Pint-size protesters could be seen outside Wisconsin’s Capitol Tuesday, holding signs and making speeches as a group of more than 100 children, parents, workers and business owners called for the continuation of a child care subsidy program.

Wisconsin’s allocated hundreds of millions of dollars through the pandemic-era Child Care Counts program, which was intended to keep the child care industry afloat.

Thousands of Wisconsin child care centers used the federal grants to partially offset expenses for things like wages, rent, utilities, and personal protective equipment.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

But, with federal funding set to run out by early 2024, Democratic Gov. Tony Evers asked for more than $340 million over the next two years to keep the Child Care Counts program going.

Last week, the Republican-led Joint Committee on Finance rejected that request, and declined to allocate any state dollars for Child Care Counts in the next biennial budget.

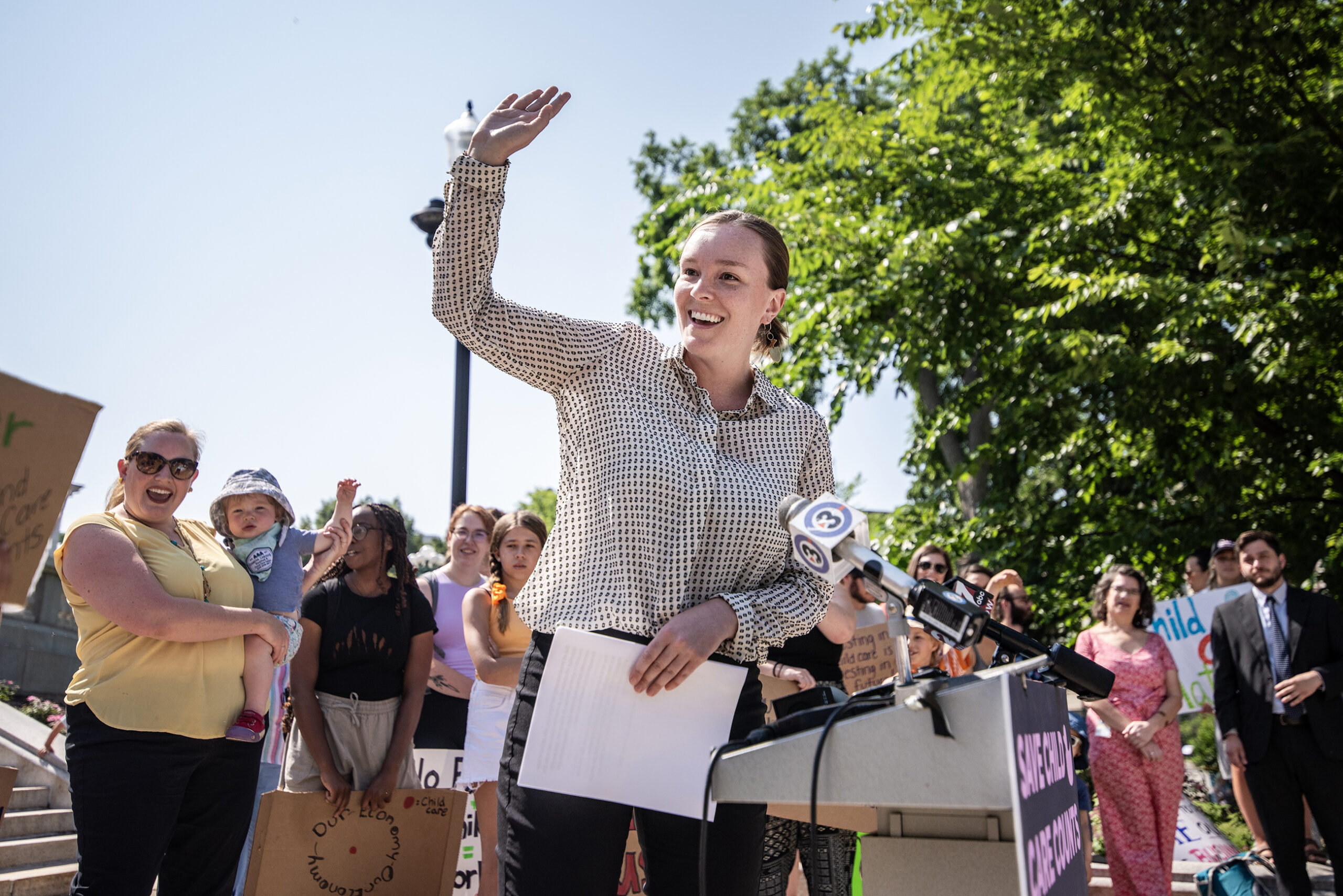

State Assembly Minority Leader Greta Neubauer, D-Racine, said unless that money is added back into the budget, day cares across Wisconsin may be forced to raise tuition or even to close.

“Are you, as parents, gonna have to ask yourself whether you are leaving the workforce, maybe not having more children, having decisions dictated by the availability and price of child care?” Neubauer asked protesters on Tuesday.

In a written statement, Finance Committee Co-Chair Sen. Howard Marklein, R-Spring Green, said the Child Care Counts program would have obligated hundreds of millions of dollars in new spending for what was always intended as one-time federal relief.

“I understand that some child care centers may choose to raise rates in order to stay in business,” Marklein said. “I understand that some families may choose to make different arrangements for their children when rates are raised. But I also recognize, from personal experience, that most parents choose to pay for quality child care to ensure that their children are safe, healthy and happy, even though they may complain about it. Every family chooses their own path.”

Marklein also pointed out that lawmakers on the finance committee earmarked $95 million for existing child care programs. That includes $45 million in aid to low-income families though the Wisconsin Shares program and $15 million that could be spent on a revolving loan fund, so that child care facilities can make upgrades.

Rep. Mark Born, the other co-chair of the budget committee, likewise defended the committee’s actions.

“The Republican motion provides targeted support for child care affordability and accessibility by increasing financial support for the families that need it most, funding several initiatives to increase child care capacity and more than doubling funding for child care provider recruitment and retention,” the Beaver Dam Republican said in a written statement.

