Every summer, publishers flood the market with the latest crop of beach reads — summer page-turners in popsicle-colors, served up as book candy you can scarf down in an afternoon. But if you’ve got three hours of uninterrupted time in an Adirondack chair with a view, why would you waste it on something forgettable?

Think about it: long summer afternoons are made for big books, books with challenging prose that you have to read and re-read three times over. Stories with so many characters you need a spreadsheet to keep track of them. Books you’ve been meaning to read for ages but scared you away for one reason or another. Summer is the time to face your fear!

In that spirit, “To the Best of Our Knowledge” producers gathered a summer book list that is equal parts gripping and fearsome.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Of course there are the usual suspects for a quixotic literary journey — “Don Quixote” or “Ulysses” or “War and Peace”?

Great works, but we wanted to go deeper. For some big, weighty books that don’t make it off the bookshelf all that often, we asked a group of incredible contemporary writers what they would recommend you sink your teeth into.

The Full List:

- “Anna Karenina” by Leo Tolstoy

- “Conversations in the Cathedral” by Mario Vargas Llosa

- “Wide Sargasso Sea” by Jean Rhys

- “Dark Reflections” by Samuel R. Delany

- “Moby Dick” by Herman Melville

- “Labyrinths” by Jorge Luis Borges

- “The Sea, The Sea” by Iris Murdoch

- “Freshwater” by Akwaeke Emezi

- “Middlemarch” by George Eliot (Mary Anne Evans)

- “On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous” by Ocean Vuong

- “Annihilation,” “Authority,” and “Acceptance” by Jeff VanderMeer

- “Ashes To Ashes: The Songs Of David Bowie 1976-2016” by Chris O’Leary

- “The KLF: Chaos, Magic And The Band Who Burned A Million Pounds” by John Higgs

- “Love Medicine” by Louise Erdrich

- “Codex Seraphinianus” by Luigi Serafini

- “Snow” by Orhan Pamuk

“Anna Karenina” By Leo Tolstoy

Turkish writer and Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk loves “Anna Karenina” by Leo Tolstoy specifically because of how complicated it is.

This 800-plus-page novel has more than a dozen major characters and portrays the life of imperial Russian society. Though it is considered one of the greatest novels ever written, Pamuk said this is a novel about what is important in life — love, marriage, friendship, struggle, making money, community, family, history, and belonging. He said it is a miracle of a novel, filled with Tolstoy’s beautiful language.

And speaking of great lyrical novels try “Snow” by Pamuk.

Set in modern secular Turkey, it tells the story of a journalist investigating a spate of suicides in a small Turkish city where young girls are killing themselves because of the pressure from secular Turkey to not wear headscarves.

“Conversations In The Cathedral” By Mario Vargas Llosa

Diplomat and writer Emily Parker said “Conversations in the Cathedral” by Peruvian Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa does an excellent job portraying life under a dictatorship in this novel.

Even though this is a long, complicated, and difficult novel, she said, “He creates this atmosphere of what it feels like to live in a world where you don’t feel free.”

“Wide Sargasso Sea” By Jean Rhys

Novelist Margaret Atwood — best known for the eerily prescient dystopian novel “The Handmaid’s Tale” — recommends “Wide Sargasso Sea” by Jean Rhys.

The story is one of the very first novels in which a minor character from another well-known novel takes center stage — in this case, the mad wife from Charlotte Bronte’s “Jane Eyre.”

Like Atwood’s own work, Rhys uses her characters to explore the power dynamics of men and women set against a dystopian world.

“Dark Reflections” By Samuel R. Delany

“There are two types of writers: those who write for other writers, and those who write for readers,” said Junot Díaz, author of the novel “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.”

Díaz is in the latter camp, and holds up “Dark Reflections” by Samuel Delany as a shining example.

The novel is a beautifully written reflection on the life of a closeted gay poet living in New York City, starting with the protagonist as an old man and works backward toward his youth.

Díaz said the novel is structurally fascinating, through which Delany reveals the soul of his protagonist in heartbreaking detail.

“Moby Dick” By Herman Melville

Ricardo Pitts-Wiley is the director and writer of the theatrical production of “Moby Dick: Then and Now,” which re-imagines Herman Melville’s tale in a context relevant to its cast — inmates at Rhode Island’s state juvenile correctional facility.

In their telling, Ahab becomes Alba, a teenage girl obsessed with revenge for her brother, who was killed by the drug trade — a stand-in for the titular whale. Pitts-Wiley challenges us to reread this classic and see the metaphor in our own lives.

“Labyrinths” By Jorge Luis Borges

If you want an ornate puzzle box of a compilation, then consider taking up the short stories in Jorge Luis Borges’ “Labyrinths.”

