Distinguished critic and journalist Vivian Gornick once penned a famous New Yorker piece titled “On the Street” where she wrote, “On the street nobody watches; everyone performs.”

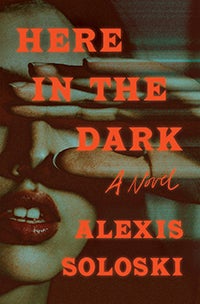

This philosophy of our innate human instinct and desire to perform underlies the rich subtext of Alexis Soloski’s superb thriller, “Here In The Dark.” It’s about a New York City theater critic who becomes entangled in a missing persons case that may or may not connect to the world of theater she covers.

The critic, also (perhaps serendipitously) named Vivian, was an actress in her youth and decides to return to performing to help unravel the mystery. But returning to her past threatens to reopen much darker secrets than her background as a thespian.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Soloski tells WPR’s “BETA” she was fascinated and inspired by Gornick’s view that we’re all generally in some state of performance. Soloski believes we all perform in daily social situations; that conceit interested her as a backdrop for a thriller.

“I don’t think that there is necessarily an opposition between performance and authenticity. But I do believe that a lot of behavior is learned performance. I know that I behave differently when I am with my children than when I am with my colleagues at work,” she said. “Sometimes it can be upsetting. I remember as a child being very upset when I would see my mother behave differently with someone else in the room than with me. And that felt very strange to me. But as an adult myself, I consider it fairly normative.”

Soloski also cites the great critic George Bernard Shaw in her epigraph to “Here in The Dark.” Her protagonist, Vivian, is clearly inspired by Shaw’s approach.

“Shaw had this idea of the critical instinct, which is this thing in you, which is if you are a critic and you know that something is bad, it will destroy your soul to say anything different,” Soloski said.

Vivian is an acerbic, discerning and frank theater critic for a Village Voice-esque online publication. She has a lifelong affinity for the theatrical arts and revels religiously in the dark of the theater.

Until one day, when an unexpected call comes from a nascent reporter, David Adler, asking to interview her for a profile he’s doing on female critics. The conversation takes a bizarre and dark turn when David surfaces an old critique of Vivian’s acting.

“David wants to interview her, ostensibly about being a critic, and Vivian has plenty to say about being a critic. She has a decade of work under her belt,” Soloski explained. “But David seems to have other motives as well. He seems to want to know more about who she is personally, and he seems to want to know about her past, and that is not something that she discusses. She keeps her personal life and her professional life in entirely separate spheres.”

Stymied, Vivian politely but abruptly ends the interview. A few weeks later, Vivian is contacted by David’s fiancé informing her that he’s missing and she was the last person to see him.

Turns out, life is stranger than fiction. Soloski, a New York Times culture reporter and theater critic at the Village Voice, based the plot on a real-life story.

“It’s probably the most interesting thing that has ever happened to me. When I was in my 20s and working at the Village Voice, a man called the Village Voice and asked to interview me. He said he was a journalist, and he was writing a piece on how people got to be critics. I was young and female and a theater critic, which was kind of a rarity at the time,” Soloski said.

“I did the interview, and then I received a phone call a few weeks later saying that he had disappeared, and I was apparently the last person to have seen him. And this was upsetting, but it was also kind of exciting,” she continued. “I ended up talking to a private investigator that the family had hired, and at a certain point I just left it alone. It always stuck with me because it was such a strange thing. And so, I’ve always wondered, well, what would have happened if I’d pursued it?”

I mean, what’s fiction if not a kind of performance on the page?

Alexis Soloski

Soloski understood a setup this juicy was a prime scaffolding for a thrilling novel.

“There’s nothing like having a plot handed to you. Like that’s not a gift horse I want to look in the mouth too much,” she quipped.

Using her extensive theater background in both criticism and improv, Soloski pulls back the curtain, literally, offering readers an insider’s perspective of Broadway and the transactional NYC theater world in general.

“There’s a long, long, long, long history going back all the way to Plato, if you want to get fancy about it, of what we call the anti-theatrical prejudice,” Soloski said. “That’s people just really not liking theater, thinking the theater is fake, theater is false, theater is put on, theater is make-believe.”

“I’m not saying they’re 100 percent wrong. Theater is make-believe,” she continued. “But I choose to think that that is wonderful and additive rather than bad, and something that we should avoid. I think it’s wonderful to create. I think it’s wonderful to perform. I think it’s wonderful to make things up. I mean, what’s fiction if not a kind of performance on the page?”

The deeper Vivian gets into the case of David’s whereabouts — aided by her narcissistic friend, an unreliable detective and too many pills and drinks — the greater her own personal descent.

She gets into character to see if she can infiltrate a suspicious online betting website that David worked at. That simple act threatens to reopen past trauma for Vivian. Here again is a case of art somewhat imitating life. Soloski was an actress and performed improv.

“Vivian, my protagonist, quits acting, out of a great trauma. I just quit acting because I wasn’t very good at it,” she said. “I thought maybe it would be nice not to have an eating disorder. So, there was no trauma. There was no great break up. I decided that I was much better off as a journalist.”

You can’t make good out of a void.

Alexis Soloski

Turns out though, Soloski’s background in improv and the “Yes, and” philosophy of improv helped structure the novel’s energy, flow and pace.

“I am good at some things. I’m smart. I’m quick. I do well in certain kinds of comedy. I have an ear for pacing,” she said.

“There is something about committing to a novel where you just have to go with your instincts and you just have to go with your choices. And you do have to turn your own critic off,” Soloski continued. “I certainly have moments when I’m writing where I think to myself, ‘This is bad, this is bad. It is a humiliating thing to be writing something this bad.’

“But I also have the wisdom and the experience gleaned from years of journalism and wonderful and sympathetic editors to know that you can only make something good once you have something that exists on the page. You can’t make good out of a void.”

The novel twists and turns its way toward a satisfying ending, but it also explores the important yet fragile symbiotic relationship between critic and performance.

Well-versed in that balance, Soloski says it’s all about the sliding scale of how you apply Shaw’s philosophy about criticism.

“There are ways of saying this more and less kindly. That’s probably the sliding scale,” she says. “You cannot delude yourself — if you have the critical instinct —into believing that something is good if it’s not. I also believe, of course, the goodness is a deeply subjective form and that not everyone will agree. But if you, in the depths of your soul, feel that something is not good, you have no choice as a critic but to say that, so I do agree with that.”

- Doug Gordon Host

- Alexis Soloski Guest