The full Legislature would still need to approve the child care budget along with the rest of the two-year spending plan.

At Wisconsin’s GOP Convention Saturday, Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, R-Rochester, told party activists that lawmakers are prioritizing plans to address child care costs, though he didn’t give specifics.

“Child care in Wisconsin is a problem for families,” Vos said. “It’s not something that the taxpayer should be responsible to pay for. But the availability and the accessibility to child care for so many parents that have made the decision to have two parents work is something the Legislature is working on.”

But Senate Minority Leader Melissa Agard warned protestors the consequences for parents and businesses would be “dire” unless the state steps in to fund Child Care Counts.

“There is a child care cliff looming in front of us in the state of Wisconsin,” the Madison Democrat said.

About 27 percent of Wisconsin child care directors reported they would have closed without the Child Care Counts grants, according to a fall 2022 workforce survey by National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Once those grants end, over 60 percent of those surveyed predicted they would need to raise tuition. And more than a third of the respondents said they’ll be forced to cut pay.

The child care industry was “already fragile” and the pandemic only intensified those financial pressures, a University of Wisconsin-Madison study of the Child Care Counts program notes.

“Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, however, many Wisconsin families did not have access to or could not afford such services, and low wages and slim profit margins made it difficult for providers to thrive,” read the study, which was supported by a contract between Wisconsin’s Department of Children and Families and the UW’s Institute for Research on Poverty.

Nationally, the median annual pay for a child care worker is just $28,520, according to 2022 data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Low pay is part of the reason why Sierrena Taylor-Seals said she is leaving her job at the Big Oak Child Care Center in Madison. She already has a master’s degree in education, but plans to pursue a doctorate in applied computer science, so that she can learn more about the technological side of the education field.

Taylor-Seals said she only stopped living paycheck-to-paycheck from her day care job because of a bonus made possible by the federal grant program.

“Child Care Counts has allowed me to basically barely survive,” she said. “I’ve been barely able to manage.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.