Filmmaker Kyle Edward Ball talks about his indie viral horror film, ‘Skinamarink.’ Also, cartoonist Barbara Brandon-Croft. Her pioneering work made her the first Black woman syndicated cartoonist in America. And the Edgar Award-winning crime novelist Jordan Harper on his L.A. crime novel, ‘Everybody Knows.’

Featured in this Show

-

The director behind the experimental 'Skinamarink' on creating a nightmare

Everyone knows what it’s like to have a childhood nightmare. Just as commonly, everyone knows that no matter how deeply engrained the nightmare can be to you, it’s incredibly difficult to describe it to someone else.

Perhaps not so much for filmmaker Kyle Edward Ball. He’s set on raising the bar even further. His film “Skinamarink” aims to recreate the actual feeling of being trapped in a nightmare.

Ball got his start with his YouTube channel that set out to recreate user submitted nightmares. He told Wisconsin Public Radio’s “BETA” that the lack of any kind of realistic budget turned into creative breakthroughs.

“I would use kind of old Hollywood style effects and because I didn’t have access to a bevy of actors, I would have to get creative on how I would tell a story,” he said. “So, a lot of implying action instead of directly showing action. And when we did show actors, there would be very little performance. We would rarely, if ever, see their face.”

Another element Ball used effectively was the use of low-fi audio, like old cartoons.

“I had leaned into the low-fi of audiovisual format as well, and even doing stuff like playing with old time radio and old-time cartoon audios to really kind of help buffer the narrative,” Ball said.

Ball ports this technique into his first full feature, “Skinamarink,” to a disorienting result. The film — named after the famous children’s song — loosely follows two children, Kevin and Kaylee, as they wake up to discover all the windows and doors from their home have been removed. They camp out close to the living room TV that is the source of the cartoons.

“I always went into the intention of doing a style like that, and that’s how I wrote the script and that’s how I filmed it,” Ball said.

One of the cartoons Ball uses is Max Fleisher’s 1936 short, animated film, “Somewhere in Dreamland,” which follows a similar path of a pair of siblings drifting off to sleep. Ball said he first watched the cartoon as a kid when his parents bought an old bargain bin VHS compilation tape that featured it.

“I always remembered because it’s a beautiful little cartoon,” Ball said. “When I wrote ‘Skinamarink,’ I thought, ‘This is a perfect thing to feature because it’s about a little boy and girl, a brother and sister, and it has them fall asleep and go into dreamland.’ What a cool metaphor that I can play with.”

He pairs this creepy sound design with odd-angled, static shots like when your grandparents left the camcorder on a chair forgetting it was still recording. We rarely see or hear the children or the parents. We see feet or shadows. And the dialogue is often garbled and subtitled all resulting in an unsettling effect.

“I want it to feel like a movie that was forgotten and not taking care of,” Ball said.

To achieve that forgotten feeling, Ball adds the hiss and snaps common on old films from the ’70s. He explains even that became a storytelling tool.

“I was even able to do neat stuff with the hiss and hum to even help propel the story,” Ball said. “So even change the volume of the hiss and hum to do something simple like say, OK, we changed location or time has elapsed.”

“Or even do stuff like slowly imperceptibly, lower the hiss and hum as a scene is supposed to be building as far as tension so that the audience is unconsciously leaning into the sound,” Ball continued.

With a runtime of 100 minutes and no break from his aesthetic, the result can feel at times claustrophobic, again mimicking the sensation of a seemingly endless nightmare.

For Ball, it was even more personal. He shot the entire film in his childhood home.

“I went into writing the script with the idea that I would film in my childhood home,” Ball said. “It was great. There (were) other surreal parts, too. Like on the final day, that’s the first time we filmed in Kevin’s room, which was my room growing up.”

“I just had this weird moment in between takes where I’m like, ‘This is weird. I’m filming a movie in the room that I would have dreams as a kid about filming movies. It’s all come weirdly back to this room.’ But it was strange,” he continued.

Ball’s early work on YouTube and the grassroots buzz for “Skinamarink” owe a lot to Reddit. He said the spreading of the word and even the advance leak of the film on Reddit led to a strong word of mouth campaign. Ball stated that the internet may have been his co-director.

