Not everyone finds what they’re meant to do in life. But Charles Sheppard did. Friends and family say he truly believed in the value of one veteran helping another, and that’s what he was doing in his role as a peer support specialist with the Milwaukee VA Medical Center.

Charles helped hundreds of veterans as they overcame struggles with addiction and homelessness — challenges he understood firsthand. He got a second chance, and he held on tight, friends say.

His sister Valery Sheppard said Charles was healthy before contracting the coronavirus. He was 61 when he died of COVID-19 in June.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Wisconsin has lost more than 4,000 people to the pandemic. Like many others, Charles had a lot of life ahead of him. More than anything, he loved being a parent to his young son, and he’d just closed on a new home days before falling ill. And though his life was cut short, Charles left his mark.

The Protector

Charles grew up in Chicago with eight siblings. He lost his mom when he was a child, and his only brother died while serving in the U.S. Navy during the Vietnam War. Charles, Valery and their sister Deborah were the babies of the family, Valery said.

Charles took on the traditional big brother role, becoming a protector for his sisters, looking out for them and walking them home from school, Valery said.

After losing their brother, Valery and Charles were apprehensive about joining the military, she said. But it was their father’s experience that swayed them. He’d been in the U.S. Army and loved the comradery.

Charles joined the Navy and Valery joined the Army. She’d done ROTC in high school and settled into military life more easily than her brother. He’d left the Navy by the time she completed her service. When she learned Charles was struggling with addiction, he stayed with her for a while, but Charles worried about being a burden, Valery said.

“Then the next thing I know, I came home one day, and his stuff was all gone. We just lost touch with him,” she said.

But his sisters wouldn’t let him go so easily.

Deborah mounted a search that eventually led to their brother’s sponsor, who was helping Charles on his path to recovery. The sponsor took down Deborah’s contact information.

“About a month later my brother reached out to her to say he was doing good, he was off drugs, he has a place to stay, and he’ll reach out to us in a while,” Valery recalled.

And he did. When he visited the family, Charles’ sisters hugged him and kissed him and told him that his nieces and nephews wanted to be in his life, Valery said.

“And he promised to do better and that’s what he was doing from what I understand,” she said.

‘His Ability To Connect With Others Was So Viable’

Valery said she was glad her brother made his way to the Milwaukee VA, a place he initially went to for help before joining the staff of its homeless outreach program.

Dr. Erin Williams, a psychologist at the VA, was on the committee that hired Charles in 2013. There were lots of applicants, but she remembers he stood out.

“He scored higher than anybody; but if you looked at his resume, did he have all the education? No, he didn’t. But he had an emotional intelligence. His ability to connect with others was so viable,” she said.

In the job, Charles was often the first point of contact for veterans without housing. He helped them find safe places to stay and explained how they could talk to landlords about their past. He always went the extra mile, said his friend Dorothy McCollum, a social worker at the VA.

Sometimes he’d even recommend VA resources to his sister Valery to make sure she was getting the benefits she deserved as a veteran, Valery said.

