In a new study, researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Madison found that children with an incarcerated parent whose family used resources from the education nonprofit behind “Sesame Street” experienced more positive social-emotional development.

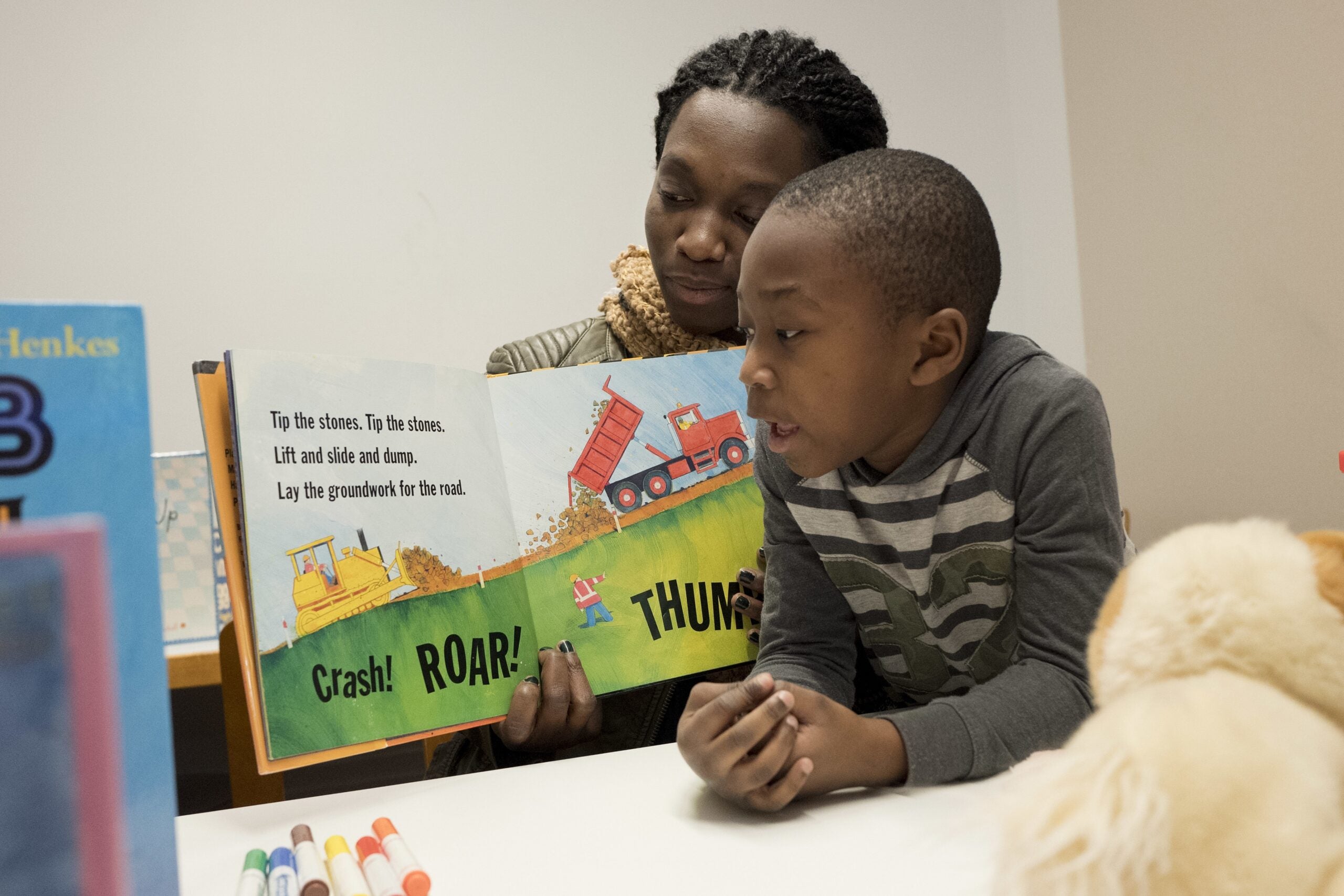

Sesame Workshop, which produces the PBS and HBO Max show “Sesame Street,” creates research-grounded content like books, videos and a caregiver guide to help children, parents and guardians talk about and process the experience of incarceration.

Julie Poehlmann-Tynan is a professor and chair in the Human Development and Family Studies Department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and an author of the study. She said the study shows there are strong benefits to giving young children developmentally appropriate and honest explanations.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“That can include (saying) something like … ‘We think that maybe your parent broke a law which is a grown-up rule and … we’re waiting to find things out,’” she said. “You can go into a little bit more detail, but not going into detail about the crime or why.”

