Actor and environmentalist Ed Begley Jr. talks about his fascinating memoir. Christine Coulson on her novel, “One Woman Show.” It’s told completely through art museum plaques. And author Jeremy Arnold discusses the history of Christmas movies.

Featured in this Show

-

Actor and enviromentalist Ed Begley Jr. reflects on his incredible, socially conscious life

As Ed Begley Jr.’s name indicates, he’s the son of Ed Begley Sr. Like his father, Begley Jr. became an actor. He appeared on “My Three Sons” and Norman Lear’s satirical soap opera, “Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman.”

Begley also starred as Doctor Victor Ehrlich in the 1980s medical drama, “St. Elsewhere.”

He’s appeared in films with Jack Nicholson, Meryl Streep and Christopher Guest. He introduced himself to a whole new audience when he played Cliff Main on the hit drama, “Better Call Saul.”

Begley is also well known for his work as an environmentalist — like the time he drove Annette Benning to the Oscars in a Bradley Electric car. It had gull-wing doors, and she didn’t know how to get out of it.

Begley has lived an incredible, socially conscious life. He’s captured most of it in his inspiring, hilarious memoir, “To The Temple of Tranquility…and Step On It!“

WPR’s “BETA” sat down with Begley to discuss his life and his environmental ideas.

The following conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Doug Gordon: Your father, Ed Begley, was an Academy Award-winning actor, and he worked in theater, radio, film and television. What was it like for you to write about your dad?

Ed Begley Jr.: It was a catharsis because I had many feelings about him when I was young, as we all do with our parents and many negative things. I thought he was a great oppressor. I thought he was many things, but upon a brief reflection just a few years after he passed, I realized he was not. He had his flaws, and I have mine. But he did very well with what he was given in life.

Overall, he was a very good parent and a fine father to my sister Elaine, me and my half-sister, Maureen. It’s like that Mark Twain line: “My father was a complete moron when I was 18. But it’s amazing how much smarter he got when I was 23.” That was true in my case.

DG: You learned some surprising news about your father when you received your birth certificate while getting your driver’s license. Can you tell us about that?

EB: Yeah. Another flaw that he had was the secrecy of the Irish. I got my birth certificate to get my driver’s license. I’m in the back of the car, and I open it up and look at it, and there’s no mother’s name. I thought that was odd. My mother died when I was 7. I couldn’t make sense of it. So, my dad was driving the car. I said, “Dad, why is there no mother’s name on my birth certificate?” Long silence.

Finally, he says, “Well, Amanda wasn’t your mother” — the woman I knew to be my mother who died when I was 7. That was my mother, my sister’s mother. Now, suddenly, she was not my mother. I said, “Well, who was my mother?” He said, “Sandy is your mother.”

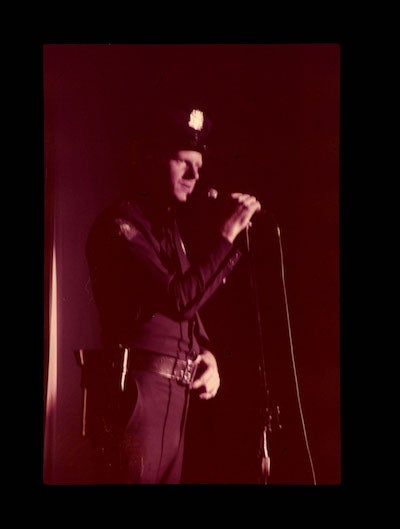

Ed Begley Jr. onstage at the Troubadour in 1975. Photo courtesy of Ed Begley Jr. Then, twin explosions in my brain because this woman, Sandy, was someone I knew well and was crazy about. My sister and I loved this woman. We shared Easter time and got an Easter basket from her. On Christmas, we got a gift for her. We never knew quite who she was, but we liked her a lot, and it turned out that she was Mom.

DG: How did that impact you and your relationship with your father?

EB: It was a significant strain because I had been lied to. I wondered … how could you be that good at lying? Because I was terrible at lying. I was terrible at it. I’d get caught all the time. But how could my dad and everybody else pull this off when we didn’t even know who our mother was? And it was right there in front of us.