“It all comes back to Reddit. I had started my YouTube channel, and it wasn’t really picking up steam until I started posting videos on Reddit,” Ball said. “Before I was even finished the final cut of the film, I had cut the trailer for the movie and posted it on the filmmakers subreddit, and that’s where we got our distribution deal.”

Audience reaction has run the gamut from unsettled to praise to confusion or even to boredom, but there’s no denying the originality of the project. That’s what Ball aimed for.

“I would say for the most part, people said, ‘Oh, it’s uncanny, it’s strange, it’s weird.’ And I can’t be more thankful that people are responding the way that I intended,” Ball said.

“Skinamarink” is now available to stream via Shudder.

-

Barbara Brandon-Croft revisits her trailblazing comic strip, 'Where I'm Coming From'

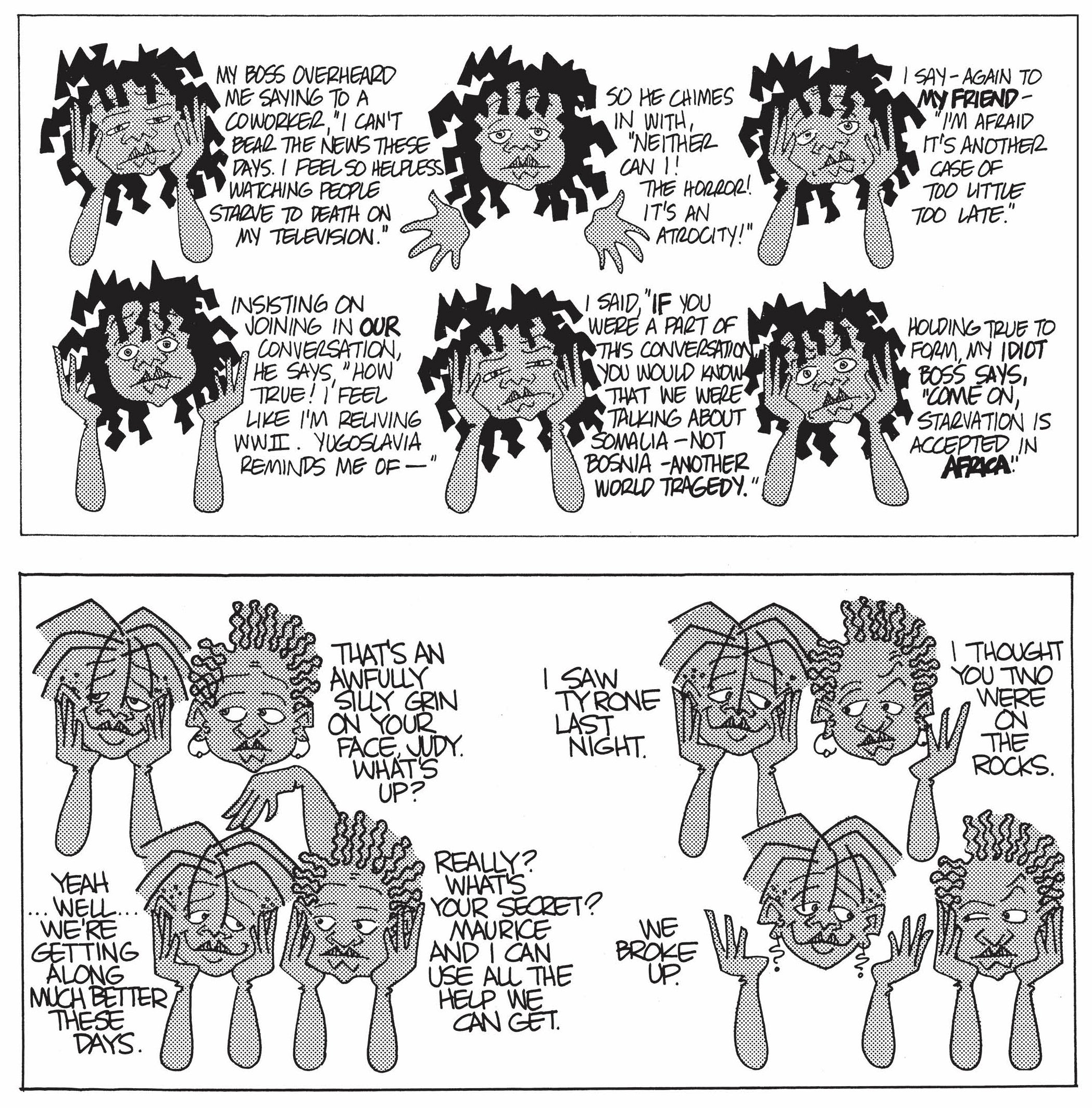

Barbara Brandon-Croft made history with her pioneering comic strip, “Where I’m Coming From,” which ran from 1989 to 2005. The strip features a cast of Black women who talk to one another about social issues that are still relevant today — including gun violence, racism and surveillance.

“Where I’m Coming From” catches the reader’s eyes right away. Brandon-Croft, the first Black woman cartoonist to be published nationally by a newspaper syndicate, only draws her characters’ heads and arms. And these women are not afraid to make eye contact with the reader.

Now, a collection of selected strips from 1991 to 2005 by Brandon-Croft is published in a new book, “Where I’m Coming From.”

Brandon-Croft attended the College of Visual and Performing Arts at Syracuse University in New York.

She created a cartoon feature for Elan, a national magazine designed to appeal to Black women.

“It wasn’t until I tried to get a job at a magazine (Elan) and the editor-in-chief there, Marie Brown, she was like, ‘Well, you’re kind of funny. And you draw. Do you think you can do a comic strip?’” Brandon-Croft told Wisconsin Public Radio’s “BETA.“

“And I was like, ‘Well, sure. I can do it.’ So that’s when it hit me and that’s how I got started doing it.”

