On a playground across the street from Lake Wingra, a couple dozen children are toddling over the snow, bulky in their coats and snow pants. A teacher opens a shed and distributes toys. One child wants to play with a toy bulldozer.

“I want a Bobcat, I want a Bobcat!” he cries.

It’s outdoor time at the St. Mary’s Hospital Child Care Center in Madison.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Kristine Kok runs the center; she apologizes for her cluttered office, explaining that lately, she’s been in the classrooms teaching.

“Because I don’t have anyone to hire!” she said.

Children play on the snowy playground at Saint Mary’s Hospital Child Care Center, where 60 percent of the enrolled families are employees of the hospital and 40 percent belong to the community. Phoebe Petrovic/WPR

Kok has had a teaching position posted for seven months. She could actually use two more teachers, but she can’t even find the one.

Kok has worked at St. Mary’s Child Care Center for 25 years and has been director for the last three. During her tenure as director, she has seen the number of child care workers plummet.

“For the longest time, when I was here as a teacher, we were very stable,” she said. “And I think now, well now why are we not stable when I’m in this position? And it’s a sign of the times.”

Center directors, like Kok, report the shortage of child care workers has become more acute in recent years.

The growing shortage in workers reduces the availability of care. Over half of Wisconsin children live in a “child care desert,” meaning there’s only one slot of licensed child care for every three children, according to a Dec. 2018 report by the national, nonpartisan policy institute Center for American Progress. The report specified that several counties including Washburn, Sawyer and Iron, had zero licensed child care providers at the time the data was collected.

Leaders in the field, including Audra Weiser, early care and education director at The Parenting Place in La Crosse, report encountering parents struggling to find and accept jobs because they can’t find adequate child care.

Ironically, the “times” that Kok references — that makes it so difficult to find qualified teachers — is a good economy with low unemployment. Ruth Schmidt is the executive director of the Wisconsin Early Childhood Association (WECA). She said the state’s workforce depends on child care.

“And yet it’s one of these sort of odd scenarios where the stronger Wisconsin’s economy is, unfortunately, the harder it is to keep people working in early childhood programs,” Schmidt said.

That’s because benefits are poor and wages are low.

Just 17 percent of teaching staff are both eligible for and receive health insurance provided by their employers, according to WECA’s 2016 workforce study. Only half receive paid days off.

In Wisconsin, the average child care worker earns $10.33 an hour. That’s classified as a “poverty wage,” meaning that even with year-round, full-time work, it’s not enough to keep a family of four out of poverty.

Yet child care teachers are, on average, more educated than the typical Wisconsin worker. That same study reports 22.5 percent of early childhood teachers have an associate’s degree, compared to 11.8 percent of the Wisconsin workforce; 27.1 percent of teachers have bachelor’s degrees, compared to 20.9 percent of the Wisconsin workforce.

That same study reports the median wage for Wisconsin workers with a high school diploma is around $13.60 per hour. Yet the average child care teacher with a bachelor’s in early childhood education makes $12 an hour — less than a Wisconsin worker with solely a high school diploma, and nearly half the overall median wage for a Wisconsin worker with a bachelor’s degree.

Graph courtesy of the Wisconsin Early Childhood Association

“I actually had a conversation with my dad the other day; he has worked in a factory his whole life. He actually was really aghast at what my teachers make having a bachelor’s degree, an associate’s degree,” said Angie Wells, child care program director for the Coulee Children’s Center in La Crosse.

Recent changes to regulations have also put increased educational and economic demands on teachers and centers.

Wisconsin’s quality rating and improvement system, YoungStar, incentivizes stricter staff-to-child ratios. State law requires a certain ratio of adults for each child in a classroom, which puts limitations on how many students a center can afford to enroll and how many teachers a center can afford to hire. YoungStar also encourages higher credentials for teaching staff.

The “tension between the demand for more education within the child care teaching workforce and the very low pay-off for that education” is a central challenge in the industry, according to WECA.

“A lot of people in the public just say, ‘Why can’t you pay teachers better?’” said Wells, who needs a second job to supplement her director’s income. “I would love to. I would love to be able to pay my teachers $15, $16, $17 an hour or even higher.”

The problem is, child care centers can’t afford to pay their teachers more.

Abbi Kruse, founder and executive director of The Playing Field in Madison, said 89 percent of their revenue goes directly to staff salaries and benefits.