It caused me to try to live a life of deceit, in and out of my marriage. And that’s not a good way to have a marriage or a life.

DG: You had this interesting conceptual stand-up routine that you did in which you portrayed a member of the Los Angeles Police Department. Can you tell us about that?

EB: Yeah, drug humor was very big in the early ’70s, so I had this character called Officer Ed Begley. And the routine was, I’d go to a club like the Troubadour, the Bottom Line or Max’s Kansas City or the Icehouse, and I’d have the sound guy introduce me: “Good evening. Before we begin with our show, Don McLean will be out in a moment. We have a man from the Los Angeles Police Department here to talk to you about some of the problems in the community, specifically drugs. Welcome, please, Officer Ed Begley.”

The people would begin to boo, understandably. They’d paid to see a musical act, and there’s some warm-up act, and now it’s going to be the LAPD talking to them about drugs. But the people that booed the loudest would be laughing the loudest in a few minutes because I would start very real, and by the book, as an LAPD officer, then I would get more and more absurd. It was a very popular routine in the ’70s.

DG: Besides your acting work on TV and in film, you’re also known for your environmental activism. What made you decide to devote time and effort to that?

EB: It was simple. I was raised in Los Angeles. I spent 20 years in smoggy L.A. I got a brief reprieve during the school year portion; I’d go back to Long Island to go to grade school. But finally, in 1963, I moved to L.A., where I was born, and spent a lot of time in L.A. only. So, I was breathing, 365 days a year, that horrible smog. And it seared your lungs. It just hurt to breathe or to play.

So by 1970, they discussed doing something for Earth Day. They would talk about cleaning up the air. And I went, “sign me up,” because I knew we had dirty air.

And here’s the good news. Even though we have four times the cars in L.A. since 1970 and millions more people, we have a fraction of the smog. We’ve done much of the work, and more importantly, proven that we can do it.