Her father’s apprentice

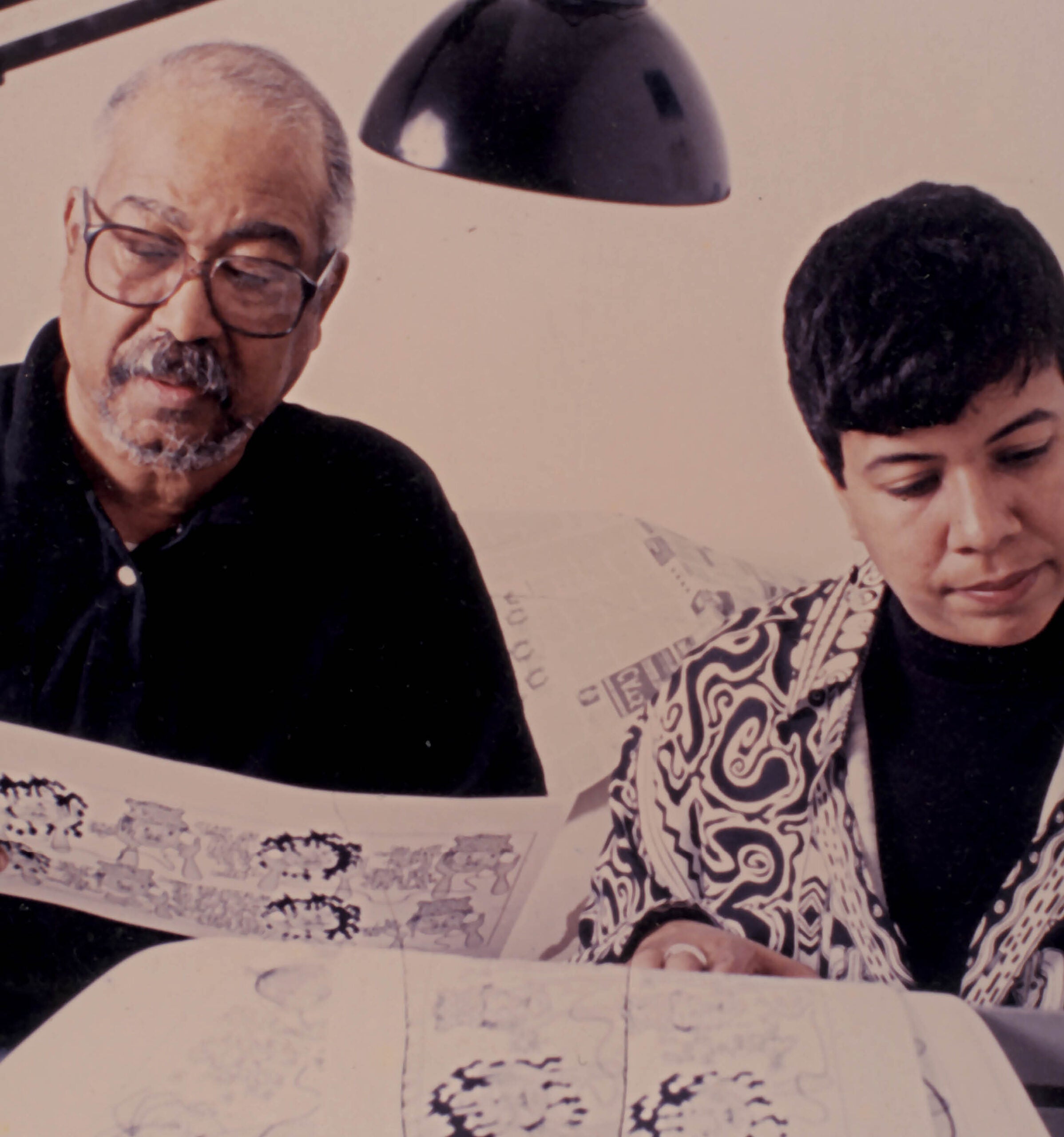

Barbara Brandon-Croft, right, alongside her father, who was also a cartoonist, Brumsic Brandon Jr., left. Photo courtesy of Barbara Brandon-Croft Brandon-Croft was a pioneer. But so, too, was her father.

“My father was a cartoonist. Nobody knows that. My dad is Brumsic Brandon Jr.,” she said.

Brandon Jr. created a comic strip called “Luther,” one of the earliest mainstream comic strips to feature a Black lead character. It was published in the mainstream press from 1969 to 1986.

“So my Dad did a daily. That’s a lot of work,” she said.

Brandon-Croft explained how her father applied Zipatone to his strip for skin tone.

“It’s a sheet of paper that has dots on it or whatever it has on it. And you cut it out and you burnish it,” she said. “And it’s tedious, it’s a lot to do. And he wanted help doing that.”

After helping out her father, Brandon-Croft decided she wanted to create her own comic strip.

“I couldn’t figure out what I wanted to do. But I got stuck on the idea of having Black women talking,” she said. “I was going to have a woman talking to you, and it was called, ‘Where I’m Coming From.’ So in my mind, I was going to have a different character each time. You know, that’s 12 characters a year that I can do. So that’s that’s where it came from. And it seemed to be a good idea.”

