Wisconsin schools saw a marked increase in chronic absenteeism last school year and a slight dip in overall attendance rates.

Attendance rates dropped to 93 percent last year, after hovering right around 94 percent in the three preceding years, according to data released this week by the state Department of Public Instruction. Rates of chronic absenteeism, when a student enrolled for at least 90 days and attended less than 90 percent of the days, jumped from 12.9 percent to 16.1 percent.

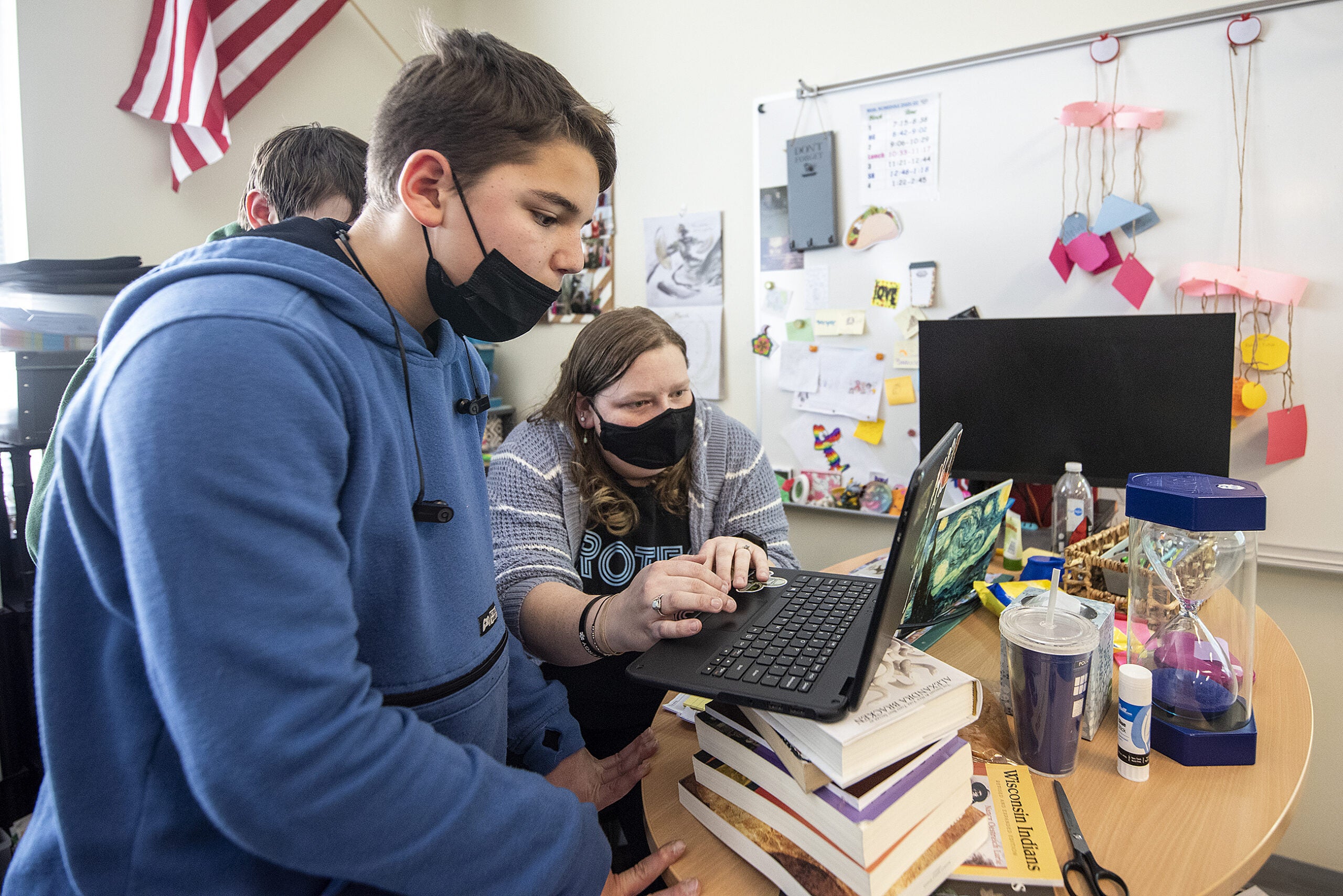

“Kids really start to feel like they don’t belong anymore,” said Nathan Hanson, superintendent of White Lake Public Schools in northeastern Wisconsin. “It’s all tied together — missing that time hurts academics, it hurts social-emotional well-being.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

White Lake’s attendance rate last year was 88.5 percent and chronic absences were 53 percent, according to DPI’s data. The actual rates are lower, Hanson said, because school staff didn’t realize it should mark students who were going through learning materials at home during quarantine periods as present rather than absent, but he said attendance did suffer last year and chronic absenteeism increased.

Experts say rates of chronic absenteeism might be even worse this school year.

Hedy Chang, head of the nonprofit Attendance Works that’s focused on closing equity gaps by increasing attendance, said she has seen chronic absence rates double and even triple in some places compared to their pre-pandemic absences. Some of the increase over last year might be because of virtual learning, which could have lower attendance standards — logging into a website, for example, or opening a Zoom call.

“What everyone hoped was that when we came back to school this current school year, that because everyone was so excited about seeing everyone in person, that we would see this enormous increase in attendance as well as engagement, and really start to be able to recover from this pandemic,” she said. “This year was not what we all hoped for.”

Hanson and principal Jeff Neufeld in White Lake said they’ve had more chronic absences this year than before the pandemic, and they’re expecting that rate might continue to rise. Even before the pandemic, attendance rates tend to get a little worse in the last term of the school year, they said.

So far, for the district, 23 percent of students are chronically absent and attendance is at 91 percent.