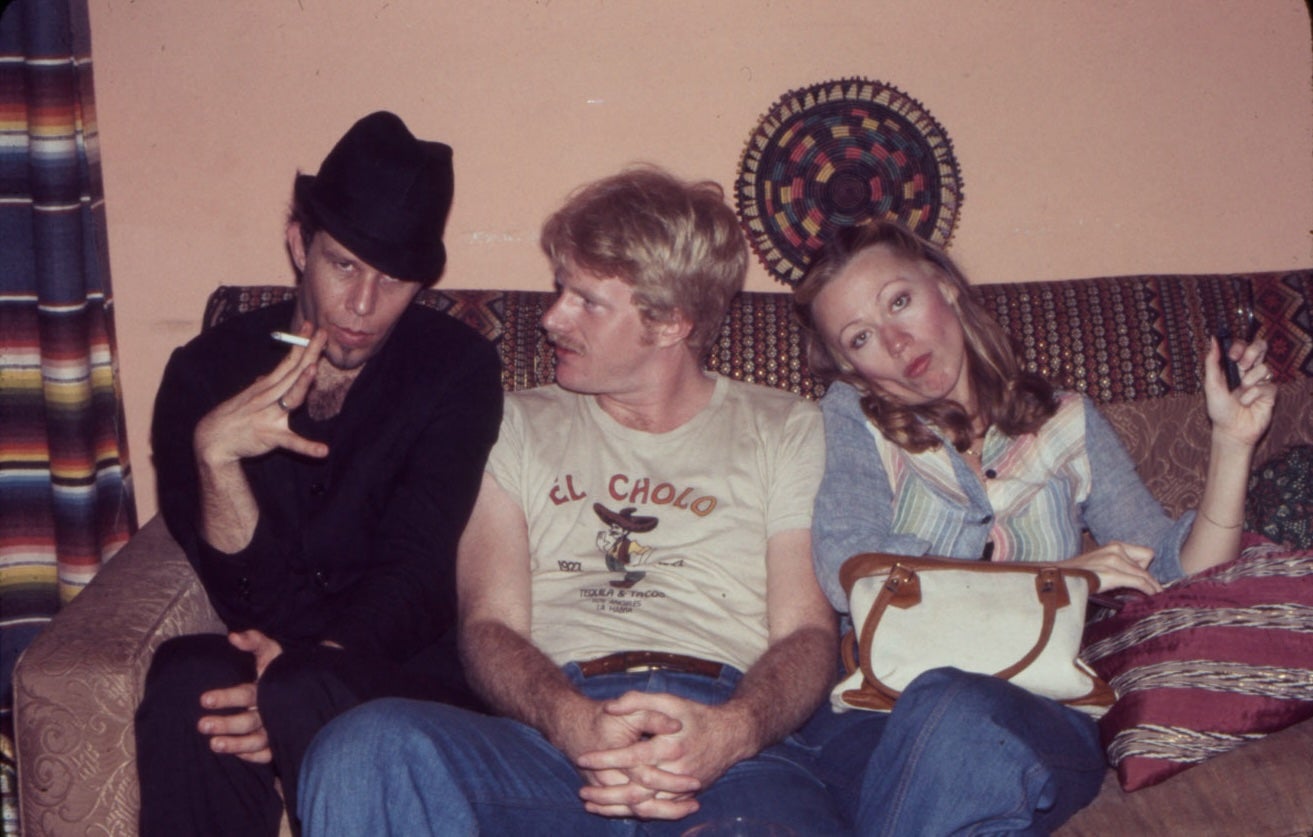

Tom Waits with Ed and Ingrid Begley, 1977. Photo courtesy of Ed Begley Jr. DG: During the ’90s, you got fewer acting roles than before. Do you think that resulted from your efforts to save the environment?

EB: My agents and managers at the time felt it was a factor. I was not on a do-not-hire list. I think I gave people the creeps. They thought I would preach to them or point at them as they pulled up in their limo or SUV and say, “You shouldn’t be driving a car like that. You’re killing everybody.” But I don’t operate that way at all. I do what I do. And if other people want to try it and join me, that’s fine.

Eventually, Chris Guest bails me out of movie jail and puts me in “Best In Show.” And I’ve been working ever since.

DG: That was a significant turning point, when Chris Guest hired you?

EB: Yeah. In the ’90s, it was slim pickings for studio movies. I did two studio movies the whole year. I was in “Greedy,” in that wonderful movie, and then I did “Batman Forever,” another fine film. And finally, as you say, Chris Guest was my salvation.

DG: You had the opportunity to work with Michael Richards, who, of course, is most famous for playing Cosmo Kramer on “Seinfeld.” And on the flip side, he had the opportunity to work with Ed Begley Jr. What was that experience like?

EB: I just tried to keep up with Michael. He was the most talented guy at Valley College, where I studied. I was working at a whole other lower level of acting than he was. One night, he was fooling around in front of a bunch of people, and he summoned me up with him before the group. And I started to work with him in an ad-lib sense, but I didn’t have my head on straight. I couldn’t keep up with Michael.

You know, neither of us knew the rules of improv. We thought we had invented it. Look what we did. And there are rules to improv; you’re supposed to always agree. If somebody says, “I’m the king of England,” you’re supposed to say, “Yes my liege.” So we didn’t know any of that. Avery Schreiber came and watched us and tried to give us some guidance, but I wasn’t ready to hear it. So Michael went off and joined the Army.

DG: You were diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 2016. If you don’t mind my asking, how are you doing these days?

EB: I’ve had it since 2004. My life was so healthy, I didn’t even know I had it for 12 years. In 2016, I was finally diagnosed. But that was seven years ago, and so many people have had it for that time, and they’re debilitated, but I’m not. So I’m one of the lucky ones.

-

Author’s new book tells the life story of Kitty Whitaker through museum wall labels

I don’t know about you, but whenever I go to an art museum, I like to read the descriptions of the art. Sometimes those wall labels help me understand the piece, and sometimes they don’t.

Christine Coulson spent many years writing these various labels for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This gave her the idea of trying to describe people as works of art.

