Henry Winkler talks about being the Fonz, his connection to Milwaukee and HBO’s ‘Barry.’ Also, actress Illeana Douglas on her love affair with Connecticut movies. And Mark Mothersbaugh on how DEVO predicted de-evolution fifty years ago.

Featured in this Show

-

Henry Winkler: The search for the you in you

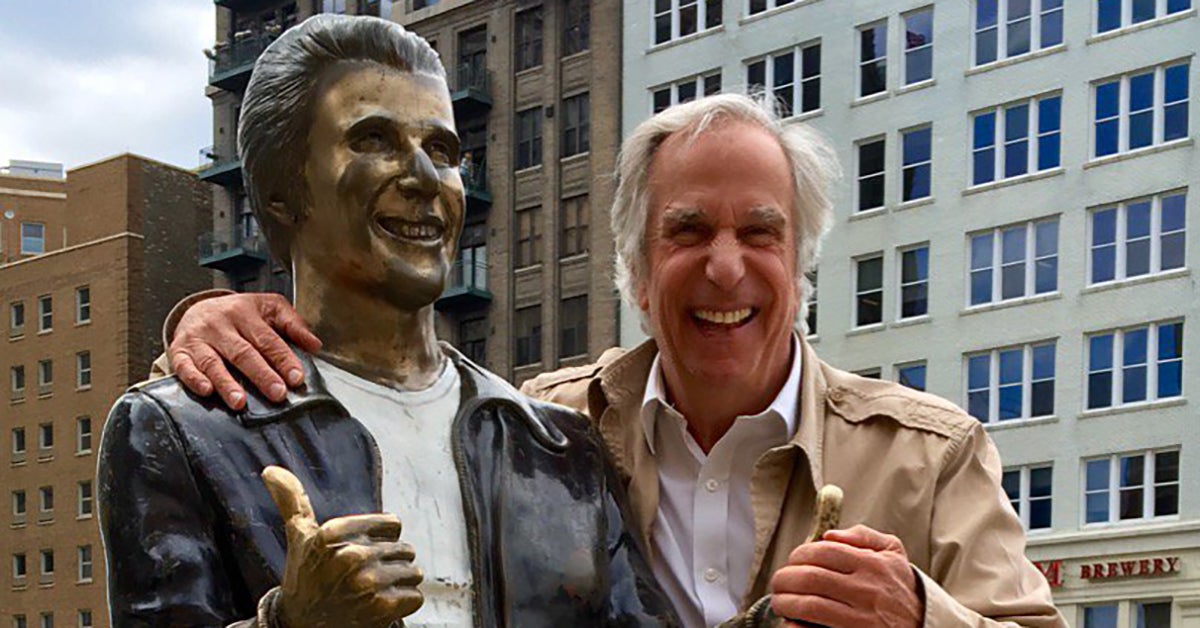

Wisconsin Public Radio’s “BETA” has never talked with anyone who has a bronze statue of their likeness displayed publicly. That is, until now. Standing 5 feet, 5 inches tall, the Bronze Fonz proudly resides on the River Walk in downtown Milwaukee.

