A quick question for you: What do the following have in common?

Oddjob from the James Bond classic, “Goldfinger”; the legendary science-fiction author Philip K. Dick; Kim Jong Un; and the slasher movie, “Friday the 13th”?

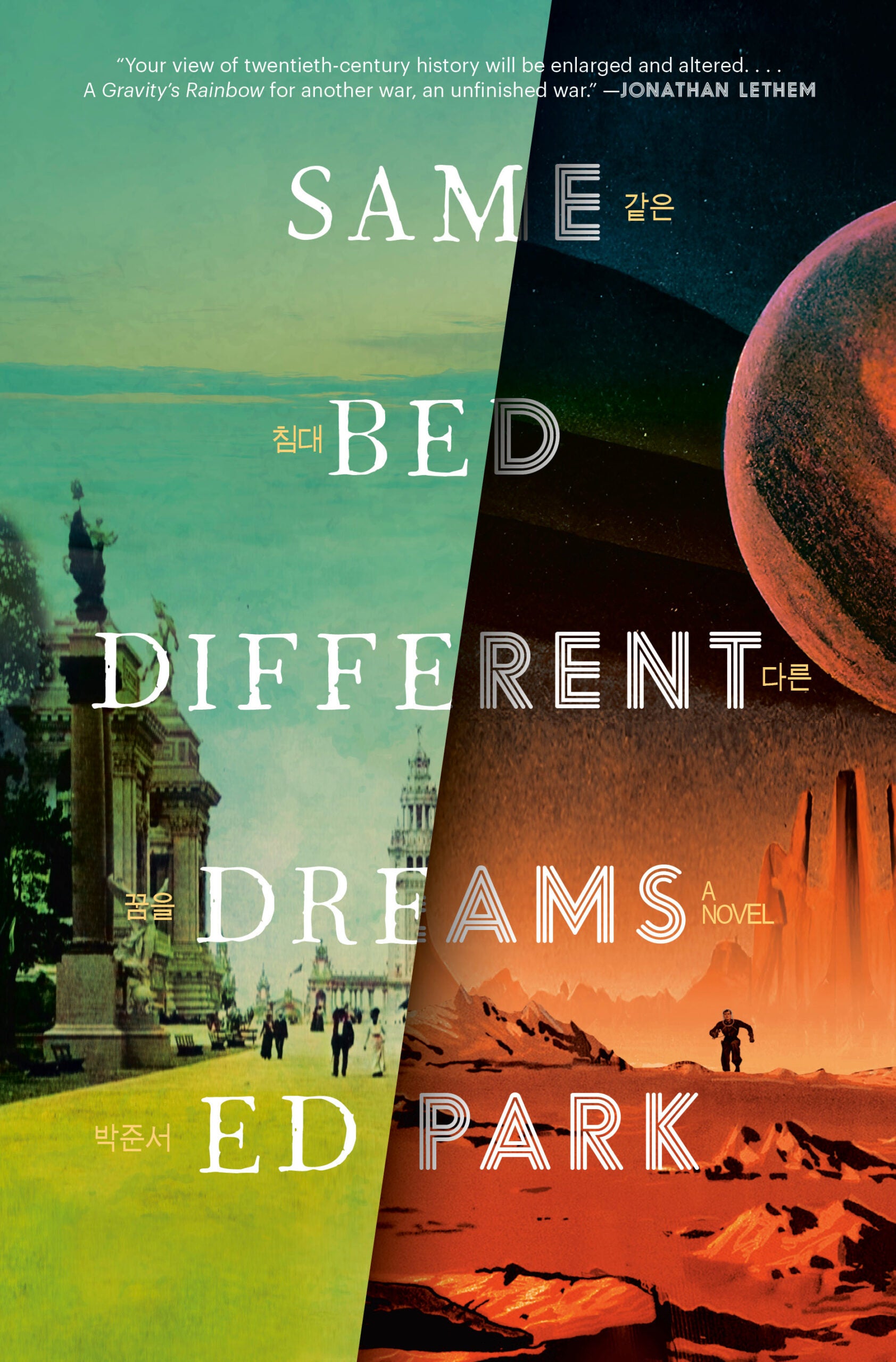

The answer is they all make appearances in Ed Park’s long-awaited second novel, “Same Bed Different Dreams.”

This book is unlike any other book I’ve ever read. And that is a good thing.

Park keeps the reader in a state of delightful disorientation. I had to go online to determine which characters were real and which owed their existence to Park’s incredible imagination.