And then — Coulson being Coulson — she took this idea a step further. Actually, she took it several staircases further. She decided to write an entire novel in the form of museum wall cards. The result is “One Woman Show,” an incredibly immersive and innovative read.

The following conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Doug Gordon: Christine, what inspired you to write a novel in the form of the museum exhibition plaques?

Christine Coulson: Well, I worked at the Metropolitan Museum of Art for 25 years, and one of my last projects there was to write the wall labels for the new British galleries that opened in 2020. And it was while I was working on those galleries that I had the idea to write labels about people, to treat them like intricate works of art.

DG: How did you decide to focus on the life of one specific person, Kitty Whitaker?

CC: That’s important because I did not plan to write a book about Kitty Whitaker. I had the idea to do this, and then I let it cook for a while, almost a couple of years, which I quite like to do. I like to kind of withhold ideas and go visit them and specifically don’t write them down.

So it was cooking for a while, and then it came to the point where I really had to just try and write a label about a person. And I randomly picked a woman standing in the museum’s galleries, a kind of typical patrician Park Avenue lady. And I wrote the first label, which is actually still in the book. It’s about three quarters of the way through, and I had no particular investment in that character.

I called her Kitty and eventually she kind of took over the book. This was not a linear writing process. I didn’t start in 1906 and then write through a century of her life. It was more of a test to me as a writer to try this idea. And once I had that first label about Kitty, I thought, well, maybe I should try and write 20 labels about her. And I just started thinking about moments that I could capture.

