.

Homs was historically one of the great, famously diverse Middle Eastern cities. It was a city with both churches and mosques — a place where people of different faiths and backgrounds lived and worked together. In your book, “The Battle for Home,” you make the case that some of that tolerance eroded in the decades before war actually broke out, in part because of urban planning and architecture. Can you give me an example of what you mean?

In the New City of Homs, there is building just for building’s sake without any consideration for beauty, for value, for identity. Those concepts are out of perspective. On contrast, in the Old City, those values were cherished and cared for. What I’m arguing is that the reason we lived in harmony was because of the moral values built into the urban fabric. The identity that springs from these architectural choices is what made us live in harmony, so when I talk about what is wrong — these concrete buildings, ugly things without any consideration of aesthetics — you can witness they are just made for making money. It’s just a box to put people in.

So the destruction of Homs began long before the shelling started.

Yes. Long before that.

I’m thinking that living in the Middle East, you’ve grown up surrounded by buildings that have stood for centuries. Churches and mosques that have seen generations and regimes come and go. And now you’ve seen so many buildings, some of which you designed, destroyed, does that change how you think about buildings? Do they seem either more fragile or more sacred to you now?

I think that people are more important than buildings. I think we can recreate their history. We can recreate those buildings. Now I see buildings as less important than I’ve seen them before. I’m talking about ancient buildings. It doesn’t hurt me as much as seeing children or innocent people going through suffering. That hurts me a lot more than seeing a building being destroyed.

I keep thinking that you’re raising your children in this destruction. How do you talk with them about it?

Frankly. Very frankly, very openly.

You must try to help your children deal with the fear, the terror of annihilation, which is what’s so scary about seeing all that destruction. Is there anything you say or talk about with your children to help them survive inside as well as outside?

It has been difficult and it is still difficult. Every stage has had its own problems, and we had to come up with ways to deal with it. Like when there was shelling and bombing, my little one was very scared and we had to reassure him over and over again that this is your place, and this is where the bombing is happening. You have to answer why people are killing each other. You have to be very careful and frank as much as you can. I break it down for them piece by piece, I think. And they have grown, all the children. This is the generation that has witnessed so many ordeals and they have grown up very quickly, and they are like old people inside young bodies. It’s a shame, but this is their reality, unfortunately.

Do you think they’ll want to leave, or will they want to stay in Homs when they grow up?

I hope they won’t leave. I hope that we have set, as parents, an example to stay and fight and do the best you can in the moment you are in and the situation you are in. I hope this message has reached my kids.

There’s a line in your book I really love. You write, “to destroy one’s home should be considered a crime equal to destroying one’s soul.”

When you take everything from a person, like his home — the memories, the moments that you’ve lived inside the home and the amount of effort you put in to build a home, it’s incredible. So when you lose your home, you aren’t just sad for the material things you’ve lost — you are sad for those little things. People will share their sorrows of their photos blowing in the street. When you enter your place and see the place you used to sit or the place you used to eat with your family and all this is destroyed, it’s very… it is a crime. It is a crime as I see it, because it’s devastating for them. And I’ve witnessed the amount of pain that this has caused folks.

We’ve talked a lot about destruction and loss. I’m sure there are still moments of beauty. I’m sure there are still things in Homs that are beautiful to you and fill your heart with gladness. Can you tell me about one thing that still makes you happy?

Frankly, I can’t think of one.

I’m so sorry.

Me too. But hopefully there will be again.