For generations, through wars, crisis and political upheaval, documentary poets have helped make sense of some of our most difficult moments by expressing what might otherwise be impossible to say.

Also known by some artists as “poetry of witness,” the genre employs verse driven by interviews, use of archival documents, newspaper reports, facts and statistics. While the documentary style might be more familiar in film, poets like William Carlos Williams, C.D. Wright and Muriel Rukeyser are known for their work in this area. Considered the “godmother” of documentary poetry, Rukeyser wrote “The Book of the Dead,” in the 1930s, a long investigative poem about a mining disaster in West Virginia.

While this poetry, sometimes called “docupoetry,” is a lens throughout history, it’s very much a current style as writers grapple with covering climate change, elections and poverty.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

For a full episode focused on documentary poetry, “To The Best Of Our Knowledge” talked with writers today about their work in the documentary genre.

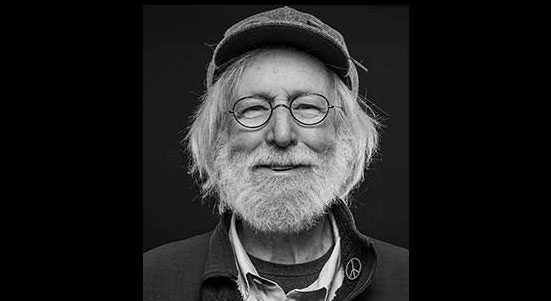

Philip Metres and Suncere Ali Shakur

Philip Metres, an Arab-American poet and professor in the Cleveland area, met activist Suncere Ali Shakur on a bench outside a public housing apartment in Cleveland where Shakur lives. Metres interviewed Shakur about his life. That interview became a poem for “To The Best Of Our Knowledge.”

“I think one of the jobs as a poet is to be a medium for other voices — particular voices that are often erased by power structures and racism and other structures of violence,” Metres said. “So my job at that moment was to try as best as I could to just be the antenna of that place and (Shakur’s) voice and that struggle.”

Shakur was hesitant at first.

“I was a little worried because I (wondered), how are you going to be able to get the essence of what I have to say if you haven’t been experiencing the things I’ve been through?” said Shakur, reflecting on what it was like to be interviewed for the poem. “But I went through it anyway. And to my surprise, I met a pretty good human being.”

Conventional tools of journalism, if misapplied, can be extractive — missing the humanity of the person at the center of the story, Metres said.

“What can a poem do, really, is to capture some kind of essence of a spirit in motion in the world,” Metres said, “with all of its longing and all of its past and all of its hope.”

