At the height of the Vietnam War, on the night of the full moon, a baby girl is born along the Song Ma River in her mother’s grave. Her name is Rabbit, and she can hear the dead. In a luminous debut novel, “She Weeps Each Time You’re Born,” Wisconsin poet and writer Quan Barry explores wartime Vietnam through the eyes of a little girl with an uncommon gift.

This is magical realist Vietnam — a land of floating villages, Moon Festivals, and jackfruit trees, where ghosts and spirits linger. As waves of U.S. and Viet Cong soldiers sweep through, burning orchards and emptying villages, Rabbit and her family join the floodtide of refugees on the road.

Reading “She Weeps” is a bit like watching an Ang Lee film — terrible events unfold in a landscape saturated with beauty, where myth and history mingle hypnotically. The lyricism of Barry’s writing doesn’t exactly soften all the deaths, but there’s a certain consolation in the sheer poetry of her language.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

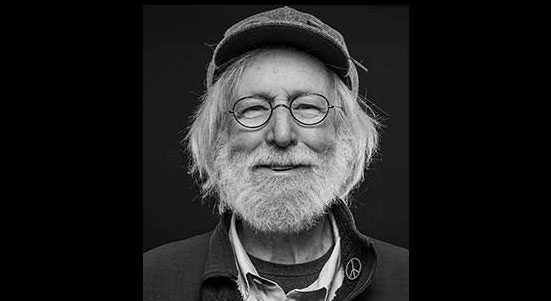

In person, Quan Barry is petite, vivacious, and formidably intelligent. There’s a personal story behind this novel, but it’s not one she will discuss in much detail. In brief, Barry was born in Vietnam in 1973, the year of the Paris Peace Accords and the withdrawal of American troops. She arrived in the U.S. as an infant, was adopted and raised on Boston’s North Shore, and didn’t return to her birth country until she was in her 20s.

Knowing that, it’s hard to read “She Weeps” without thinking about lost mothers and wandering daughters and women who live in more than one world.

This April will mark the 40th anniversary of the Fall of Saigon — Black April, as it’s known to many Vietnamese refugees. It’ll be an occasion for media coverage and a host of new fiction and nonfiction releases. But, “She Weeps Each Time You’re Born” offers a less familiar and more magical take on a country whose history we only think we know.

Below is a transcript of a conversation with Barry:

You’ve given your character Rabbit an origin story that’s like something out of a myth. Where did it come from?

There’s a long tradition of ghost stories in Vietnam and this is one of them — the story of the mother of a baby born in a grave. I read it more than a decade ago and I’ve been obsessed with it for a long time.

I’ve read that she was also inspired by a famous Vietnamese psychic?

I was in Vietnam in 2010, rambling around the country with these Vietnamese guides I had toured with before. One day, we stopped to visit a memorial to the dead. The caretaker lived in a small house next door and she invited us in. I don’t speak Vietnamese, but she told my translator that she was very excited because a woman named Phan Thi Bich Hang was going to be visiting. So, of course I asked “Who is Phan Thi Bich Hang?” and it turns out that she is Vietnam’s official psychic. The story is that when she was a child she was bitten by a rabid dog and when she came out of her coma, she could hear the voices of the dead. She’s the psychic the Vietnamese government uses when they need to find the remains of soldiers or important historical figures, or mass graves. And so Rabbit is based not on her, but on the idea that in a country like Vietnam, a Buddhist country where ancestor worship is really important and where 3 million civilians were killed during the American war there, it’s really important for people to be able to communicate with their lost ones.

Rabbit can speak to and hear the dead. She also can guide them. What exactly is her relationship with the dead? What do they want from her?

They want to be acknowledged. They want their stories to be heard. The dead tell her things and she simply says “I hear you,” and that’s enough for them. I see her role as being a person who listens.

You told NPR’s Scott Simon recently that you think of Rabbit as the spirit of Vietnam itself.

