A new federal report says climate change is expected to have wide-ranging impacts on the Midwest, including declines in agricultural production and biodiversity. The latest volume of the Fourth National Climate Assessment, NCA4, also details the threats climate change may pose to the region’s economy through increased flood risks and impacts to human health with degrading air and water quality.

A team of more than 300 federal and outside experts compiled the report. Researchers found rising temperatures and more frequent, intense rains are likely to reduce agricultural production in the Midwest to levels seen in the 1980s by 2050.

The report reiterates many of the findings compiled by an agriculture workgroup with the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts, including more soil moisture, erosion and favorable conditions for pests. Chris Kucharik, agronomy professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said frequent, heavy rains will make it more difficult for farmers to control runoff.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“It’s going to make it more difficult for them to manage inorganic fertilizers like nitrogen that they apply to their crops, as well as manure spreading,” said Kucharik. “Unfortunately, heavier rainfall, more erosion creates a scenario of more leaching of things like nitrate to groundwater. With more surface runoff, we’re likely to see more phosphorus and nitrate end up in surface waters contributing to the water quality problems that we have ongoing.”

Some farmers are already adapting to climate change by trying to reduce manure concentrations through split applications or using cover crops to prevent erosion and runoff. Even so, growers will still contend with decreased production in the face of rising temperatures.

Scientists say commodity crops like corn could see reduced yields of 5 to more than 25 percent across the Midwest although some areas could see gains. Scientists also project that average annual 5-day maximum temperatures in northern Minnesota could reach levels just under those currently seen in southern Missouri.

“We’re on the northern fringes of a primary global region that grows a lot of corn and soybeans. I think that those are going to be part of our landscape, but it might become more and more difficult then to sustain the high yields moving forward given the growing conditions,” said Kucharik.

He also noted rising temperatures may lead to more heat stress on animals, potentially decreasing milk production. Warmer weather may also increase demand on water for irrigation, such as in the Central Sands region of Wisconsin.

Biodiversity And Ecosystems

The report’s scientists warn the rapid pace of climate change has the potential to accelerate the decline or extinction of species, as well as degrade ecosystems. As species change, the landscape may be less able to act as flood control and/or provide the necessary environment for crop pollination. Over the last half-century, Wisconsin forests have already seen the impacts of rising temperatures and changes in precipitation through a shift in the distribution of plant species.

Researchers compared 78 understory plant species and their location to shifts in climate change across Wisconsin from the 1950s to the 2000s, according to Don Waller, plant ecologist and botany professor with UW-Madison. The findings, published in 2016, found species shifted northwest by about 30 miles or more.

“Except that most species are not able to really keep up with the rate of climate change that has already occurred,” said Waller. “This is a concern to us because they expect climate change to accelerate over the next 50 to 100 years. The fact that we already see species in a sense trying to shift their climate but not being able to keep up, we’re concerned that this lag may increase in the future.”

Waller said plants like baneberry and rattlesnake fern were able to keep up with the shifts in climate. However, he noted that species like enchanter’s nightshade and meadow rue were not as able to adapt.

“Some of the lag may represent a failure of the plant species to keep up and some may reflect the fact that they didn’t have to move quickly because the forests were shadier and a little more humid than areas outside the forest so the pressure wasn’t as intense,” he said.

Waller said it’s unclear what climate shifts may mean for plant species in Wisconsin forests. But, he said it may lead some species to simply “drop out” as they’re unable to keep up with changes in climate.

