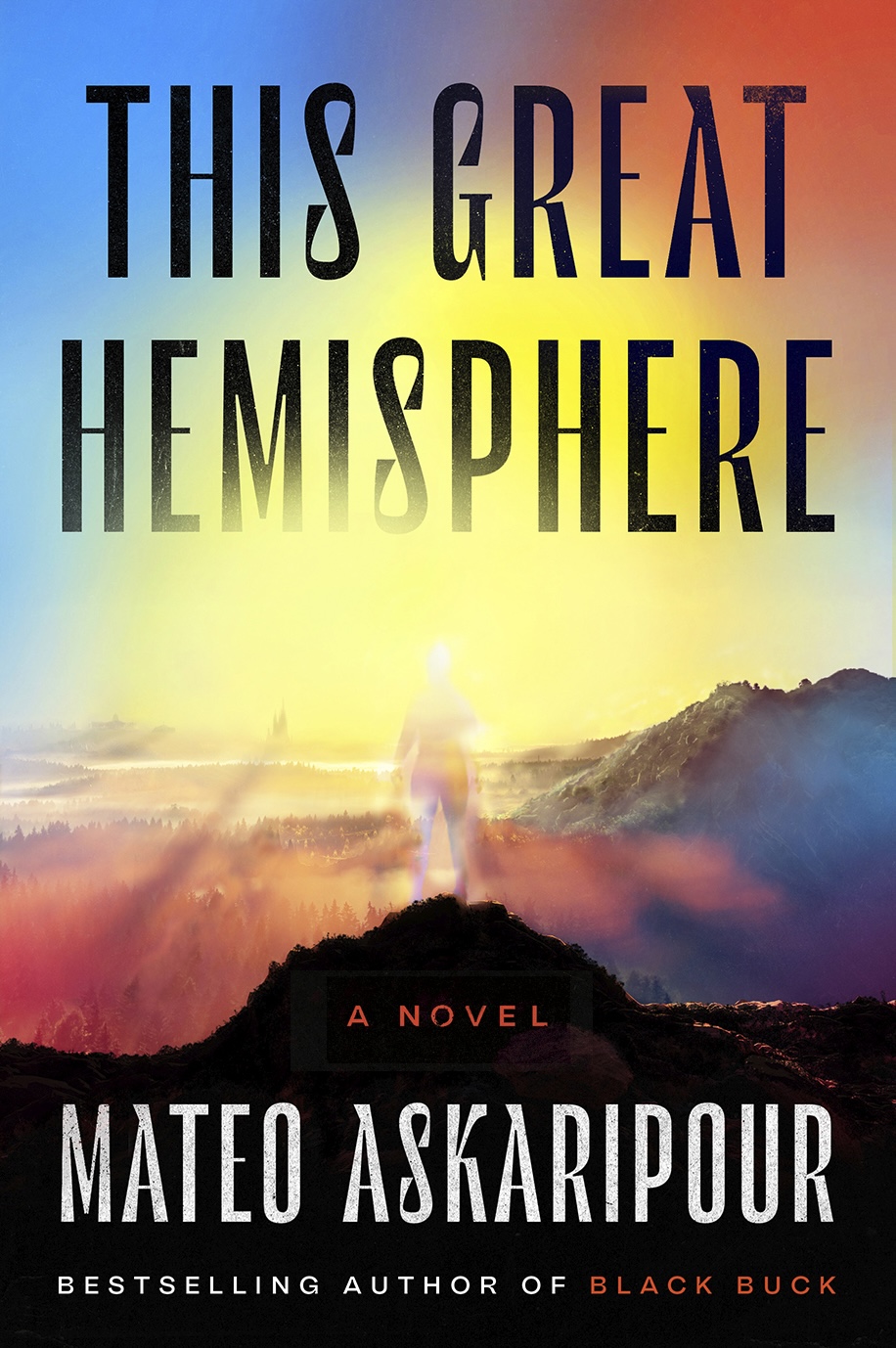

Mateo Askaripour’s startup satire, “Black Buck” was an instant New York Times bestseller when it was released in 2022.

And Askaripour is one of the most animated guests we’ve ever had on WPR’s “BETA.”

National Book Award winner Colson Whitehead said about “Black Buck”: “Askaripour closes the deal on the first page of this mesmerizing novel, executing a high wire act full of verve and dark, comic energy.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

So how did Askaripour follow up the success of his debut novel? Probably not the way you’d expect.

He wrote an incredible novel about power and ambition set 500 years in the future. It’s called “This Great Hemisphere.”