Mind-bending questions started dancing in my head. Was there really a Korean Provisional Government? Are there really five kinds of different dreams?

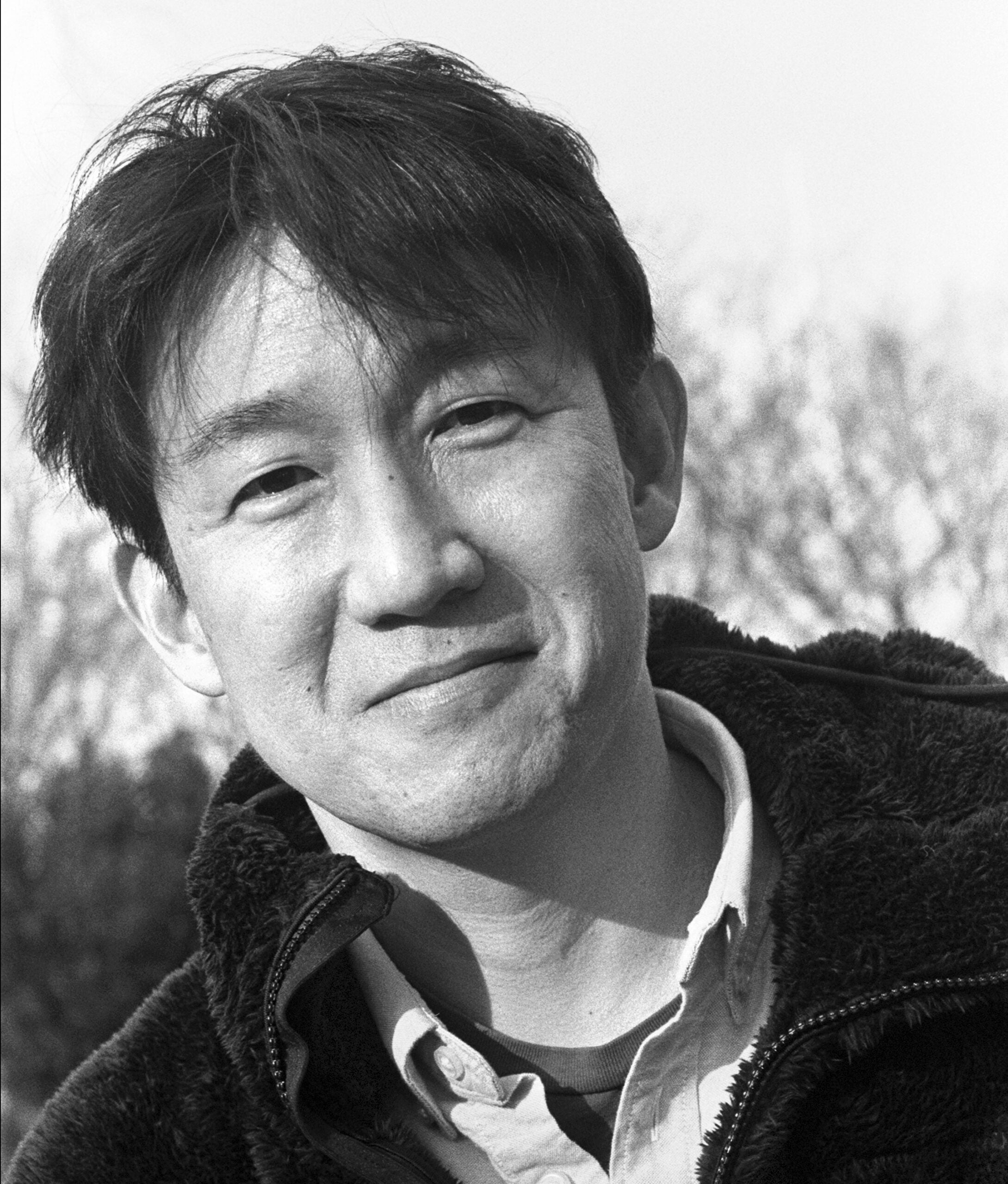

Park joined WPR’s “BETA” to answer these many questions.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Doug Gordon: What is the origin story behind “Same Bed Different Dreams”?

Ed Park: It’s an old adage in Asia, very popular in Korea, that my father wrote to me in an email once, probably, I believe, in the ’90s. I don’t even remember the context, but I just remember it being so evocative and poetic and just thinking that would be a great title for a book sometime.

