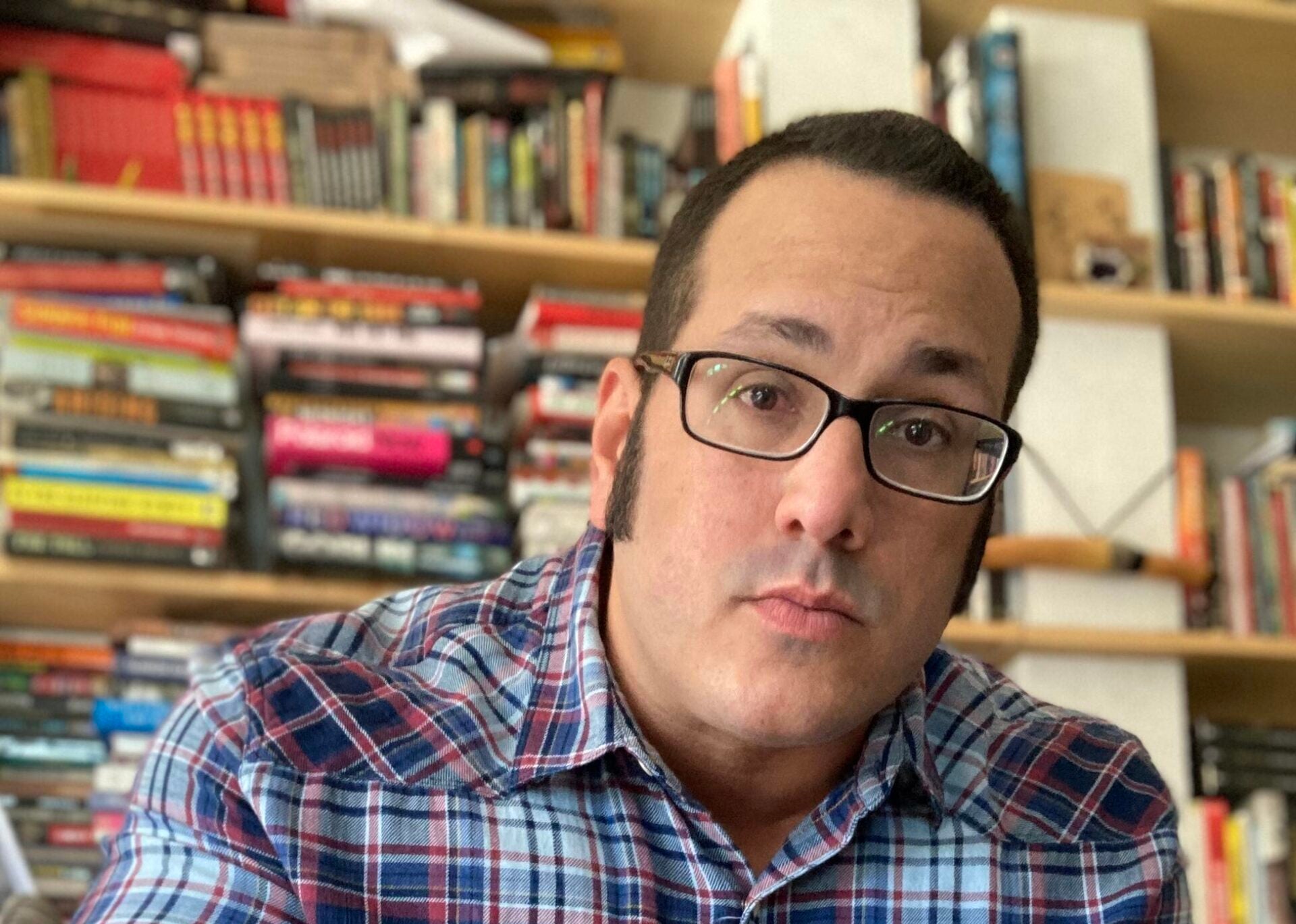

Pakistani novelist Mohsin Hamid has a knack for turning hot button topics into fiction. In his 2007 novel “The Reluctant Fundamentalist,” he waded into the debate over Islamic extremism. In “How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia,” he wrote about the problems of globalization in the form of a parody of a self-help book. His latest, “Exit West,” examines another major crisis: the refugees forced out of their homelands who are now migrants scattered around the world. The novel was a finalist for the Man Booker Prize and is now a bestseller.

Hamid told “To The Best Of Our Knowledge’s” Steve Paulson that the unnamed country in “Exit West” is modeled on Pakistan. It’s a love story in a city ripped apart by civil war.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Steve Paulson: Your novels typically deal with very loaded subjects. This one revolves around the refugee crisis and the explosion of migrants around the world. Why did you want to take on this topic?