The Argentine writer is a master of meta-fiction, whose strange and impossible and fantastic short stories gave him the reputation as the godfather of magic realism. Borges described his own characters as those who “do not seek for the truth or even for verisimilitude but rather for the astounding.”

When “To the Best of Our Knowledge” executive producer Steve Paulson was a young man, Borges confounded him. That’s why when Paulson was handed the assignment of interviewing Borges — but with less than 24 hours to prepare — the opportunity felt like more of a curse than a blessing.

Now, more than 30 years later, Paulson has come to terms with the work of Borges and wishes his present-day self had the same opportunity to ask Borges the questions Paulson should have asked all those years ago.

We’re not all famous authors and thinkers, but the “To the Best of Our Knowledge” teams also likes to take up a challenge when it comes to vacation reading. Here are the books we’re excited to push ourselves through this summer.

“The Sea, The Sea” By Iris Murdoch

Host Anne Strainchamps: July 15 is the 100th birthday of the late novelist and philosopher Iris Murdoch.

I read a lot of her work in college, but that was a long time ago; I was another reader then. I was too young to appreciate one of her masterpieces, “The Sea, The Sea,” which centers on an aging, famous actor who retires to an isolated house on England’s coast to write a memoir.

A series of unexpected events and visitors — some otherworldly — strip away his self-delusion and deflate his ego but leave him with, perhaps, something better.

Murdoch’s great themes, in her philosophy and her novels, are about the lies we tell ourselves and the moral struggle to arrive at a reality-based truth. Sounds like a novel for our times, doesn’t it?

“Freshwater” By Akwaeke Emezi

Executive producer Steve Paulson: “Freshwater” is the debut novel by Akwaeke Emezi, a Nigerian writer who has settled in the United States. Unlike any other novel I’ve read, this is a mix of Igbo cosmology and gender-bending sensibility.

The main character, Ada, is possessed by multiple personalities — “ogbanjes” in Igbo folklore. Some of these spirit selves are male, others, female, and they pull Ada in different and sometimes quite destructive directions. The chapters alternative in perspective; some are told by Ada and others by the ogbanjes who inhabit her. The effect is poetic and surreal.

Emezi, who identifies as transgender, has called this an autobiographical novel. Emezi has undergone radical surgery to opt out of the gender binary and has written a remarkable autobiographical essay about this transition.

“Middlemarch” By George Eliot (AKA Mary Ann Evans)

Producer Shannon Henry Kleiber: I was an English major in college and while there are some classics I’ve read multiple times, for some reason I’ve never read “Middlemarch,” which came out in 1872.

The author is George Eliot, which is the pen name for Mary Ann Evans.

Although she was known for her writing under her real name, she decided to publish this book under a pen name since at that time, novels written by women were what she considered frivolous, lighthearted romances. She wanted it to be taken more seriously. It’s considered one of the first historical novels.

One of my favorite writers, Virginia Woolf, called “Middlemarch” “one of the few English novels written for grown-up people.”

I have no idea what that means, but it’s intriguing, and I’m going to find out.

“On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous” By Ocean Vuong

Producer Angelo Bautista: Ocean Vuong’s first novel tells the story of Little Dog, a writer penning a letter to his illiterate mother whose education was cut short by the Vietnam War.

The book draws a lot from Vuong’s own life. Much like his acclaimed and award-winning debut book of poetry, “Night Sky With Exit Wounds,” this novel deals with tough subject matter: the violence of war and of family, mental illness, race, queerness, and the body.

I find myself reading it in short bursts, not just because the poetic prose can be difficult, but because it is at once devastating and beautiful.

“Annihilation,” “Authority,” And “Acceptance” By Jeff VanderMeer

Digital producer Mark Riechers: “Meditative psychedelic nature writing” is about as apt a description of Jeff VanderMeer’s prose as I can think of.

He co-mingles imagery of naturalistic wonder and existential dread into fiction compared to Henry David Thoreau and Franz Kafka. In his award-winning Southern Reach trilogy, VanderMeer imagines Area X, an area of a coastal region that has been isolated by an unknown force, transformed into “unspoiled wilderness” that appears normal at the surface, but is populated by a menagerie of mashups of human, animal and plant forms, combined into new and sometimes frightening creatures.

Over three novels, characters explore Area X and analyze how it has shaped things inside and outside the “shimmer” that separates the zone from the rest of the world.

On their own, “Annihilation,” “Authority,” and “Acceptance” were not exceptionally challenging to read. What I struggled with was a crisis of imagination.

Filmmaker Alex Garland (“Ex Machina,” “28 Days Later”) adapted VanderMeer’s trilogy into a film version of “Annihilation,” which he describes as a sort of reimagining of the entire Southern Reach universe double-baked in his own interpretation of the imagery VanderMeer paints.

I watched the film with about half of “Acceptance” left to read.