On top of that, centers have large expenses — building costs, insurance, supplies, food — and they’d have to charge families higher tuition.

“Anytime we raise tuition rates, we’re taking that directly out of the pockets of families,” said Kruse. “Are these teachers worth more? Absolutely. Can families afford to pay more? Absolutely not.“

Unsustainable Salaries

The government does not support child care in the same way it supports K-12 education.

“Those of us that teach here are not getting paid anywhere near what a public school teacher would make,” Kok said.

Schmidt, of WECA, calls child care a “broken market.”

As a consequence, all over the state, child care directors are struggling to find and keep qualified teachers.

Licensed group centers, like Saint Mary’s, provide “care for the overwhelming majority of children in the state” and employ 88 percent of the state’s child care teaching staff, according to WECA.

Schmidt said over the past 15 years, in-home family providers — meaning individuals who provide regulated child care out of their homes — have dropped by 60 percent. In recent years, Schmidt and her colleagues have begun to see turnover not just at the level of teaching staff, but directors as well.

Graph courtesy of the Wisconsin Early Childhood Association

Kok wondered aloud what motivates people to go into and stay in the child care field when compensation is so poor.

“Passion is one thing. But I also need to be able to live. I need to be able to pay my bills,” Kok said.

About three out of 10 teachers leave their jobs each year, taking positions with better pay and benefits at public schools or retail chains like Kwik Trip and Walmart.

“I call it the rock polishing effect,” said Sue Schimke, who has worked in child care for more than 35 years and currently serves as the director of Little Turtle’s Playhouse in Beloit.

She said she’s mentored countless young teachers over the years who, shortly after receiving training and education, leave her center — or the profession altogether.

“Once they get their degree, they’re shining so brightly that somebody’s ready to take them and they go onto a job with benefits and better pay,” Schimke said.

Jillian Clemens is one of the teachers who left. She taught preschool for nearly a decade, after receiving her bachelor’s in early childhood education from the University of Wisconsin-Stout and landing a job right out of college. But she soon realized her salary wasn’t sustainable.

“Because I loved it and I was passionate about it, I at first was like, ‘OK, I’ll figure this out. I’ll get a second job because this is what I want to do. This is who I am. This is literally a part of my person.’ I could feel it in my bones that I was going to be a teacher for the rest of my life,” Clemens said.

But eventually, she couldn’t make the numbers work.

“I had to make the really, really, really hard and painful decision that I just couldn’t afford to keep doing this job anymore and to get the work-life balance that I really needed for my own well-being,” Clemens said.

She now works on programs and policy related to children and families and she’s getting her master’s degree in human ecology at UW-Madison. But she said everyday she misses the children, especially how they learn.

“They’re like planting all these seeds for themselves, and they’re learning, and it’s just so — it’s so cool,” said Clemens.