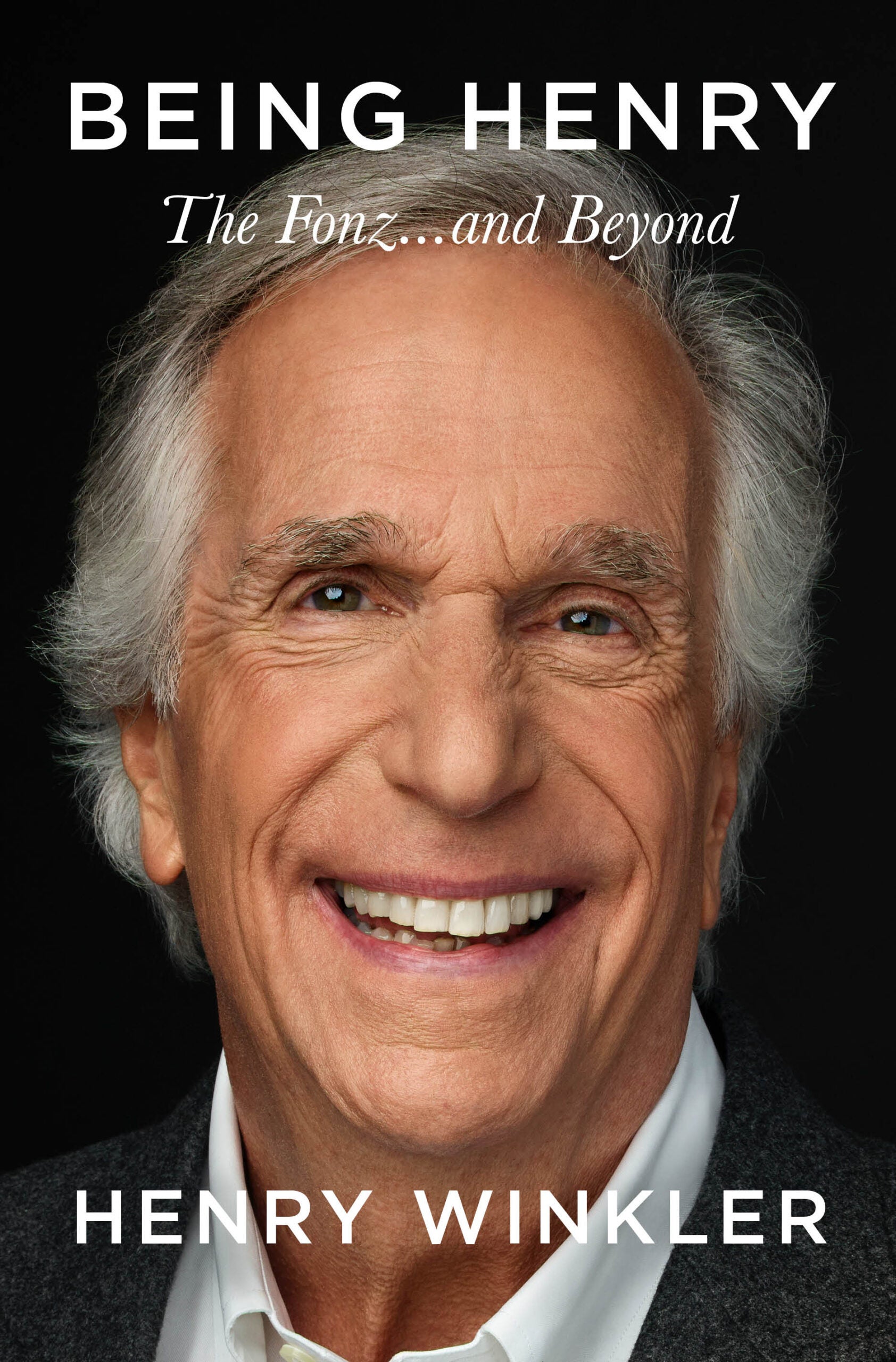

“BETA” talked with the actor who played the character of Fonzie on the 1970s television show “Happy Days,” Henry Winkler. He’s recently released a memoir titled, “Being Henry: The Fonz …and Beyond.”

He tells us that having a bronze statue of oneself can lead to touching encounters.

“I’ve been to Milwaukee many, many times as a public speaker or whatever the reason,” Winkler said. “I walk up and visit the statue, and there’s a couple taking selfies. And I said, ‘Excuse me, would you like me to take that picture? And they went, ‘Sure.’ And then they went, ‘Whoa.’ I’m taking a picture of them with a statue of me.”

To Winkler, the Bronze Fonz is a humbling example of how deeply the character of Fonzie has changed his life.

“How is it possible that someone who is told that he will never achieve, he will never meet his dream, that he will never be anything — all of a sudden, he is at the unveiling of a statue of a character he created in the character’s hometown?… It’s beyond words,” he said.

Book cover for Henry Winkler’s memoir, “Being Henry: The Fonz …and Beyond.” Photo courtesy Henry Winkler Much of Winkler’s low self-esteem as a youth is related to a learning disorder that kept him from doing well in school. He didn’t find out he had the condition until he was 31 years old.

“I was severely dyslexic,” he said. “I’m in the bottom 3 percent academically in the country. My parents had just come from Europe, and their education was everything. But education was a mountain I could not climb.”

“They were dismayed, embarrassed, cruel and punitive about my grades. I think that dyslexia also has an emotional component because I could not figure out life or school. I felt like I was nowhere,” Winkler continued.

Winkler turned his dyslexia into an advantage by overcoming its limitations. He said because of the condition, he found it necessary to improvise during his audition for “Happy Days.”

“I went off script, because I’m so dyslexic that I cannot read, and do something else off the page. So, you memorize as quickly as you can. And I don’t know why, but I changed my voice and immediately started talking to everybody in the room. And I was off,” he recalled.