It took another 10 years at least before I was working on something that I thought might justify that title.

On the one hand, what I started out with in terms of the writing was maybe a comedy of family, a comedy of relationships. “Same Bed Different Dreams,” meaning you don’t know what somebody else is thinking, even people very close to you — your family or friends.

DG: There’s a lot of humor in your work, and I really appreciated that. I’m guessing that one of the biggest challenges you faced would have been weaving the different storylines together. Was that indeed the case?

EP: It was until it wasn’t. During the writing process, I’m kind of going on one of the plot lines. It’s fairly linear, kind of the modern day. And then when I realized, oh, this character is going to be reading a book with this sort of outrageous alternative history of Korea, my mind is kind of like, wait a second, wait a second. I don’t know if this is the same book.

And then once it clicked, once I found a method of putting it in, something turns in my mind that I’ve been able to integrate it more. There are definitely, though, plenty of notebooks and kind of crazy-looking charts where I’m plotting who is connected to who.

There are fictional characters and then there are figures from history. There are elements from different movies and sitcoms and so forth. And to have them all connect in a satisfying way — there was a lot of brainpower and sweat involved in that.

DG: I can imagine there would be, but it was well worth it. I had to go online to figure out which characters were historical figures and which were not. So that was a good education for me. And you mentioned blending fiction and nonfiction, and that’s one of the great appeals of the book. But why did you decide to blend fiction and nonfiction?

EP: I think you can only tell certain parts of of history. And I guess I’m talking about modern Korean history and how it dovetails with American history. In order to do that, you need to talk about certain figures, right?

So one of the elements in the book is the very real group called the Korean Provisional Government, which is founded in 1919, kind of in protest to the Japanese occupation of Korea. They colonized Korea since 1910. And this is a real group that I read about years ago.

DG: The question “what is history?” is a recurring motif in your novel. Why?

EP: It’s a big question, obviously, and I think it was it was a question to myself. Why is it that these things that I’ve read or that have been told to me that I’ve watched, why have they stayed with me?

Why do I remember when Korean Airlines Flight 007 was shot down in 1983 by the Soviets? Why do I remember thinking how interesting that it was Flight 007 at the height of kind of my fascination with James Bond?

DG: As a Canadian, I’m pretty much legally mandated to ask you about the third overtime of Game Six of the 1999 Stanley Cup Finals between your hometown Buffalo Sabers and the Dallas Stars. Tell us what happened and why you decided to include this bit of hockey history.

EP: I was living in New York at the time. I’d been in New York for a long time, but I was born and raised in Buffalo for my sins. I followed the Buffalo Bills and the Buffalo Sabres and I played hockey growing up.

The Sabres have been to the finals twice. And I remember watching that triple overtime — Brett Hull’s skate is clearly in the crease. He scores. And even though later, I believe the NHL headquarters are like, “Yeah, his foot was in the crease, that should have been called.” It was too late. The cat was out of the bag.

And not long after that, I wrote a note to myself, just kind of playing around with certain obsessions. I thought that line about how the 1999 Stanley Cup finals was never finished.

Same with the Korean War, there was no actual peace treaty involved. And just like, what if somebody connected those two things? I threw that in there. And as you know from reading it, it kind of opened up this rich vein of Sabres lore. You know, trying to connect that to the larger movements of the book was was a lot of fun.

DG: And a lot of fun to read. How did the 1980 slasher film “Friday the 13th” find its way into “Same Bed Different Dreams”?

EP: I believe sometime in the 1990s, I had read somewhere Kim Jong Il — who was the son of the founder of North Korea, Kim II Sung, and the father of the current leader, Kim Jong Un, before he was elevated to the leader of North Korea upon his father’s death — he was a huge film buff.

He not only had a huge personal collection of movies, but he he wrote a lot about film production and how movies should be made. And I read somewhere that his favorite movie was “Friday the 13th.”

And I actually hadn’t watched it as a kid. I was a little bit afraid of slasher movies, to be honest, so I hadn’t seen that. But that question, I just thought, how interesting if true, right?

But when I finally came around to watch it, it was scary. It was violent, but there was something sort of intrinsic about it and almost like aesthetically, I was like trying to put myself in his mind.

Anyway, it was only upon reading this biography for the millionth time, I noticed a detail about his early life, that there was this moment where I was like, oh, I have a theory why this could have been his favorite movie. Like why he would have responded to it. So I felt kind of duty bound to include that in the novel itself.