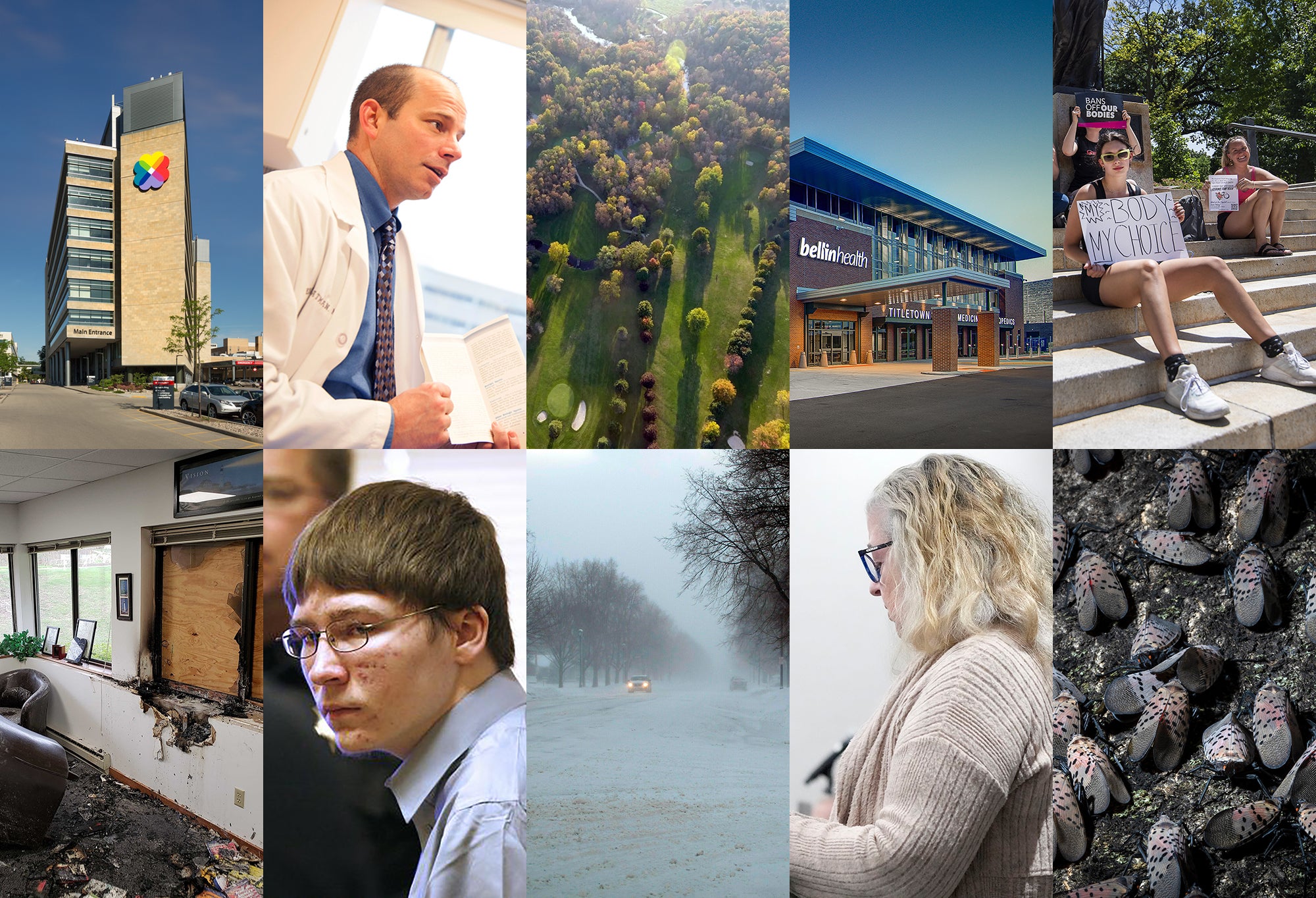

Brendan Dassey of the Netflix documentary “Making a Murderer” continues his quest for clemency, now with the backing of the lawyers who represented his uncle, Steven Avery.

On Wednesday, attorneys Dean Strang and Jerry Buting issued an open letter to Gov. Tony Evers highlighting the alleged injustices in Dassey’s case and urging the governor to commute Dassey’s sentence.

“The courts have failed Brendan repeatedly and at every level,” the letter said. “We ask you to exercise the power that only you have: to free him. We ask you to do it now.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

In 2007, at the age of 17, Dassey was convicted and sentenced to life in prison for the sexual assault and murder of Teresa Halbach. But the conviction hinged on a confession from Dassey that the lawyers argue was coerced and untrue.

Dassey, now 32 and currently incarcerated in Oshkosh, has spent nearly half his life in prison for a crime many argue he didn’t commit. He is not eligible for parole until 2048, when he will be 59 years old.

His 2019 petition for clemency was denied because he was ineligible for a pardon and Evers refused to consider a commutation, the shortening of a sentence.

In their letter, Strang and Buting call out Evers for not fully exercising his constitutional power of executive clemency. While Evers has granted numerous pardons — vacating convictions after a person has served their time and been released — he has never commuted, or shortened, the sentence for someone still incarcerated.

“We’re urging the governor to start using that power, using it judiciously and fairly with mercy not just in Brendan’s case but in many other deserving cases,” Butin said in an interview with Wisconsin Public Radio.

And it could help fulfill Evers’ campaign promise to reduce prison populations in Wisconsin, the attorneys argue.

“The criteria that he’s established is that you have to be basically out of prison and off any supervision for five years before you can even apply, which of course, does nothing to reduce incarceration,” Buting said.

While Buting and Strang do not represent Dassey, they were moved by the 16-year anniversary of his “manipulative interrogation” to speak out on his behalf.

“When it’s a matter of justice, it applies to all of us. You know, it affects all of us,” Butin said.

Dassey was 16 when he was first brought in for questioning in 2006. According to a statement in the letter, police falsely told Dassey they would charge him unless he helped “fill in the gaps” left by his uncle, who was convicted in Halbach’s murder. In return, police told Dassey they would protect him.

According to the statement, no adult was contacted before questioning began and no adult was present on his behalf.

In 2016, a federal judge in Milwaukee found “significant doubts as to the reliability of Dassey’s confession” and demanded his release and retrial. But the order was overturned in a 4-3 vote.

Dassey’s story is the subject of numerous articles, websites, episodes, podcasts and billboards, largely focused on wrongful convictions.

Melbourne mom Tracy Keogh runs a site dedicated to Dassey’s release. She was inspired to get involved when she watched the Netflix documentary and felt an instant connection to the vulnerable young Dassey who, despite being 16 years old, was functioning between the ages of 9 and 11. Keogh said this created an uncomfortable power dynamic between Dassey and his interrogators.

“You understand what you’re watching is wrong,” Keogh said. “There was no adult in any of those situations that was there with Brendan’s best interests. You know, he had no protection. And he had very little understanding what was happening to him.”

His case has led to legal reforms, including new laws in Illinois and California on police interrogation and children, and requiring attorneys to be present when children are being interrogated. Dassey’s videotaped confessions are even used to train police officers how not to interrogate kids with special needs, the press release said.

Despite these steps forward for juvenile justice, Dassey remains in prison. The United States Supreme Court has refused to hear Dassey’s case, so he has exhausted his judicial paths of appeal. A sentence commutation from Evers is his only remaining chance.

“Why that (power) has not been exercised by Gov. Evers I can’t say, but I do think it’s time. It’s way past time in Brendan Dassey’s case,” Butin said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.