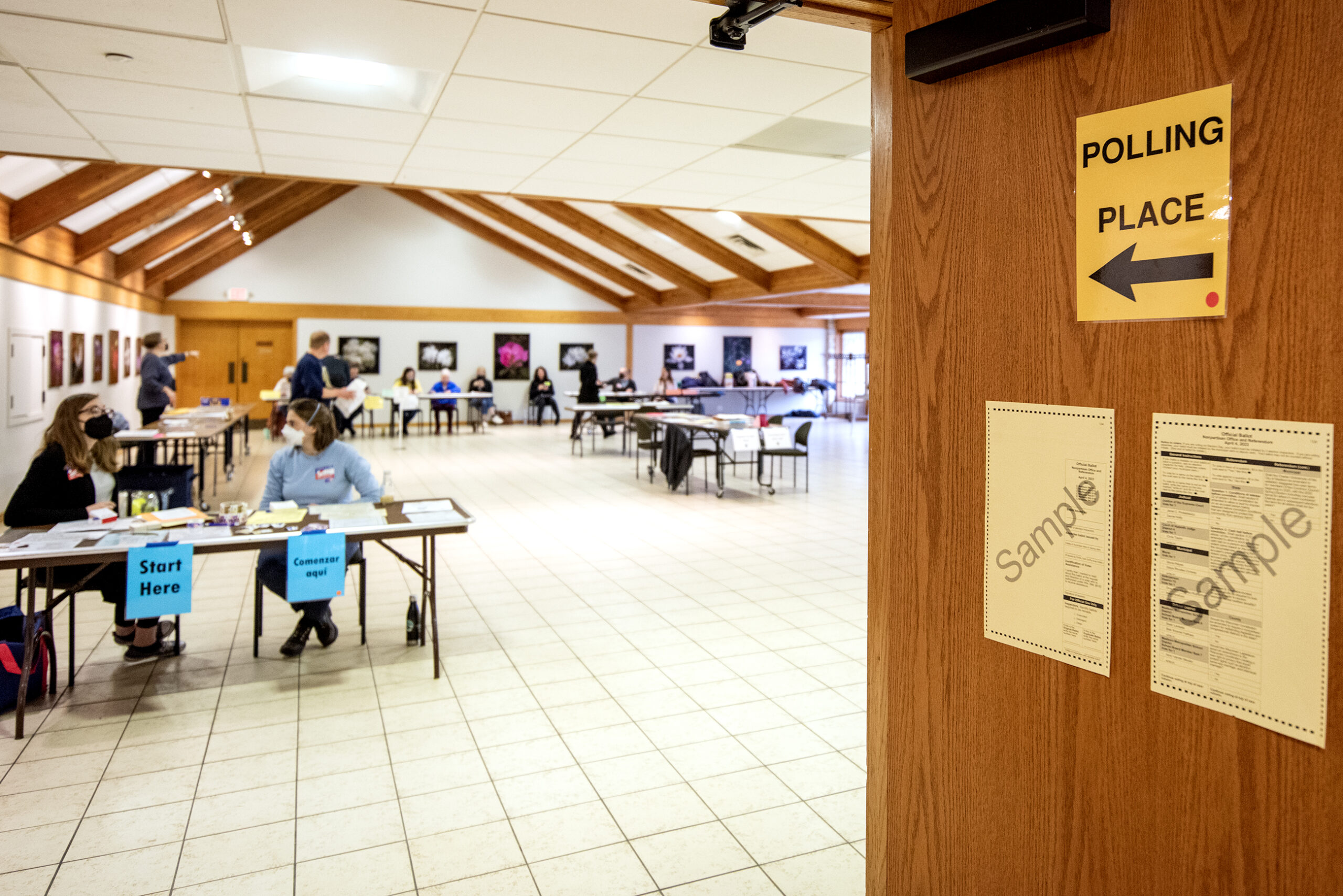

Election workers’ identifying information would be less available to the public and attacks on those workers would be punished more severely under a proposal circulating through the state Capitol. The bill’s authors describe it as an attempt to protect civil servants from harassment, doxxing and attacks.

The bipartisan bill would exempt many records with identifying information about poll workers from being accessed publicly, and also make it a felony to physically harm an election official or worker.

“The purpose of this bill is to provide safeguards and protections for our state’s hardworking election officials,” said Rep. Joy Goeben, R-Hobart, a coauthor of the proposal. “We want them to feel safe while conducting their duties. They deserve to do their job without fear for their personal safety or their job security.“

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The bill would also extend whistleblower protection to election workers who report concerns about impropriety in elections. Election workers who report what they “reasonably believed to be election fraud or irregularities” would be protected from employment consequences, such as discipline, demotion or termination.

Members of the Assembly Committee on Campaigns and Elections debated and took public testimony about the bill on Tuesday.

The proposal comes in the wake of the 2020 election, when unproven accusations of election fraud were leveled against election workers across the country, but especially in competitive swing states like Wisconsin. Workers have reported harassment, including death threats, and the Department of Justice has investigated hundreds of threats.

According to a recent survey by the Brennan Center for Justice, almost a third of election workers say they have experienced threats or harassment because of their job, and turnover rates are significant going into the 2024 election.

Democrats on the committee raised questions about the whistleblower clause, including how to define an election worker’s concerns as “reasonable.”

“I worry a little bit because there definitely was a subset of individuals who had a very skewed view of the election, and some things that one person views as an irregularity is actually standard procedure,” said Rep. Lee Snodgrass, D-Appleton. “I also don’t want a bill in place that’s going to open up to a lot of unfounded claims.”

Goeben said she thought election workers are well-trained, so that many concerns they would share would be well-informed.

“It’s pretty easy to double-check certain things. People sometimes are misconstrued of what the rules might be, and then it’s pretty easy to have a learning moment,” Goeben said.

Edgar Lin, an attorney and Wisconsin policy lead with the national group Protect Democracy, testified that attacks on election workers take place regardless of an official’s political identity or where they live.

He raised questions about the whistleblower protections, saying that election workers should have a clear reporting process for sharing concerns.

“Without a clear process a whistleblower event regardless of merit could descend into chaotic litigation, which is why clarity matters, and that could further undermine the confidence in our election system,” Lin said.

Lawmakers on the committee also moved forward three bills that would prevent municipalities from closing polling places within 30 days of an election, unless specific conditions are met, require the state Elections Commission to reimburse municipalities for some costs during some special elections and require communities that broadcast election canvasses to retain a recording of those broadcasts for 22 months. Those bills received bipartisan support. It is not yet clear whether they will receive votes by the full Assembly.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.