Canada geese are being euthanized as part of a yearslong effort to restore wild rice in the St. Louis River that flows into Lake Superior, but the practice has drawn opposition from animal protection groups.

The St. Louis River estuary that runs along Duluth and Superior was once home to abundant wild rice beds throughout many of its bays. But industrial pollution, habitat and land use changes over decades have led to its decline.

The site is one of 43 areas that were designated by the U.S. and Canada as the most polluted hotspots on the Great Lakes in 1987. A mix of state, federal, local and tribal partners have been working to bring back wild rice as part of ongoing restoration efforts on the river.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

However, Canada geese have hindered efforts to establish large beds within its bays, according to David Grandmaison, the estuary’s wild rice project coordinator for the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

“They are coming into these rice beds at a time when the wild rice is pretty susceptible and pretty fragile as it’s kind of transitioning from the floating leaf to a standing growth stage,” Grandmaison said. “They come in and they nip it off at the waterline, essentially, or a couple inches above the waterline. That wild rice, oftentimes, will not then grow to produce seed.”

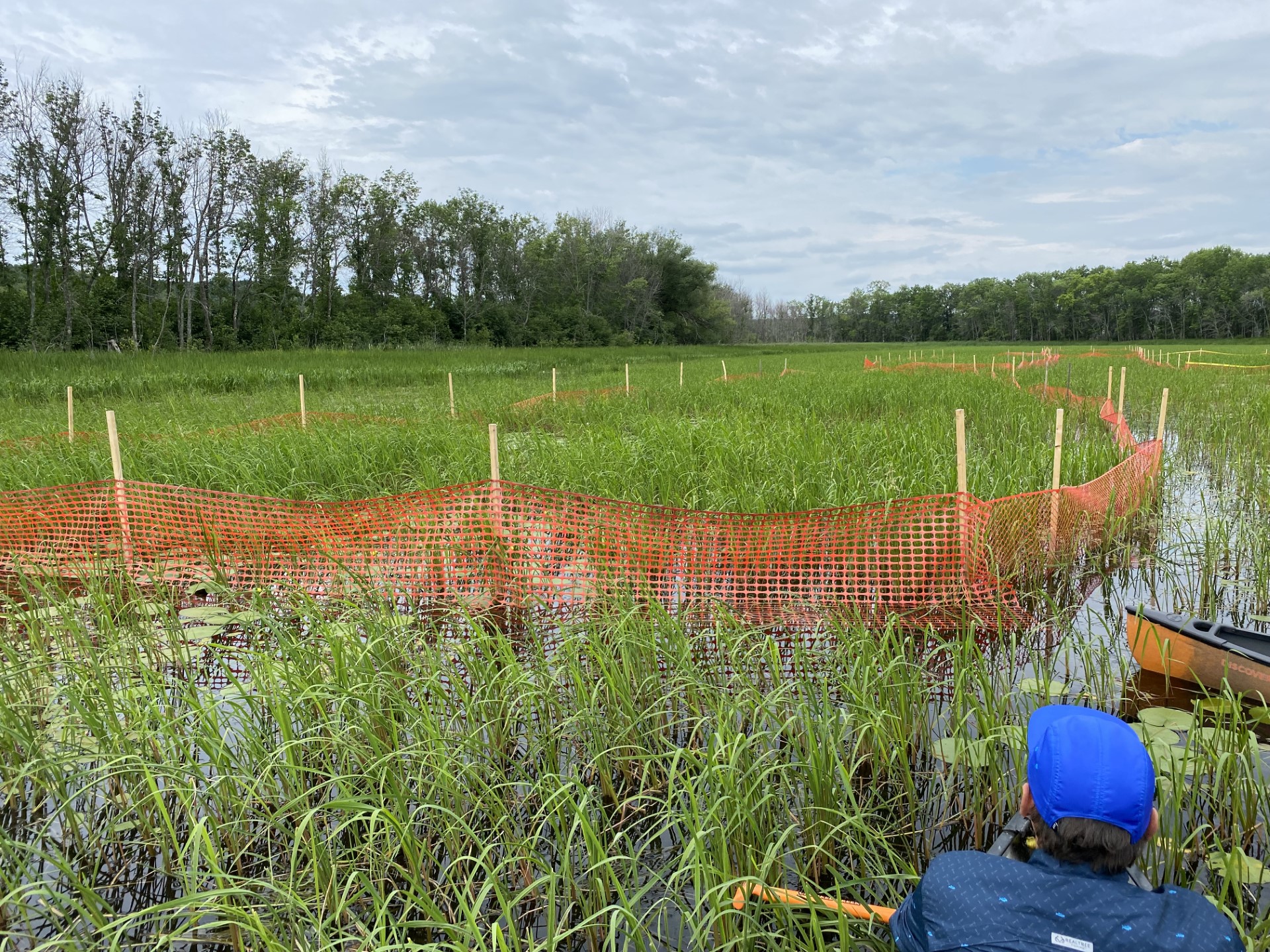

To reduce pressure on the plants, partners tried a variety of nonlethal methods to deter geese. They used swan or coyote decoys, Mylar tape to protect wild rice, and hazed or harassed geese. They’re also using fenced off areas known as exclosures to protect wild rice or Manoomin, according to Tom Howes, natural resources program manager with the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.