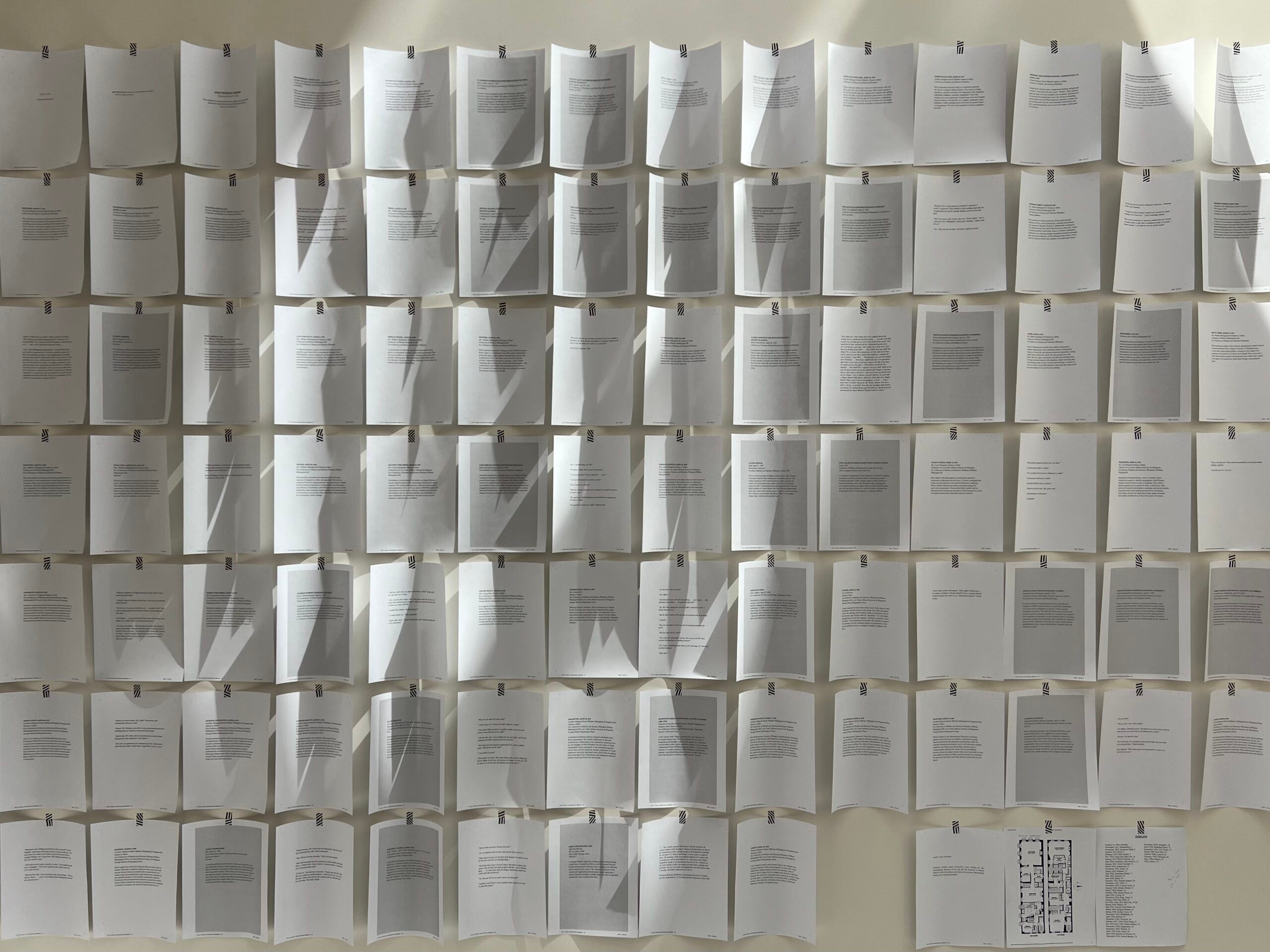

I write on this big wall. So every time I write a label, I tape it to the wall. And so the story kind of spread like an inkblot as I populated this life with these moments to eventually create a kind of retrospective exhibition of a single person.

A sample of Christine Coulson’s wall writings. Photo courtesy of Christine Coulson DG: Your original idea of doing multiple people would still be really great. But I think you really nailed it by just focusing on one person.

CC: Right. And you get the other people in there the way you would in a retrospective exhibition where the curator shows you comparative material.

So in terms of museum approach to looking at this life … there’s a lot that Kitty has in common with the works of art we evaluate and critique all the time. She’s treated that way from her earliest childhood throughout her life. She’s kind of collected and prized. And so that ability to extend that treatment to her and then have to include other people around her in order to give her context is a very typical museum approach.

DG: I’m curious about your creative process. Did you figure out what Kitty’s life had been like before you started writing the novel, or did you make decisions as you wrote? I believe it was the latter, right?

CC: Yeah. As I wrote, I was also really trying to stretch the form. Label writing is very specific. You only get 75 words. There’s a certain voice. Every word has to work. There are no throwaway phrases. So I’m working within a form.

But then I’m also trying to write a traditional novel that needs things like plot and character development and emotional connection. So as I was piecing it together, I was kind of aware of those two things working simultaneously, and I was trying to stretch that form to its greatest capacity. You know, how could I write a funny label? Could I write an emotional label? Could I write a sexy label? Like, what can you really do with this kind of constraint? How far can you push it?

DG: And you pushed it as far as it could go. Maybe even further. It’s such an innovative idea. It’s got what adman Rosser Reeves called USP, the Unique Selling Proposition, because I don’t think there’s any other novel like that. When you came up with the idea, were you worried that this was such an original idea that people might not be able to understand it?

CC: I was worried if it was sustainable. I was worried if it could go beyond just being clever. So I had a lot of readers as I wrote this, particularly in the early stages, both art people and non-art people, to see whether it could be carried and that they could keep up with it and that they really wanted to turn the page.

The strategy of the book is really kind of the opposite of what you experience in the museum, where you look at a work of art, and then you read a label to explain it. Here, I’m giving you the label and every label is opposite a blank page. And so it’s like the job is for you to conjure what I’m describing. So it’s more like label as catalyst rather than explanation.

I love the kind of pulling the reader in in that way and making them complicit in the storytelling. I mean, that happens all the time, even in traditional novels. If you describe a battle scene or a dinner party, you’re making that image as you read. But this actually formally shows you what that’s like. It’s like a metaphor for reading, which I really love. That blank page is very powerful.

As you conjure Kitty, I never describe what Kitty looks like. I never describe what she’s wearing. I want you to make Kitty and make it about what’s happening to her and how she feels about that and what the context is for that. So I love the idea of pulling the reader in that way. And that’s what I had to make sure worked.