The First 5 Years

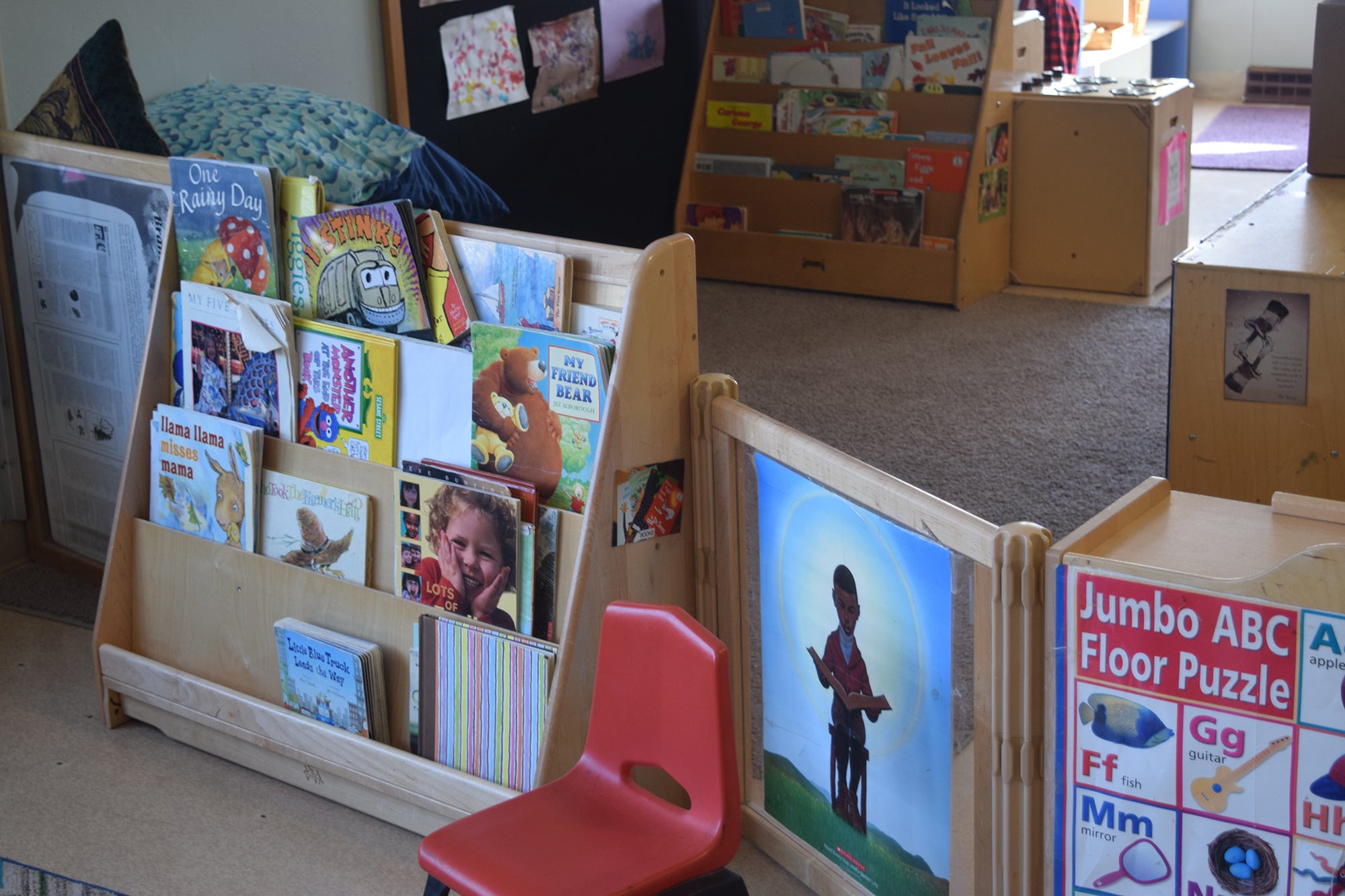

At Saint Mary’s child care center, run by Kok, children sing their ABCs and learn important social-emotional skills through play.

Research shows a child’s first five years are crucial for brain development; what young children learn and experience stays with them for life.

“One of the things that I always say is if people really understood what is happening in the brain in the first five years, our infant-toddler teachers and our preschool teachers would be the highest paid folks around,” said Kruse, of The Playing Field.

Kruse’s center serves integrated classrooms of young children with stable housing and those experiencing homelessness, who often experience trauma that can affect their development.

Maya Hamilton, 5 months, spends her days in the infant room at Saint Mary’s Hospital Child Care Center, with seven other infants and two primary teachers. Her older brother Chase Hamilton also attends the child care center. Phoebe Petrovic/WPR

“We actually call our teachers brain builders. We got T-shirts this year with all different kinds of job titles, like ‘cerebral architectural specialists,’” said Kruse. “They’re actually building the architecture of young brains by the interactions that they have with children every day, and if we really understood that as a country, we wouldn’t devalue them in terms of salary or in terms of the level of respect we give the role.”

Child care professionals like Kruse, Clemens, Schmidt and others say, teachers’ compensation doesn’t match the science. They blame the field’s economic model on societal indifference, saying that the general public does not understand or respect the field enough.

“Times are changing, but I don’t think that early childhood has been looked upon as education,” said Wells of the Coulee Children’s Center.

“Early childhood is not recognized as something more than just babysitting, taking care of kids for the day,” Kok said.

And right now, child care providers are paid like babysitters, not like teachers. Until that changes, more teachers will likely leave the profession, and more centers will have to turn families away or shut down altogether.

Amelia Schmelz (2 years and 3 months) and Chase Hamilton (2 years and 8 months) play with headphones in the older toddler classroom at Saint Mary’s Child Care Center, which has had a teaching position posted for seven months. Phoebe Petrovic/WPR

For longtime child care professionals, like Schimke, the consequences are grave:

“How do we get the business world to understand if we don’t take care of the children, people can’t come to work, and if we don’t have good people to care for the children, we’re letting our world fall apart?”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.