Mohsin Hamid: I’ve been migrating my whole life, geographically. I came to California from Pakistan when I was three, went back to Pakistan when I was nine, came to America at 18, London at 30, back to Pakistan at 38. So the growing anti-immigrant rhetoric that you’re seeing all over the world is something I take personally.

I wanted to write a novel that began to explore the idea that not only are migrants not villains, but that actually everyone is a migrant. It’s a universal part of the human condition to migrate.

SP: Why is everyone a migrant? The refugees I understand, but what about the rest of us?

MH: I think what happens in our lives is that we migrate through time. In a sense, we’re each a refugee from our own childhood — the school we went to, the people we played with, those things all changed. Some dispersed, some people passed away, and we can’t return to that time. We feel a sense of loss, and we feel that things change and continue to change throughout our lives. We often try to deny the sorrow and loss that occurs by migrating in time.

But I think that’s a mistake. It’s better to acknowledge that feeling and to see how it unites us with people who migrate across geographies.

SP: What I find so interesting about your personal history is that you moved back to Pakistan after living in both America and London. As you say, you’ve been a migrant yourself.

MH: Yeah. My wife is also from Lahore. Shortly after the birth of our first child, we started wondering whether … if we didn’t go back now, maybe we’d never go back. And we thought we’d go and see, did we still like it? Would we be happy there? And that was eight years ago. I can’t say living in Pakistan has always been easy, and sometimes I feel almost foreign in Pakistan, in the same way that I feel almost foreign in America or Britain.

SP: Almost foreign in what regard?

MH: I’m such a mongrel now — such a mix of things — that I never feel entirely at home anywhere.

But one thing I’ve found as I get older is that this sense of being a bit different — a bit foreign — allows me to connect with other people, because I’ve come to understand that almost everybody feels a little bit out of place for different reasons. The only daughter in a family with five sons, or the only gay child in a family where everybody else is straight. People can feel foreign for so many different reasons.

SP: I get the sense from your novel that you see the current situation with refugees and migrants as being a global crisis that we have barely begun to grasp.

MH: Yes, I think that the direction of human history is the direction of greater equality. Many of us believe that regardless of your race, you should be treated equally. Regardless of your gender, regardless of your sexual orientation, or your religious beliefs, or lack of religious beliefs, you should be treated equally.

The idea that somebody born in Milwaukee and somebody born in Mogadishu — that two children should have fundamentally different rights about how they can live and where they can live, and the child from Mogadishu should stay there in the face of violence and potentially die just because of the lottery of where they were born — that position is going to become more and more untenable. And in 200 or 300 years, people are going to look back at us — the people of today who denied refugees access and denied migrants access — and think that we are as barbaric as we think that slaveholders were for their treatment of black slaves as subhuman.

SP: Are you saying we need to get rid of national borders and people should be able to live wherever they want?

MH: Look, national borders are pretty new. Until 100 years ago, there weren’t any passports. It’s not like the nation state with existing borders and immigration checks has been there since the beginning of time. People used to move around. It’s a new thing.

I think the real model shouldn’t be our countries. It should be our cities. You can move to New York from somewhere else and become a New Yorker. Cities grant their “citizenship” so easily. If you’ll abide by the rules and work hard, you can belong to a city.

Just so you know, the vast majority of migration in the world today isn’t from poor countries or rich countries — it’s from the countryside of poor countries to the cities of poor countries, like Lahore, which had 3 million people when I was born and 11 million people today. And Lahore is managing. I think that countries can too.

SP: We’ve been talking about a lot of political issues, but you are best known as a fiction writer. What can a novelist do to help us think about these issues?

MH: There’s a reason why we have storytelling – it liberates us from the tyranny of what has come before and what is now. It allows us to imagine what could be, which is incredibly important. And storytelling also allows us to cross the borders of our own self.

When you read a book, you’re sitting by yourself all alone. And in the same place of your thoughts, there are the thoughts of somebody else — the writer — coming in the form of this book. So in that moment you are you, but yet you have somebody else’s thoughts inside you. I think that’s an incredibly fertile and beautiful and productive and interesting space for human beings to occupy. Fiction has the power to make us transcend ourselves, question ourselves, connect with other selves in unique ways.

SP: It sounds like you’re talking about the capacity to create empathy, to give us a window into other people who were not like us.

MH: Absolutely. I think fiction does have the capacity to create empathy, but I think fiction also has a capacity to blur our own sense of self.

When we read about being a woman if we are a man, or being from a different country if we are from this one, it’s not only that we feel a sense of empathy for that other person — our own sense of who we are begins to blur. We occupy this fictional world for a while, dress ourselves up and play make-believe in our imaginations in a different world. And when you play make-believe, you are changed when you come back into “reality.” After reading the book, you’re not the same person who went in. So yes, there is empathy, but also there’s a kind of personal transformation that fiction does to each of us because we imagine different things.