“Then we finished. I had six lines. I threw the script up in the air and sauntered out of the room. Two weeks later, on my birthday, they called and asked if I wanted to be in the show,” Winkler said. “I said, ‘If you let me show the other side of this guy, the emotional side.’ They said yes. I said yes. And here I am sitting with you.”

Winkler’s dyslexia also created an opportunity for him to become the co-author, with Lynn Oliver, of a series of children’s books called “Hank Zipzer: The World’s Greatest Underachiever.” These books hold a special place in Winkler’s heart.

“They are the story of my life as a dyslexic. When I write them with Lynn, I clearly remember what it was like to be 8 and a failure — trying so hard and unable to do anything. Hank has great friends who do not treat him in any way terribly. They love him,” Winkler said. “They do not have dyslexia, and they understand him. Kids all over the world have asked me, ‘How do you know me so well?’ It is one of the great compliments of my whole life.”

In recent years, Winkler has played the role of the infamous acting teacher, Gene Cousineau, on (HBO) Max’s hit series “Barry.” We wanted to know if playing Gene had a role in changing his life.

“In so many ways. No. 1, it was a gift. No. 2, I don’t know that I could have played Gene Cousineau seven years earlier,” Winkler said. “I started therapy because I started getting lost. The first question I was asked was, ‘Where is the you in all of your story and the pursuit of the you?’ It allowed me to expand.”

“The more you know about yourself, the more you know about all things. The more you know about all things, the richer your character becomes in every aspect of anybody’s life,” he said. “I will tell you that the comment, ‘Oh my God, you are so incredibly beautifully complicated as Gene. I didn’t know Gene was within you,’ is giving me a vista.”

-

From 'The Swimmer' to 'The Stepford Wives': Illeana Douglas explores Connecticut cinema

There’s a specific line in the 1968 film “The Swimmer” based off the John Cheever short story that really resonates with actor, writer and film historian Illeana Douglas. It’s when Rose Gregorio’s character Sylvia Finney notes that her upper crust neighbor, Mrs. Merrill, won’t just eat plain mustard.

“Plain mustard ain’t good enough for Mrs. Merrill. She had to have Dijon mustard,” her character said.

For Douglas, that scene satirized and summarized so much about life in her native state of Connecticut.

“It’s just such a great Connecticut line,” Douglas told Wisconsin Public Radio’s “BETA.”

“I remember being in class-conscious Connecticut growing up, and if you were in someone’s house and they had Grey Poupon, it’s like you knew what that meant,” she said.

“(‘The Swimmer’) is about something that you have to accept in a place like Connecticut. It’s about these misplaced values — money, status, living in the right zip code and what happens when you’re stripped of all of that and you’re shunned,” she continued.

Douglas is the famed actor of “Goodfellas,” “Ghost World,” “Cape Fear” and “Stir of Echoes.” She’s also a noted film historian and author.

It was during the doldrums of her COVID-19 isolation in Los Angeles when she revisited “The Swimmer.” She was homesick but wasn’t allowed to travel. So she decided to visit emotionally through the film. When she finished, her curiosity was piqued as to what other films were set, filmed or otherwise tethered to Connecticut.

When she began to dig deeper, she found nearly 100 films that present the Constitution State to audiences from the silver screen and decided to flesh out her project into a book, called “Connecticut in the Movies: From Dream Houses to Dark Suburbia.”

“I found through the writing of the book that people choose to live in Connecticut for a reason. It doesn’t seem accidental that Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward chose to live in Connecticut. You’re near New York, but you’re not in the city,” she said. “It’s just a great place to live. There’s just a great sense of freedom.”

As fate would have it, as she was writing the book, an old fixer upper in her childhood neighborhood came up for sale and Douglas moved back home.

“The final funny part of the story was that my realtor friend sent me a listing for a house that I knew very well, you know, played in when I was a child. And I said, ‘Ah it’s kind of an intriguing idea. I did say I wanted to fix up an old farmhouse.’ And the next thing I knew, I was Mrs. Blandings,” Douglas said.

If you don’t get that reference, it’s from the 1948 film, “Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House,” starring Cary Grant. It’s about a New York couple that heads to Connecticut to construct their titular dream house. It also happens to co-star Douglas’ grandfather, the screen legend, Melvyn Douglas.

“I knew him as my grandfather,” Douglas said. “He was lovable and I looked up to him very much and wanted to impress him and please him. He was such a movie star, his looks and his charm and everybody loved him. And so, I had that childhood idea of him. But as I write about him as a grown up, and the more I’ve gotten into movies, that’s when I realized what an incredible actor he was, how similar our careers have been in many ways.”