“We just expanded the geese exclosures in the bays that were showing the most promise, and then started going down the road of exploring actual geese removal because that really is the most effective thing,” Howes said.

In 2021, the Wisconsin DNR began using goose “roundups” to manage geese. A roundup involves surrounding juvenile and adult birds with fencing and herding them into crates that are put into chambers. The geese are then euthanized using carbon dioxide in line with American Veterinary Medical Association guidelines to ensure they’re disposed of in a humane way.

Dan Hirchert, state director for USDA Wildlife Services in Wisconsin, said the method is a last resort to manage geese. He said they would ask people to try fencing, a vegetative buffer, and other options like those tried by resource managers working in the St. Louis River.

“We’re trying to make the best out of, I guess, a bad situation of having to do this at all,” Hirchert said. “We would just as soon not have to do this, but you have to be able to use some of these spaces, as well as try to recover the wild rice.”

Across Wisconsin, Hirchert said the agency is removing around 1,500 Canada geese on average each year while current estimates suggest there are millions of resident Canada geese in North America. During the late 1990s, wildlife regulators helped a handful of communities with roundups. Over time, he said they now talk with 50 to 60 communities about using the method to deter geese from parks, beaches, and other areas where they have reduced public use or contaminated water quality.

“This is the first time that we’ve permitted activities for habitat management or, in this case, a wild rice resource,” said Brad Koele, DNR wildlife damage specialist.

The state issued 32 permits this year and 25 permits in 2022 for goose roundups. Communities like Beaver Dam, Balsam Lake, Lake Mills and Oshkosh have used the method to control geese.

Koele said municipalities have the option to test, process and donate geese to food pantries. In some cases, the birds are donated to wildlife rehab centers or used as animal feed.

Even so, the practice has raised concerns among animal protection groups, including California-based nonprofit In Defense of Animals. Lisa Levinson, the group’s campaigns director, helped start the National Goose Protection Coalition in 2019. She said around 25,000 geese are killed every year using roundups, which she views as a cruel and painful method of goose management.

“We don’t even like to call them roundups because they are really goose massacres,” Levinson said. “It is a very traumatic experience for these animals who are highly bonded to each other, and imagine they’re killing these families while the babies are very young and the parents can’t fly away.”

The roundups are performed when the geese are molting in June and July. During that time, adult birds are unable to fly and juveniles are in their flightless stage.

Paul Collins, Wisconsin state director with Animal Wellness Action, said in a statement the group is concerned with the use of goose roundups.

“We support non-lethal forms of active management to reduce populations and address concerns about the waste that geese produce,” said Collins. “Addling the eggs of geese, and keeping them in the nest, is a proven way to limit reproduction and keep a lid on numbers of resident Canada geese.”

Levinson added that vegetative buffers along the shore could also help deter geese, which prefer areas with shorter grasses in order to see potential predators.

Linda Cadotte, director of parks, recreation and forestry for Superior, said the city supports all efforts to restore wild rice on land and water. She highlighted attempts over multiple years to address issues with geese through nonlethal measures.

“I applaud all of the other efforts that have taken place prior to getting this to this point,” Cadotte said. “Hopefully, it’s a very short-term option.”

Howes said that’s the goal. Partners are using the roundups as a management tool to promote higher wild rice densities so that the plant can be more resilient to geese grazing on their stems in the future.

He added that wild rice is central to the tribe’s migration story, noting Fond du Lac was once a ricing village. The reservation has five lakes where tribal members harvest wild rice, but he said there are very few wild rice water bodies within a 100-mile radius outside the tribe’s boundaries.

“We have an obligation is what I always tell people,” Howes said. “As Ojibwe people, wild rice has always taken care of us. If you go back to those stories of our migration, we wouldn’t have survived nearly as well or maybe not at all were it not for this sort of gift.”

Despite that, Levinson is doubtful the method will work over time, saying more geese will move into areas where they’ve been removed.

“I know rice is important and I understand its value for the Indigenous people, as well,” Levinson said. “We want to acknowledge that and make sure that we find a solution that is a win-win.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.