Because her father worked in the syndicated comic industry, Brandon-Croft had the inside track on what to do next. She created her own low-budget press kits and sent them out to the various newspaper syndicates. The Detroit Free Press started running “Where I’m Coming From” in 1989. Eventually, more than 60 newspapers across the United States syndicated “Where I’m Coming From.”

One of the most distinctive things about “Where I’m Coming From” is that Brandon-Croft just draws the characters’ heads and arms. The reader does not see any other part of the characters’ bodies.

She decided to do that “mostly because in comics and other forms of media, you see women in terms of their bodies. You see cleavage to sell popcorn. You’ve got to have these legs or you’re going to have the tiny waist, you know, superwomen.”

And she didn’t want to do that.

“I just want these women to be talking. And I just wanted to be where they’re coming from, you know, what their point of view is,” Brandon-Croft explained.

“I was hoping to create an atmosphere of intimacy,” she continued. “You’re kind of eavesdropping, and you’re hearing what these ladies who are friends are talking about.”

“Where I’m Coming From” comic strips by Barbara Brandon-Croft. Photo courtesy of Barbara Brandon-Croft Brandon-Croft said a lot of her characters are facets of her.

“So somebody like Jackie, who’s very high-strung and emotional is just kind of me,” she said. “Also, Lakeisha, the one who has the stylized dreads, I use her when I want to make a strong statement. Then there’s somebody like Nicole who’s just this cute girl. Doesn’t care about much else, but being cute and herself … But she’s not one of my smarter characters.”