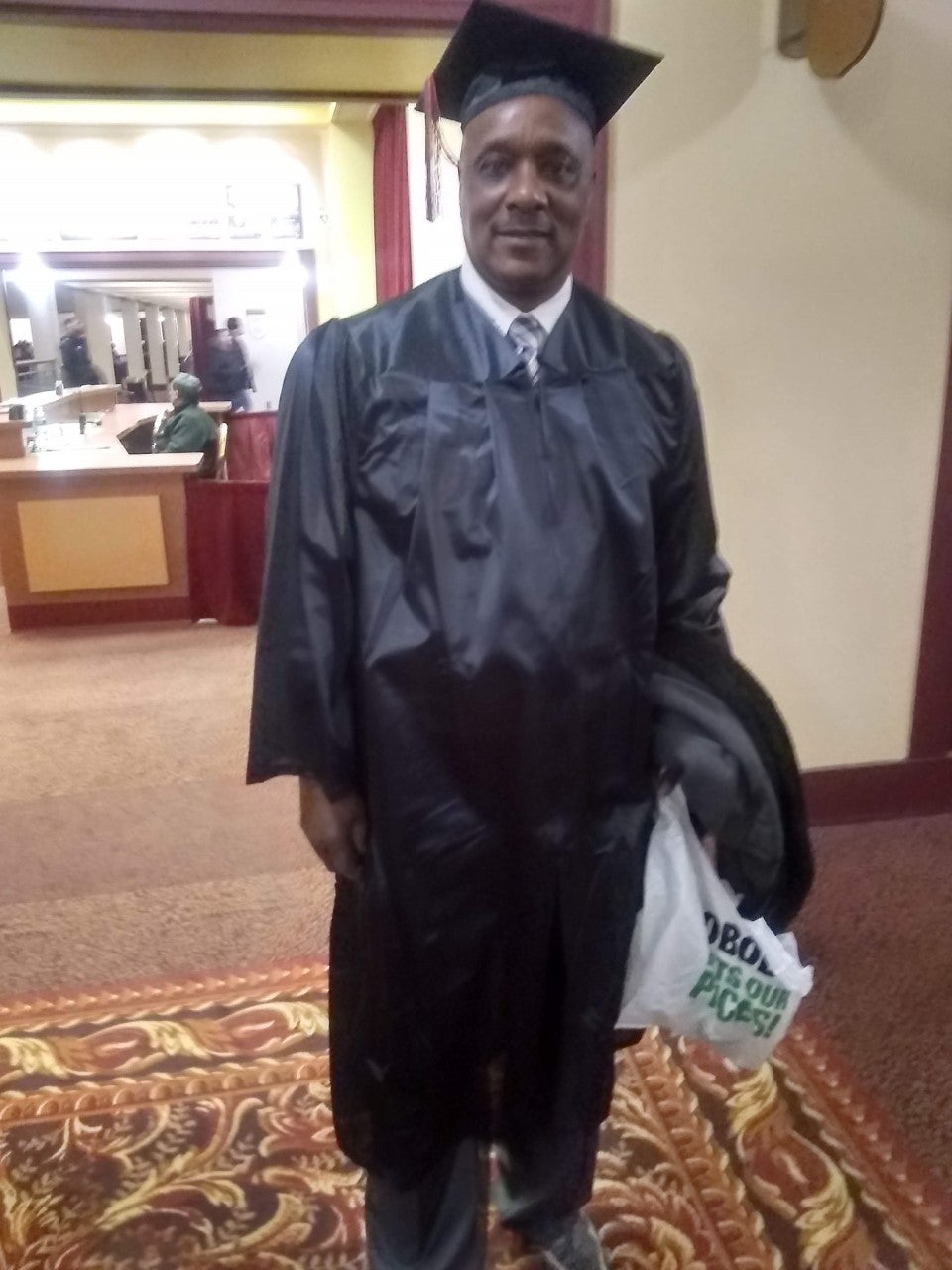

Charles loved to learn and sought out feedback on how to do his job better, Williams said. He earned an associate degree and had plans to continue his education.

“Oh my goodness, when my office was still upstairs from his, he would always be in my office talking about a paper or a class, and his zest for learning was just so amazing. I mean, he was all in, and he needed more. The more information he got, the more information he wanted,” McCollum said.

Though McCollum and Charles became colleagues, they met at Narcotics Anonymous — she’d been clean for years, but he was still early in his recovery, she said. That didn’t stop him from pestering her about attending meetings and speaking. At first, she thought he came on strong, but now she misses his big personality, she said.

“He was so resilient with learning, with appreciating this new way of life and just being so outgoing, so caring and loud and obnoxious. All at the same time,” she joked.

Williams and McCollum will miss other things, too, like their friend’s smile, his pocket full of ink pens, his passion for the Pittsburg Steelers and the notes he’d often scrawl on the dry-erase board outside Williams’ clinic: “CS was here.” Now she keeps a Post-It note on her computer that reads the same message.

Many Veterans Have Struggled Through The Pandemic

The coronavirus pandemic has made it a difficult year for many of the veterans Williams works with.

“When I serve veterans, I use the analogy of an emotional rucksack, and we all have one,” she said. “And you know, rucksacks have pockets and belts that hold heavy loads and can accommodate a substantial amount of gear, but it has a limited capacity. And it can be filled to overflowing, and when it overflows it will impact those nearby.”

This year, it’s impossible not to feel the weight of the pandemic.

Clients who were on ventilators have flashbacks of gasping for air, and other veterans — those who haven’t tested positive for the coronavirus — have considered suicide due to factors, like loneliness, joblessness and debt, she said.

Williams was struck by what she heard from a patient who had COVID-19: Between visits from doctors and nurses, all he could think about was the deadliness of the virus that had put him in the hospital, she said.

McCollum urges Wisconsinites to take the virus seriously. Charles isn’t the only coworker she’s lost to COVID-19, she said.

‘That Was The Joy Of His Life’

Though Charles walked a tough road at times, he never lost his spark, Williams said.

He loved bowling and jazz. McCollum was there when he closed on his first house with a realtor she’d helped him find. He was planning to use it as a rental property after moving into his new home. But one thing he always wanted didn’t come until later in life. His son, Isaiah, was born when Charles was 58.

“That was the joy of his life when he had Isaiah,” McCollum said.

In a memorial article, Isaiah’s mom told the Milwaukee VA that Charles was sick with COVID-19 for a long time, but he often called to check in.

After Charles died, his sisters made a keepsake book for Isaiah with photos of his dad, Valery said. Isaiah will be proud of his father when he’s old enough to understand all that he accomplished, Charles’ family and friends said.

Valery is retired and lives in Florida, but some of her sisters plan to bring Christmas gifts up to Milwaukee for their nephew, she said. They want to stay in his life, and they also know Charles had plenty of friends in Milwaukee who help keep his memory alive. Many contacted Valery and her family to see if they could help after Charles passed.

“Even when they reached out to us, they said, ‘We are doing this because your brother was such a good friend to us, and we wanted to do for him as he did for us,’” she said.

More than 4,000 people in Wisconsin have died from COVID-19. But it’s more than just a grim statistic. That number includes a World War II veteran, a loving grandmother, nuns at a convent, a coach and avid Badgers fan, and a champion for veterans. This week, WPR News and “Wisconsin Life” are bringing you the stories of just a handful of those who have died.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.