While Garland’s vision is stunning, it is also a definitive vision of Area X, one without the ambiguity that so enthralled me when I started the series. VanderMeer’s fiction deliberately wavers between grounded naturalistic reality and surreal, weird geometry that you have to read a second time to make sense of. A film adaptation simply can’t bear that sort of ambiguity.

I stalled out — I’m still always carrying the books around with me, hoping to get back into the groove, but it’s just hard to jump back into my imagined Area X after seeing it on screen.

Learn from my mistake and finish the book first. That way your reading won’t get bogged down in comparing competing visions of what the Lighthouse should look like.

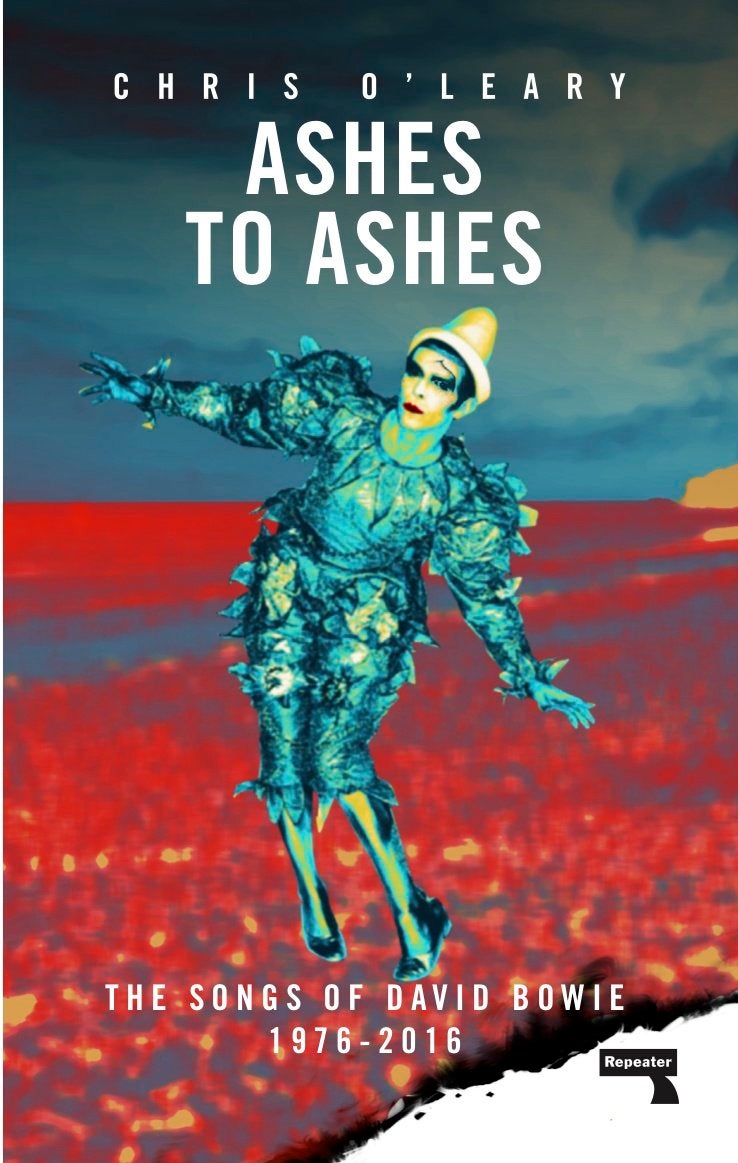

“Ashes To Ashes: The Songs Of David Bowie 1976-2016” By Chris O’Leary

Sound designer and technical director Joe Hardtke: It will be no surprise to my colleagues that I have music biographies on the mind this summer. And all the time. But right now, there are two I’m digging.

O’Leary’s “Ashes To Ashes” features expanded essays originally posted on his excellent songwriting blog, Pushing Ahead of the Dame, which chronologically explored the compositions of David Bowie. O’Leary contextualizes the period in which each song was crafted, then gets into the mechanics of building pop music: Chord progressions, arrangement, melodic inspiration.

On the surface, this would not seem like a difficult read at all. But things get interesting when he jumps into the mind of the composer.

Bowie prided himself on being well-read, often stealing ideas from remote corners of the literary world, and this is where the reader needs to do their homework. O’Leary draws from the 17th century plays of John Ford, pre-World War I Vorticist publications and the Cave of the Golden Calf. He ponders Jacobean era murder and amateur jazz scenes in 1960’s California. He makes musical parallels to 1990’s ambient music and free jazz saxophonist Albert Ayler.