-

Jordan Harper's journey from 'The Mentalist' to suspenseful crime novels

The great mystery writer Dennis Lehane says that if James Ellroy and James M. Cain had a love child, it would be Jordan Harper. Which checks out, because Ellroy is one of Harper’s literary heroes.

Harper’s novel, “She Rides Shotgun,” won the 2018 Edgar Award for Best First Novel by an American author. And we wouldn’t be surprised if Harper wins another Edgar for this follow-up, “Everybody Knows.”

This compelling novel focuses on a publicist named Mae Pruett who works for one of Los Angeles’s most powerful crisis PR firms.

Harper writes so eloquently about the City of Angels that L.A. feels like one of the characters in the novel. But his vision of the city doesn’t include many angels. Before he started writing fiction, Harper worked in television as a writer for the CBS drama series “The Mentalist.“

“The Mentalist” was a drama series that aired on CBS from 2008 to 2015. The show focused on Patrick Jane, played by Simon Baker, who worked as a consultant for the California Bureau of Investigation, or the CBI. He used his supposed powers as a psychic medium to help CBI agents solve murders. Patrick Jane worked with law enforcement in order to track down the serial killer who had murdered his wife and daughter.

“I learned by helping produce over 140 episodes of the show, and writing 14 of them, a really strong sense of structure and storytelling that I would equate to like maybe if somebody learned how to do architectural drawings before becoming an artist,” Harper told Wisconsin Public Radio’s “BETA.” “It’s the most precise and mechanical form of storytelling you can do. And I think it’s a really strong base to start off with.”

Pivoting from writing for TV to writing novels

Harper wrote crime-based short stories before turning his attention to novels. One of his short stories was adapted into a script, which helped him get a job in television.

“I’ve always had fiction as a primary thing that I wanted to do,” he explained. “But as much as I loved writing for ‘The Mentalist,’ it was such a relief to get to write in a world where I didn’t have to worry about studio notes or network rules about what you can and can’t do and to write something that was just more purely what I wanted to do as a storyteller.”

Jacket design by Kirin Diemont Jacket photographs by Getty Images Jacket (C) 2023 Hachette Book Group, Inc. And this is the world he was in while writing “Everybody Knows.”

The protagonist in “Everybody Knows” is Pruett, a “black-bag” publicist.

“A ‘black-bag publicist’ is my term for a crisis manager,” Harper said. “The way I explain it in the book is she’s a publicist who doesn’t get the good news out. She keeps the bad news in.”

“And she is the person who is tasked with cleaning up the messes for the rich, powerful and famous. Anytime you read any kind of news about a powerful person who’s been accused of something terrible, you’re going to find a crisis manager in there somewhere. Whether or not their name gets mentioned in the story, they’re there,” he added.

Location, location, location

The opening chapter of “Everybody Knows” takes place at the famous Chateau Marmont Hotel in L.A., which is where John Belushi passed. Harper actually wrote this chapter in one of the hotel’s bungalows.

“I’m a big believer in vibes. I’m a big believer in getting the atmosphere right, not just the sights and sounds, but the feeling of something and trying to transmit that,” Harper explained.

He credits his appreciation for vibes to Megan Abbott.

“She paints a dream that is so vivid with her word choice in the way that she lives so deeply in the characters,” Harper said. “And you feel what they feel and you see not the concrete world that exists, but the world that they see. And you notice what they notice. And I just think it’s really beautiful.”

He said that he can’t of a think better way of doing that than going to a place he’s writing about, sitting there and living in it.

“I did check into the Chateau Marmont for a couple of days to start the book. But I also wrote in a lot of other places. The beauty of a laptop is you can get in your car and you can drive to Koreatown. You know, you can drive out to the beach and take a look. You can see what’s there. And a big part of this was trying to capture as much of Los Angeles in a book as I could.”

Episode Credits

- Doug Gordon Host

- Adam Friedrich Producer

- Steve Gotcher Producer

- Steve Gotcher Technical Director

- Kyle Edward Ball Guest

- Barbara Brandon-Croft Guest

- Jordan Harper Guest

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.