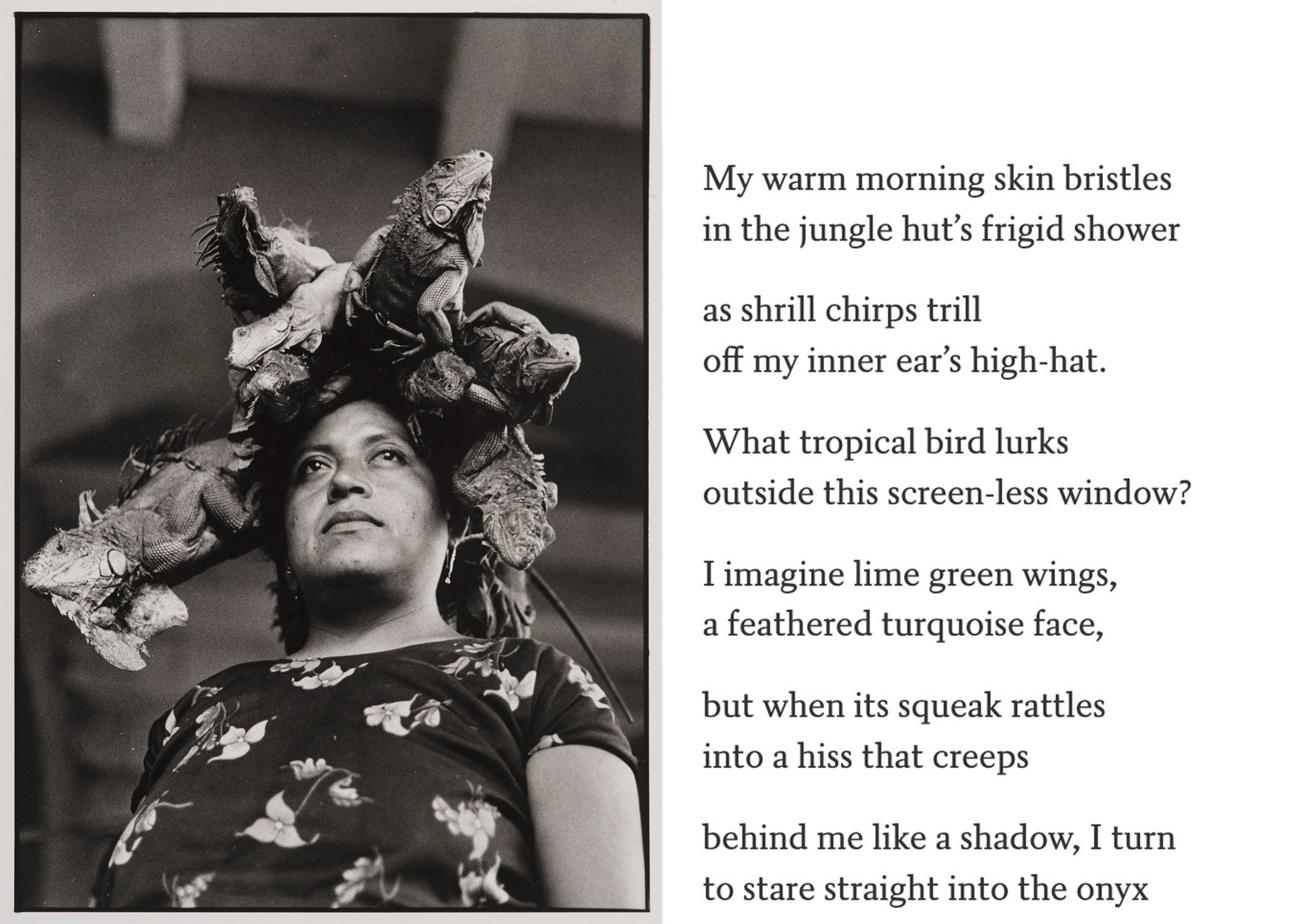

Kaia Sand and Portland’s Old Town

Poet Kaia Sand, who runs the newspaper Street Roots in Portland, Oregon, often writes poems that reflect her work with the unhoused population throughout the Portland metro. Her poem for “To The Best Of Our Knowledge,” entitled “This is how I drew you,” is a collage of what she sees on her many walks through the Old Town neighborhood there.

“That’s the place where the most people who experience homelessness here live, the most folks who experience homelessness die,” she said.

“I’ve always been really interested in how can we try to get at the same content using different forms or even different materials” Sand said. “I write a column every week. I hold news conferences about the number of people who died on the street…I don’t pick one vehicle.”

Poetry is uniquely and personally impactful though, she said.

“I’ll admit, this is the deepest for me,” said Sand. “When everything else falls away, I’m still pretty much a poet.”

Camille Dungy and everyday life

Poet Camille Dungy, whose most recent book is “Soil: The Story of A Black Mother’s Garden,” told Anne Strainchamps that the documentary aspect of poetry can be applied not just to the big news of the day, but also the daily mundanities that we report over dinner to loved ones.

“Because poetry invites readers to experience things emotionally, physically, in these other ways that aren’t just purely rational. They open space in our thinking about what we are witnessing in the world,” Dungy said.

In particular, Dungy said her family’s daily experiences of living through a global pandemic were well-captured in poetic verse, if only because those moments were both powerful and fleeting.

“What works in the best docupoetry is it makes a lived experience resonate longer and farther, like the difference between somebody just throwing a rock into the water and somebody’s who’s a really good stone skipper,” she said.

“Docupoetry” was produced for “To The Best Of Our Knowledge” in partnership with the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.