While “Mr. Blandings” painted Connecticut in a charming, old Hollywood way, other movies offer a darker version.

Similar to how “The Swimmer” attacked Connecticut’s crusty class structure and the consequences of buying into the American dream, Douglas points toward the 1975 horror film “The Stepford Wives” as a deconstruction of the state’s rosy image.

“The director Bryan Forbes, who is British, and the screenwriter William Goldman, they put sort of a spin on it that I think cast an impression of Connecticut, that Connecticut is Stepford,” she said.

“Ever since ‘The Stepford Wives,’ you have an impression that if a movie is placed in Connecticut, something very bad is going to happen. And that’s what ‘Stepford Wives’ succeeded in doing.”

Douglas reexamined the film and stated how the satire Forbes and Goldman thought they were projecting was wildly misinterpreted.

“This was the height of the women’s movement. And they had this scene where Katharine Ross is saying to her friend, ‘I’m no bra burner,’ which was a derisive term,” Douglas said. “Again, one of the great screenwriters of our time, William Goldman, somebody who’s always sort of lauded, and he’s putting these ideas out there and they’re just completely sexist.”

The book concludes on an essay that combines Douglas’ separate passions. It’s about the 2011 indie Connecticut film “The Green,” which she starred in. In a charming essay that includes home photos of her mom’s homecooked craft services meals for her co-stars, Douglas talked about her pride in working on that film.

“It was going to be the first gay film made in Connecticut and I was thrilled to be a part of it. I had always wanted to make a movie in Connecticut and have that experience,” she said.

The film, written by Paul Maracarelli (who you may know as the “Can you hear me now?” guy from old cell phone commercials) follows the saga of a teacher Michael, played by Jason Butler Harner, who returns home to teach and is accused of molesting a student.

“He has to defend himself and the town kind of turns against him, which is a theme in a lot of Connecticut films. And by the end, they realize that, he’s not guilty and they come back and embrace him. And he has a sort of a sigh of relief,” she said.

Douglas applauded Maracarelli’s boldness in telling the story. He’s from New Haven and was unsure how his interpretation would be received by residents filming in Connecticut.

“Doing a film like that where you’re saying some negative things about Connecticut, he wasn’t sure that they were going to embrace him and they did,” Douglas said. “So, yeah, it was a great film to be involved in. And again, one of the great things about the book is that people take a second look at ‘The Green’ and some of these other Connecticut films.”

“Connecticut in the Movies: From Dream Houses to Dark Suburbia” is available from Lyons Press.

-

Devo co-founder Mark Mothersbaugh on 50 years of de-evolution

If you watched “Saturday Night Live” on Oct. 14, 1978, you would remember the musical guest — the new wave band, Devo. Give guys in matching yellow hazmat suits herky-jerkying on stage like robots whose batteries are running out as they performed their deconstruction of the Rolling Stones’ hit, “I Can’t Get No Satisfaction.”

Unlike most bands, Devo has a fascinating philosophy. They believe in de-evolution — the idea that humanity is actually regressing instead of progressing. And unfortunately, they are absolutely right. The world is getting worse, just like Devo warned us.

The band is currently touring to celebrate its 50th anniversary.

Wisconsin Public Radio’s “BETA” spoke to Devo’s co-founder Mark Mothersbaugh backstage in Green Bay. Thanks to our friends at “To The Best of Our Knowledge” for allowing us to air this conversation, which originally aired in 2006.

On de-evolution philosophy

Jerry Casale and Mark Mothersbaugh met as students at Kent State in Ohio at the end of the 1960s. They were there when the Ohio National Guardsmen killed four students protesting the Vietnam War in May 1970. Casale was 15 feet away from one of the students who was killed. Mark Mothersbaugh says that the Kent State riots had a direct effect on Devo’s worldview of de-evolution. Devo’s philosophy is summed up best in their song, “Jocko Homo.”

“I had a pamphlet called ‘Mark Mothersbaugh Heavenbound.’ It talked about evolution being impossible. And Darwin went against all the tenets of religion. And so, we were able to appropriate a lot of information from people like the Jehovah’s Witnesses that would come around, and they would constantly rail against evolution.”

“We were just trying to come up with some sense to what was going on around us. We saw technology manifesting itself as nuclear reactor problems, people getting poisoned by pesticides and just all the chemicals that we were dumping into the atmosphere. It just seemed to us with everything that was happening, the economy in our hometown (Akron, Ohio), frankly, we just saw everything adding up to de-evolution, making more sense than evolution.”