DG: The early wall labels contain the line “collection of Martha and Harrison Whitaker,” Kitty’s parents. In this context, the words “collection of” made me think that Kitty’s parents were objectifying their daughter. Did you intend for the reader to have that thought, or am I totally on the wrong track with that idea?

CC: Oh, I think you’re right. I think you can tell Kitty knows she’s being watched from the very beginning. I mean, she understands and I kind of liked that. Actually, she’s very aware of what she’s going through. She’s very aware of the competition involved in the goal of marrying. This is 1906 when she’s born. So these are early days. Some of this hasn’t changed. But I found that the ability for Kitty to simultaneously participate in this societal practice and be aware of it and manipulate it when she needed to was important to kind of give her some agency.

DG: Very well said. You wrote an essay for ”The Daily Telegraph” in which you said that you’re not sure we need museum labels. And that seems to me like kind of an act of self-sabotage, considering your latest novel and your 25 years writing for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Can you explain what you mean?

CC: It’s less anti-label than pro-looking. I’m really interested in people exercising the muscle of looking because I think it’s the much more satisfying way to experience a museum. And I think we’re often meant to feel intimidated in museums and, like, there’s something we don’t know. And I think art does the work for us. And if you’re open to it, and you spend some time with it, you’ll get a lot more out of that than any label and 75-word description can give you.

You know, when we ask someone to listen to a piece of music, we don’t give them a 75-word description beforehand. We just let them listen to it, and either they like it or they don’t like it. Or they tap their foot or they have some kind of very human response.

And I think art can be exactly the same way. If you want to read the liner notes, then you can find out about that. And if you want to read the label, you can get some more specifics. But I think actually allowing yourself to respond to a work of art to choose what you’re going to respond to, not what we tell you is important, but what actually speaks to you? I think if something stops you in your tracks, there’s a reason and you should kind of excavate that and find out what it is. And that only comes from just allowing yourself to swim in the practice of looking. There’s great pleasure in that.

-

TCM author Jeremy Arnold explores the movies of Christmases past, present and future

There’s a short, heartwarming scene in the 1989 holiday classic, “National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation” where Clark Griswold, in the midst of another failed adventure, gets locked in his attic. He stumbles across a box of old Christmas movies and enjoys a tearful, nostalgia-laced trip down memory lane.

It’s a small moment that speaks to the power of the Christmas movie. There’s an assortment of classics that resurface every December that can offer the same kind of relief to some of the stresses of the season.

Jeremy Arnold is the author of Turner Classic Movies’ “Christmas in the Movies,” in which he covers “Christmas Vacation” and 34 other timeless and recent holiday classics. He tells WPR’s “BETA” that because the concept of the Christmas movie as a genre is relatively new, it’s hard to pin down a single definition of one.

“All definitions are valid because Christmas movies were never really a genre historically. The label came later with hindsight,” Arnold says. “So, a Christmas movie is really, for any person, whatever they want it to be. Whatever they decide it to be. Whatever they like to watch every year at Christmastime.”

For his part and the book, Arnold defines a Christmas movie as “any movie of any genre in which some aspect of the holiday season plays a meaningful role in the storytelling.”

Arnold notes that the concept of the Christmas movie didn’t really surface until after World War II, when Hollywood started stressing family in a lot of their releases. A perfect example of this is the 1946 redemption film, “It’s a Wonderful Life” starring James Stewart and Donna Reed.

Arnold says that “It’s a Wonderful Life” is still a beloved holiday classic because it runs the full gamut of seasonal emotions.

“This is the one that really engages the full emotional spectrum of the meanings of Christmastime,” he says. “Christmastime for all of us can mean positive things: joy, family, togetherness, love, compassion, positive transformation. But it can also mean loneliness and alienation, cynicism, disgust with the commercialism of the holiday, all those sorts of things.”