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Doug Gordon: Can you tell us about ‘”This Great Hemisphere” and why you decided to write it?

Mateo Askaripour: “This Great Hemisphere” I set 500 years in the future, in a world where there are invisible people who are literally see-through, and then members of the Dominant Population who have visible skin. It focuses on a young woman, Sweetmint.

Now, when the book opens up, Sweetmint’s brother, who she had lived with, who she loved, who was really the only person that she she could call family in her life or blood in her life, has disappeared. He’s been gone for three years.

She’s moving through that grief as much as she can, and she gains an apprenticeship with the premier inventor of the land, one of two men who had rebuilt the Northwestern Hemisphere from the ashes.

Now she’s working with this man. And then one day, she finds out the head of their Hemisphere has been murdered. And the primary suspect is her big brother, who she had presumed dead and was definitely missing.

Now there is a political upstart, a member of the Dominant Population, running on an invisible platform, who says, “I am going to become elected within five days and we need to find this guy.” Then there’s the top law enforcement officer in the land, also a member of the Dominant Population, who says, “No invisible is going to upstage me. I’m going to find this guy in five days.”

So it is a novel about many things: siblinghood, love, family, duty, ambition, power, as well as what does it mean to see and be seen?

DG: You wrote this novel from a fascinating point of view — close third-person POV. Can you tell us a bit about that, what that is and why you took this approach? I’d never encountered it before.

MA: So when I first drafted the novel, I was trying to write a short novel and I failed. And someone who had read an early version said, “This is an outline. Go rewrite this entire thing and go build the world.”

They also said two-thirds of this is written in close third-person. “Do you want to write in close third-person? If so, go streamline the entire novel.” And I said, “I don’t know what close third-person is. Maybe it’s due to a lack of having an MFA. I don’t know.”

But I had to Google close third-person. Close third-person is essentially third-person, but limited from the perspective of one person. So when I’m writing about Sweetmint, I am limiting the perceptions that I write about to her own.

I’m not going to have her in a scene with her and a surrogate father of sorts named Rusty, and share Rusty’s internal thoughts as well, or his perceptions of what’s going on. It’s limited the scope of Sweetmint in that way.

And this book uses a multi-POV, so three main characters or three main perspectives. There’s Sweetmint. There is Stephan Jolis, the political upstart. And then there’s Leon Curts, the top law enforcement officer aka Hemispheric Guard, the director of the Hemispheric Guards.

So when I’m in those chapters from their perspectives, it’s it’s written in third-person, but limited to their own points of view.

There are things in this book that are literally happening right now or have happened recently. And I’m not prescient. I am not clairvoyant.

Mateo Askaripour

DG: One of the biggest challenges you must have faced while writing “This Great Hemisphere” is all of the world-building you had to do. What was that like?

MA: The book continued to get more and more and more difficult until it didn’t. And in writing the world, at first I was overcompensating. I was writing every single little detail of every single place and every single person, and I was overcompensating because I was writing 500 years in the future.

And I at first, you know, foolishly thought that the more minute details I provided, the realer the world would be. But that’s just not how we exist, and that’s not how vibrant places come alive in a novel. They come alive through contrasts.

If I am pointing out every single little detail, then almost no detail matters and no detail stands out. So my incredible and incredibly gifted editor, Pilar Garcia- Brown, helped me see that and helped me pull out from draft to draft to further highlight the aspects of this world and the aspects of these people that I wanted the reader to see and I wanted the reader to feel.

So after the second or third draft, I stopped and I opened up a blank word document and I put “world-building” at the top, and I just allowed myself to ask every single question that came to mind. How long do these people live? How many people are in the Northwestern Hemisphere? How does a Northwestern Hemisphere compare to the Southeastern and the Southwestern and the Northeastern? What is the Northwestern Hemisphere’s form of government?

And then after I’d finished that doc and had about 7,000 words of world-building, I was better able to inhabit the world that I was building in and hopefully make it more habitable for readers.

DG: “This Great Hemisphere” is set 500 years in the future, but there are some things that resonate with our current society. Did that surprise you?

MA: No. There are people who have read and finished this book this week and they say, “Are you clairvoyant? What’s going on?”

There are things in this book that are literally happening right now or have happened recently. And I’m not prescient. I am not clairvoyant.

I am a student of history, and so much of what is happening today has already happened in different and similar ways throughout recent history. And we can assume throughout the millennia and millennia and millennia of humanity’s existence. So whatever is extremely relevant to today that is in the book, it’s just an echo of history.