I do. Because she can hear the voices of the dead, so she can hear the history of the country. Through her, we get stories going all the way back to the French colonization in the 1800s and even to the history of the emperors before them. You know, often when Americans think of Vietnam, we only think about roughly 1963 to ‘75, the period of American involvement there. We think of “Apocalypse Now” and other war movies, and that’s it. And yet, Vietnam has been around a very long time and has a very rich history. So in many ways, I wasn’t interested in thinking about the American War in this book. I was interested in thinking about everything else.

You were born in Vietnam, right?

I was. I was born there in ‘73 and I left in ‘74, so I have no memories of Vietnam in the 70s. I didn’t see it again until my 20s.

What was it like for you to go back, and why did you wait so long?

I lived in Japan in ‘92 as an undergraduate, and that was the first time you could go back as an American. Vietnam didn’t open its doors until the early ‘90s. At that time, it was tricky for an American to get a visa, so I traveled mostly in other parts of Asia. When I first went to Vietnam, honestly, it was sort of just another landscape. It wasn’t like a homecoming in any kind of way.

How come?

I think because growing up, I didn’t feel particularly Vietnamese. And I don’t look particularly Vietnamese. I am Vietnamese, I’m not trying to distance myself from that, but it’s not an everyday part of my life. I’ve been there four times and I’m compelled by it, but I don’t feel a homecoming kind of experience when I go there.

You said Vietnam is a country with a rich ghost story tradition. Are they any different from the ghost stories people tell in the West?

Well, to my mind, they tend to be more poetic. Ghost stories in the West tend to be trying to scare you. And Asian ghost stories often aren’t like that. You know right from the outset that someone’s dead, whereas in a Western ghost story you find out at the end: “Aaaaaah, the hook on the car door!” or something like that.

Maybe because in the West, there’s something horrifying about being dead, but in a Buddhist culture, it’s not as scary.

I think that’s true. Spirits in general are much more present in certain Asian cultures. You have an altar in your house, you make sure the rice bowl is full, you have photographs of your ancestors around. The idea is that the dead are very much with us and aren’t considered inherently scary.

Is that because of the Buddhist concept of rebirth?

I think that ties into it a great deal. Because things are seen as cyclical. It’s the idea that the spirits are with us, that we ourselves will become spirits, and that we’ll come back.

I’m curious about how that plays out in a country like Vietnam where there’s been so much death from war, atrocity, and displacement. Do the Vietnamese deal with all that death differently than we might in the West?

I’m not sure, but I did hear a story on NPR many years ago about the cottage industry of psychics that’s sprung up in Vietnam. This was a story about people wanting to find remains of loved ones, or to know what happened to them, or even to communicate with them. Phan Thi Bich Hang is the official psychic of Vietnam, but my understanding is that there are many, many others.

That makes me think about how some landscapes feel haunted. Like Gettysburg, in this country. Or Wounded Knee.

Yeah, and I think of Normandy. I do think the way the West deals with death is very different. We set up these specific places, put all the crosses in one place. We cordon off our grief, relegate it to certain days or occasions — whereas in Vietnam, it’s the entire landscape. It feels more all-pervasive.

If that’s the case, then do you think the Vietnamese have accepted and processed the war more thoroughly than people in the U.S.?

I can tell you that when I first started going to Vietnam as an American, I assumed I would get looks or that there’d be some hostility, but there wasn’t. People find out you’re American and they’re like, “Hey, that’s great!” I remember once my guide took me to meet a man who was in his 90s who’d been a member of the Communist Party for more than 50 years. This was during Barack Obama’s first run for the presidency, and I had all these Obama stickers I was giving out. I gave one to this 90-year old Communist and he was so excited to get this sticker! I think for Americans the question is, what have we learned from Vietnam? All those people were killed and it was horrible, and I don’t think we’ve made peace with it. And it’s not that the Vietnamese have made peace with it, but they’ve moved on.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.