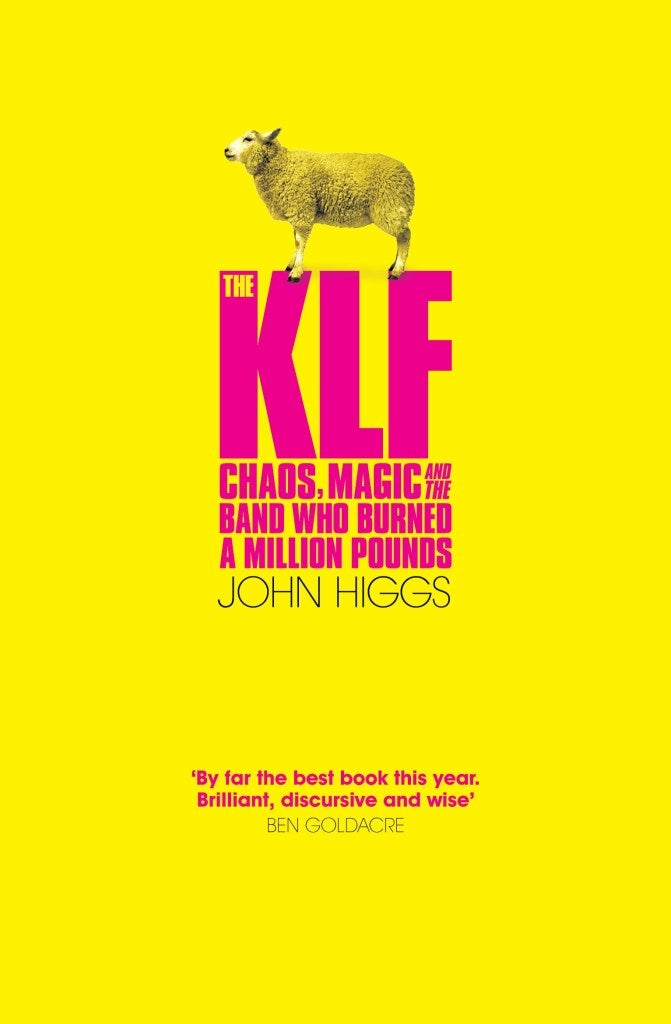

“The KLF: Chaos, Magic And The Band Who Burned A Million Pounds” By John Higgs

Hardtke: In “The KLF,” journalist and author John Higgs attempts to corral the thinking of a group that flaunted their own contradictions — pop anarchists of the 1990’s Jimmy Cauty and Bill Drummond. When they started sampling, they thumbed their noses at the success (and copyrights) of ABBA and Whitney Houston before releasing a string of world dominating songs in 1991.

After selling more singles than anyone else in the world that year, they retired, deleting their master tapes and controversially burning their last million pounds in a deserted Scottish boathouse.

Accordingly, Higgs is not afraid to confound the pop music reader with lengthy but fascinating asides on Discordianism, independent publishing on office copy machines, “The Illuminatus!“, underground theater, American conspiracy theories and Liverpudlian jangle-pop.

He somehow strings this all together to illustrate a magical pop period when witty, inexplicable spectacle was a legitimate means of expressing social concern. A period I deeply miss in our age of overwhelming earnestness and social media transparency.

“Love Medicine” By Louise Erdrich

Senior Producer Charles Monroe-Kane: A member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, Louise Erdrich explores Native American themes in her work, visiting and revisiting the North Dakota lands of her ancestors. She draws heavily on a native storytelling style set in a contemporary setting.

“Love Medicine” is her debut novel that spans 60 years of love triangles between members of the Ojibwa tribe living on the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation in North Dakota.

I have always been afraid of her work, “Love Medicine” in particular.

I’ve read the opening pages a few times, and each time, just as I’m drawn to the free spirit June Kashpaw — whom I strongly relate to — she freezes to death. She’s the main character and she dies on the first page, yet her ghost lingers, haunting and influencing the characters throughout the book.

Every time I start again, I think she will haunt me, too. I can see it coming now — sadness, guilt, and the only sweet being bitter.

“Codex Seraphinianus” By Luigi Serafini

CMK: This recommendation is difficult for a very different reason — it is literally hard to read. Hard to lift even.

Some background: Unprompted, an enormous tome — 14 inches by 20 inches and weighing more than 20 pounds — appeared in our offices, landing with a heavy thud on my desk.

It was magical. Full of bizarre illustrations and beautiful calligraphy in a made-up language. Everyone was talking about it — they wanted to touch it and “read” it, making vague attempts at parsing its meaning.

The lore surrounding the book is incredible to dig into. I spoke with the author Luigi Serafini and he told me he buried the only copy in a Vatican garden hoping it would be unearthed and inspire a cult. But he went on to say that his cat actually wrote it. So, there’s that.

The “Codex Seraphinianus” has spun off college courses, fierce linguistic debates, and even a few tattoo designs.

It would make one hell of a beach read — just be sure to lift with your knees.