Vulnerable Communities

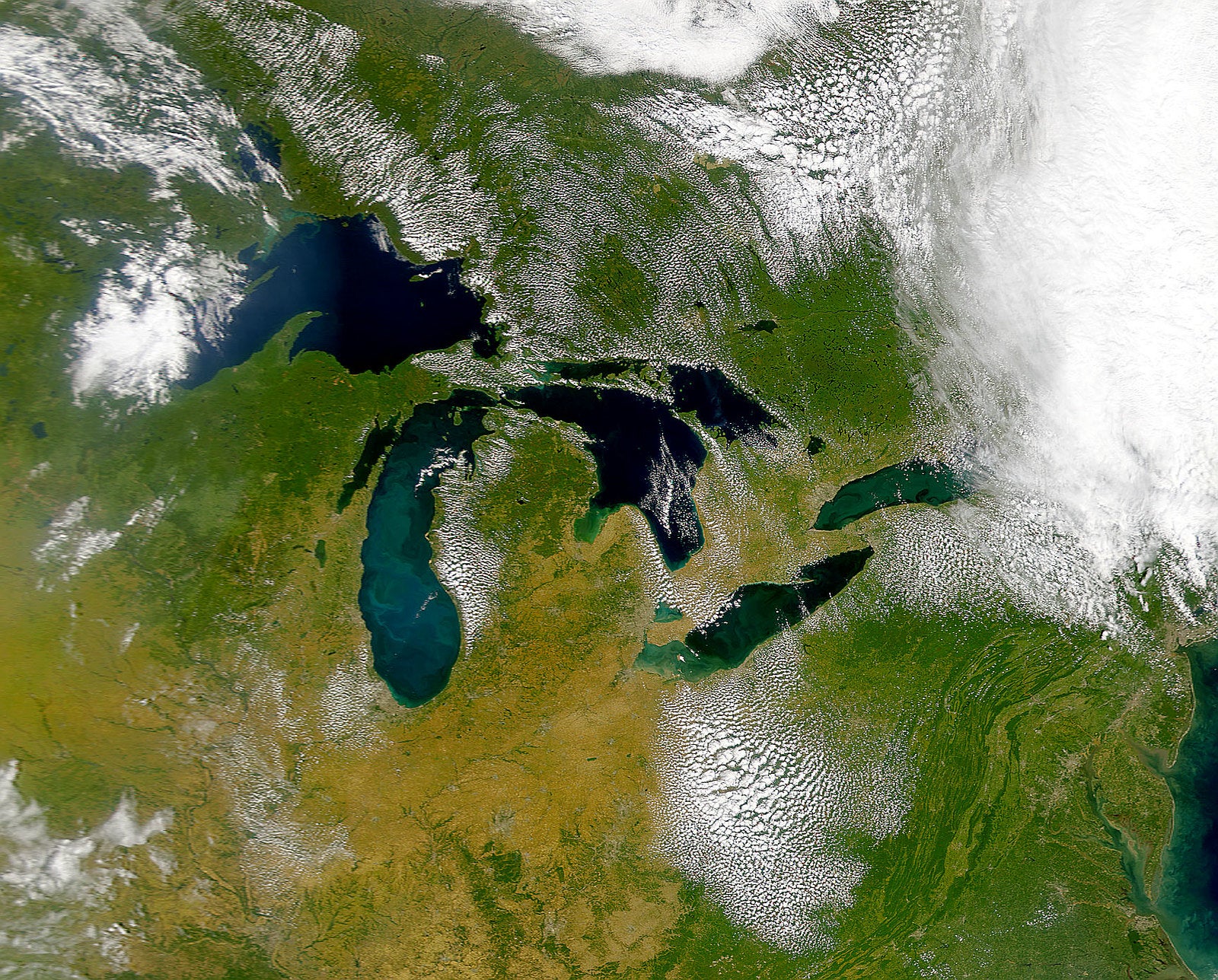

Scientists also warn that tribal communities are among groups that are most vulnerable to climate change. Ojibwe tribes in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan practice their rights to hunt, fish and gather under treaties with the federal government. Warming temperatures and heavy rains can affect the natural resources they rely on to thrive, as well as cultural practices and traditional life ways.

The Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission has been working on a climate vulnerability assessment of 60 species or beings important to its 11 member tribes in Wisconsin, Michigan and Minnesota. GLIFWC climate scientist Hannah Panchi said they’ve identified the snowshoe hare and wild rice as some of the species most vulnerable to climate change.

“If you have extreme precipitation events, that can cause a complete failure in the rice crop if it happens at a certain time. The plants are really sensitive in the floating leaf stage,” she said. “A lot of people depend on wild rice for food and it’s really integral to their culture.”

Tribes are combining science with traditional ecological knowledge to respond and adapt to climate change. GLIFWC traditional ecological knowledge outreach specialist Melonee Montano said tribes are also witnessing declines in walleye, which thrive in colder waters.

“As Anishinaabe people, we are what is in our environment, everything around us. That’s basically how we’ve learned to be, how we’ve learned to live, how we’ve learned all of our different values,” said Montano. “The worry is that some of our young ones won’t actually be able to be as connected to those activities we’ve done for many generations.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.