Neufeld said the legacy of at-home learning and COVID-19 disruptions are hard to shake, especially in children who haven’t yet had a normal school year. He said he has been working with one first grader and her family on attendance issues.

“I am seeing separation anxiety, especially on Mondays, being separated from Mom — and I can see that from Mom as well,” Neufeld said.

Chang said it’s also hard to get students who could show up to school last year by opening a computer and logging on back into the routine of waking up early, getting ready, and getting to the physical school buildings.

“That takes practice, and people were out of the routine,” she said. “Then, not only was it difficult to establish it, but then you had quarantines and COVID constantly getting in the way of establishing that regular routine.”

Chronic absence and attendance issues can have long-term effects.

Low attendance rates in early grades correlate with lower reading proficiency by third grade, lower academic performance in later grades, and a higher probability of dropping out of high school. It’s also linked to higher rates of suspension in middle school.

Absences also tend to build on each other as the longer a student is out of the classroom, the harder it can be to readjust. Hanson said he has seen that in White Lake.

“When you look at kids who are chronically absent, they feel it’s harder to get back in that classroom,” he said. “They’re behind, their peers are ahead of them, they don’t feel as smart, they haven’t had the social interactions for a few days that their peers have had, and they’ve got to work their way back into that.”

Hanson said it’s also falling unevenly. Some entire classes had to quarantine this year because of COVID-19 exposures, and he said they seem to be struggling more with absences than those that weren’t quarantined.

Absences and low attendance rates are symptoms, said Chang. They might mean students are struggling with health care, transportation, disciplinary issues or a lack of engagement — maybe because they’ve fallen behind on academic concepts, or maybe because they’re too far ahead and aren’t feeling challenged.

“The absence itself doesn’t tell you what the problem is or what the solution is, it just tells you that you need to take a harder look,” she said.

To Hanson, that means everyone needs to step up — schools and school families, but also community members.

“This is going to take education years to recover from,” he said. “This is going to really take an effort on the part of our society to get this back where it should be, and working together to get kids back in school.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.