“Somebody recently told me that they have video footage of us playing at a biker club where the bikers started tearing up the club when we were playing ‘Jocko Homo’ and they were going, ‘You calling us an ape?’ And they’re basically behaving like apes. Yeah, actually, living up to the song or down to it. But just being a lightning rod for hostility with people that were that wrong, I felt like we had to be doing something right. And so it was inspiring in a way.”

“That was 25, 30 years ago now. On stage tonight, Jerry (Casale) is going to go, ‘Who out there believes de-evolution is real? ‘And you’ll hear the whole crowd roar because now, people, they see it all around them. They see it everywhere from the White House on down to all the doublethink and all the parallels to ‘1984’ that exist in the world we live in.”

“Unfortunately. Our intention wasn’t to be correct. We would have liked to have been proven wrong.”

On ‘I Can’t Get No Satisfaction’

One of Devo’s greatest songs is actually a cover version (quite possibly the best cover version in the history of music). Mothersbaugh explains what led to the band’s robotic reinterpretation of the Rolling Stones hit, “I Can’t Get No Satisfaction.”

“We were rehearsing back in ’75 or ’76 in Ohio, and we had some friends who had a car wash. Of course, in the winter, it’s too cold to use a car wash. So this guy had a place where he stored the chemicals out behind it and he let us rehearse in this room. It was just a cinder block room with no heat. So we were all in there and it was below freezing. You know, there’s a lot of snow. We had to drive through the snowy car wash to get to this place, and we’re staying there. And, you know, we have gloves and coats on and we’re playing. And Bob Casale (Jerry’s brother) started playing that kind of like Persian goose-stepping guitar part that starts it off. And everybody just kind of started filling in parts with frozen limbs. And somehow the lyrics all of a sudden made more sense to me than they ever did. And then I just started singing those lyrics over top of it and it made everybody laugh.”

On ‘Whip It’

Devo’s biggest hit in the U.S. was their 1980 song “Whip It.”

“You know what I think it was? I think it’s just because of all our songs, it was the one that disc jockeys misconstrued as being about sex in some way,” Mothersbaugh speculates. “We’d be sitting in a radio station waiting to go and talk to the deejays in the next room, and they go, ‘Well, I got Devo here, and I got to say, I whipped it just this morning.’ And they’re all in there laughing. Nobody really knew it was actually about Jimmy Carter.”

“When we wrote it, we’d just come back from tours where people were b—-ing about Jimmy Carter all over the U.S. and even Europe. They were saying his foreign policy’s sucky. He’s always fluctuating in that he doesn’t take a strong stand on things, and he’s not a good leader. We wrote a song which is kind of like a Dale Carnegie, ‘you can do it’ kind of thing.”

“But on one level, that song was our dumbest song because everybody got into it as a disco song. People would say, ‘It’s such a great dance song.’ They’d all dance to it. And most of the people that we’re listening to ‘Whip It,’ they didn’t even know about ‘Jocko Homo’ or other things we were writing before that were even on the same album.”

On the band’s legacy

“I think our attempt was to permeate the culture on a number of levels, and that was a conscious goal on our part. And in that sense, ‘Whip It’ accomplished some of the things we were trying to do that we didn’t accomplish with other songs in the U.S.”

“We wanted to set ourselves apart from pop music, but yet at the same time kind of move into that territory. We wanted to occupy that territory, but yet give people something new to think about and something new to listen to. And we purposely chose uniforms that were not the uniform of the day.”

“Even now, I still meet people that go, ‘Yeah, I got my ass kicked because of you guys when I was in high school.’ And I hear that so much, it became a pejorative term even — Devo. Whether we had anything to do with it or not. They’d say, ‘You’re a Devo’ to the person that was slightly different at school, and then they’d get their ass kicked by the jocks and the in crowd. And so we did become kind of what we wanted to be, which was like a thinking man’s Kiss. At our best.”

“We were just saying, ‘Use your brain. You’re capable of so much more than just mindlessly buying the rap and letting someone else tell you how to live your life. Question everybody, especially authority, and choose your mutations carefully.”

Episode Credits

- Doug Gordon Host

- Adam Friedrich Producer

- Steve Gotcher Producer

- Doug Gordon Producer

- Steve Gotcher Technical Director

- Henry Winkler Guest

- Illeana Douglas Guest

- Mark Mothersbaugh Guest

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.