“‘It’s A Wonderful Life’ really runs the gauntlet,” Arnold continues. “I mean, this is a film that has George Bailey trying to commit suicide, which is the ultimate extreme end of despair and loneliness, you could argue. But it also has one of the most joyous endings in all of cinema. It’s always more traumatic to watch than people remember because we remember the ending, but we kind of forget about all the heartache leading to it.”

The holiday redemption story featured in “It’s a Wonderful Life” isn’t new. In fact, it’s basically a modern-day take on Charles Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol” — a story about the redemption of the miserly curmudgeon, Ebeneezer Scrooge.

And while Dickens’ classic has been adapted countless times on screen and on stage, for his money, Arnold points to the 1951 British version, starring Alastair Sim, as the best interpretation of it. He says much of his appreciation is because Sim nails both gears of the Scrooge arc.

“He is just perfect as Scrooge, both the, the awful, cruel, uncaring Scrooge and the one who finds love and compassion at the end,” says Arnold.

He also points out that Sim’s casting was not without a bit of controversy.

“He’d been known as a light comic actor, sort of character actor in British films,” says Arnold. “When the British public learned that he had been cast to play Scrooge, there was a letter writing campaign. There was a lot of outrage before the movie was even filmed that they had cast him. But, of course, when it came out, he silenced all of those doubts.”

Another actor who raised doubts when they were cast, although for very different reasons, was Bruce Willis when he landed the lead in the 1988 action thriller turned Christmas staple, “Die Hard.” At the time, many didn’t think Willis’ physique would be believable in besting a building full of terrorists. He, too, proved them wrong.

For years, many have jokingly debated whether “Die Hard” qualifies as a Christmas movie. Arnold leaves little doubt in his definition.

“‘Die Hard’ actually begins as the most common type of Christmas movie, and that is a dysfunctional family trying to reunite over the holidays,” says Arnold. “The vast majority of Christmas movies are versions of that. It just so happens that this family is a husband and wife where the husband is a cop. And as he’s trying to reconcile with his wife, these pesky terrorists take over the building.”

Arnold argues that “Die Hard” takes a lot of the Christmas movie tropes and ports them into an action movie. He cites a lot of winks from the script and director John McTiernan as well. For instance, Bonny Bedelia’s character’s name was changed to “Holly” for the film. And McTiernan shoots the climatic vault seizure by the terrorists like kids on a Christmas morning, scored by Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.”

“There’s even a Christmas song, ‘Christmas in Hollis,’ which is a rap song that Bruce Willis hears in the limo,” Arnold says. “And (Willis) says to Argyle, the driver, ‘Don’t you have any Christmas music?’ And Argyle says, ‘This is Christmas music!’ So, it’s like the movie is saying, ‘”This is a Christmas movie.’”

There’s little doubt about the Christmas bona fides of two holiday classics from 2003, “Elf” and “Love Actually.” Arnold calls the pair of them “cinematic comfort food” that broke a lot of the post 9/11 tension.

“Something similar happened in 2003 that had happened in the mid- and late- 1940s, where after the national trauma that was World War II, Hollywood responded in part by giving us a glut of Christmas movies and movies that had Christmas in them,” he says.

“Love Actually,” while being primarily set in London, specifically mentions 9/11 and the twin towers in its opening monologue.

“We all suddenly felt very unsafe in a way that Americans never really had before,” he continues. “The atmosphere, society, things felt unsettled and insecure. And I think these two movies opened at just the right time to give audiences the feeling of re-connection that they craved.”

Arnold feels that — even though movie audiences have drastically changed in the past 20 years, and that streaming and the Hallmark Channel have taken over a lot of the yule tide offerings — we could be primed for another feature holiday film.

“I actually think the time is very good right now for some enterprising filmmaker to make a Christmas movie because the pandemic was another national trauma and we’re now two or three years removed from it,” he says. “I was actually thinking maybe we’ll get more Christmas movies after this, because this is such a bizarre shift in our lives and our country.”

Episode Credits

- Doug Gordon Host

- Adam Friedrich Producer

- Steve Gotcher Producer

- Doug Gordon Producer

- Steve Gotcher Technical Director

- Ed Begley Jr. Guest

- Christine Coulson Guest

- Jeremy Arnold Guest

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.