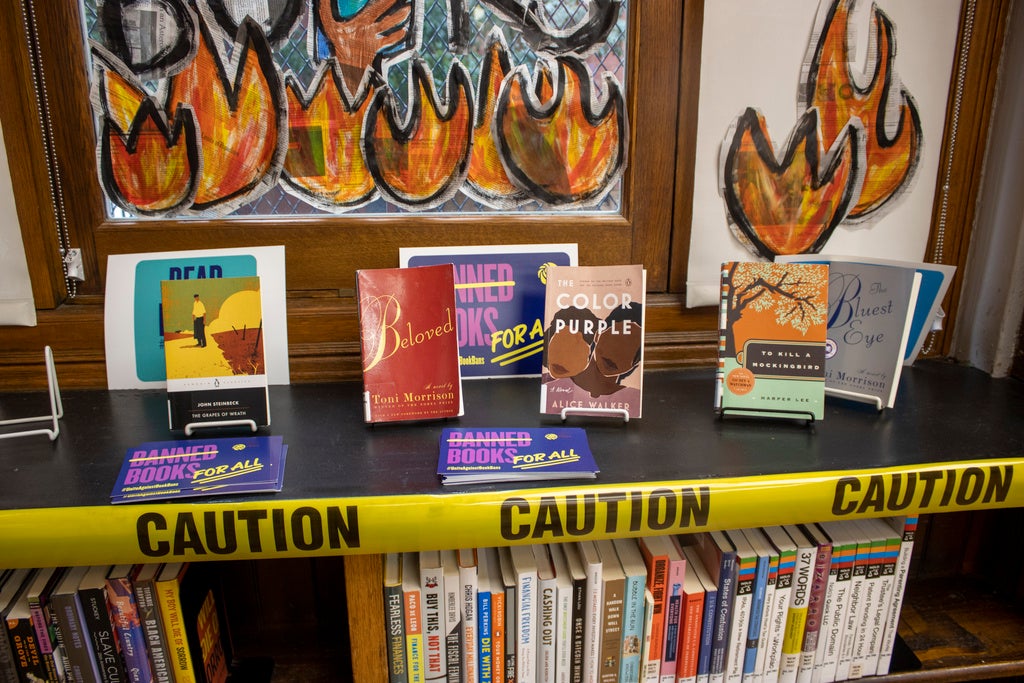

At least 5 million children (about 7 percent) in the United States have a parent who has been incarcerated at some point, according to a 2015 report. Studies show that these children experience more psychological and behavioral problems and have higher odds of entering the criminal justice system.

The Sesame Workshop materials have been available since 2013, and the study started shortly after, Poehlmann-Tynan said. Researchers randomized 71 children — all ages 3 to 8 with a father in jail — and their caregivers into two groups, one exposed to the Sesame Workshop materials and a “waitlist control group,” which would receive the materials at a later point.

They observed the children during a visit to the jail, from start to finish, and then followed up with the child’s caregiver over the phone two weeks and four weeks later.

The most positive finding, Poehlmann-Tynan said, is that the Sesame Workshop materials helped caregivers find the words to talk to the children and help them be more comfortable. Caregivers reported that when they struggled to communicate, watching the videos helped the children feel more open and free to ask questions.

“I think that was the most important finding of the study — that it really did (does) what we intended and that it really helped people feel more comfortable discussing these issues with young kids,” she said. “Because when highly stigmatized information is kept a secret, sometimes kids become aware that there’s a secret and it makes them feel anxious, insecure.”

Another important finding of the study was that children who were told the simple, developmentally appropriate truth about their parent’s incarceration experienced a more positive visit with the incarcerated parent, Poehlmann-Tynan said.

“So many families, they don’t want to put this heavy information on a child, especially when it’s highly stigmatized,” she said. “They might make a softer story, or they might not say anything. But really what we’re finding is that just being honest can strengthen family communication and security in the kids.”

Poehlmann-Tynan said she wants the children and families who experience incarceration to know that they are not alone.

“There are so many people in our country affected by incarceration that it’s become, sadly, a fairly common experience,” she said. “Another message of the materials is that it’s OK to talk to kids about it and if they ask really hard questions, it’s OK when you don’t know … to say, ‘I don’t really know, but I’ll let you know as soon as I can.’”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.