Comedian Rich Hall talks about a lifetime of groundbreaking comedy. Filmmaker Julie Seabaugh on her Vice TV documentary, “Too Soon: Comedy After 9/11.” And acclaimed film critic Ian Nathan takes us inside the time-bending films of director Christopher Nolan.

Featured in this Show

-

Rich Hall's memoir 'Nailing It' explores the key turning points in his life

Editor’s note: This story contains videos that may not be appropriate for some audiences.

Rich Hall is a multi-award-winning comedian, author and musician. He wrote for David Letterman and was a frequent guest on both Letterman’s morning show, “The David Letterman Show” and “Late Night with David Letterman.” Hall was also a cast member and writer for “Saturday Night Live,” “Fridays,” and “Not Necessarily the News.” In the late ’90s, he created a character named Otis Lee Crenshaw — a redneck jailbird from Tennessee. For his performance as Otis, Hall received a prestigious Perrier award at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in 2000.

Hall moved to the UK in 2001 where he continues to perform stand-up and his own brand of musical comedy. Rich recently released a memoir called “Nailing It: Tales from the Comedy Frontier.” The book explores real-life experiences in which Hall really had to nail it. And he did — every single time.

Journalist and novelist Carl Hiassen says that it’s rare for somebody to be as funny on paper as they are on stage.

So what is Hall’s secret to getting the laughs onto the page?

“When you’re a stand-up comedian and you have an audience who immediately tells you if something works or doesn’t, that’s a pretty good bellwether for your comedy working,” Hall told Wisconsin Public Radio’s “BETA.” “But when you’re writing it, you really have to fall back on what made you want to be a comedian in the first place. I think I’m funny.”

From obit writing to dog baptisms

Hall started his career as a journalist for the Knoxville News Sentinel, where he wrote the publication’s obituaries.

“I was writing obituaries at midnight in a big, empty building with nothing but an old typesetting room over my head. This is after studying journalism at Western Carolina University. This is after editing a newspaper,” Hall said. “And the next thing I know, I’m just writing up dead people that I don’t even know. And that just did not last long.”

Brother Jed Smock proselytizing in Moores Switch Columbia, Missouri, in 2007. Mike Tigas (CC BY-NC 2.0) “It was a sort of weird turn of events that made me look out the window one day and see a campus preacher named Jed Smock, who weirdly only passed away a couple months ago and was still up to his dying day, going around the campuses and evangelizing,” he continued.

After he saw Brother Jed Smock proselytizing, Hall went to the university library and kept thinking about what he had witnessed.

Smock would get the crowd together and really antagonize people, which would draw even more people, Hall explained. In a matter of minutes, Smock would have around 200 people gathered around him.

Hall was inspired by Smock’s ability to heckle.

“He was better than any comedian I’ve ever met at dealing with hecklers, because that’s what he did, you know? And he knew it. He knew how to out-Bible anybody in the audience,” Hall said.

Hall said after witnessing Smock, he thought about what it’d be like to rile up a crowd of that size for 10 or so minutes, and then reveal the bit was all a joke.

“I had no real inkling that this would turn into a comedy career. It just seemed to me I could go out there and after 10 minutes, suddenly I’m pulling out this giant album that says ‘God’s Greatest Hits.’ That’s why God is everywhere,” he said.

Hall worked as a street performer, creating improvisational sketches on various college campuses.

“And then I started baptizing dogs. I’d get dogs out of the crowd. And it was one of those things comedically when you know that you have a pay off. And now all we have to do is sort of reverse engineer it up to that point. And the payoff was I could exorcise a dog — ‘exor’ not ‘exer.’ If you poured a pitcher of water over their head and then say, ‘Denounce Satan,’ what are they going to do? They’re going to shake like crazy. And it worked every time. It was great,” Hall recalled.

David Letterman and Otis Lee Crenshaw

Once Hall decided to pursue a comedy career, he had no second thoughts.

“I just felt like, well, this is what I should be doing. And I also happened to start at a time when comedy was really starting to become a viable career choice. Suddenly, comedians (were) all over TV. And I just thought, ‘Oh, that’s what I want to do,’” Hall said.

“I think after learning how to be a street performer, I thought the obvious next step is to get indoors with a readymade crowd. So by the time I reached the clubs in New York, it was astounding to me that there was a crowd already there,” he continued.

One of Hall’s early breaks was his showcase for David Letterman’s morning television show on NBC in 1980. It was at the Improv, with some high profile company. In fact, Hall went on after Larry David.

“They were looking for writers primarily. So all of us thought, oh, what a great gig that would be. (Jerry) Seinfeld was there, Larry Miller, Paul Reiser. Everybody came out and did their tightest material, and they were great,” Hall recalled.

Everyone was so great that Hall decided to ditch his tight eight-minute showcase routine. Instead, he came out and badgered the audience into paying for pizza. He pretended he was a slightly unhinged Vietnam veteran who was now working as a pizza delivery man.

“And I decided, ‘I’m just going to walk through the audience and work my way to the back where I knew Letterman and his staff and writers and producer were and just kind of harangue Letterman into paying for pizza.’ It was crazy, but it worked. It really worked,” he said. “So they hired me as a writer. The next day, I went from going on to these late night gigs at the Improv and Catch a Rising Star in New York to walking into Rockefeller Center to my own desk overnight.”

“I felt like the reason I was hired was because we had shared sensibilities, Letterman and I,” Hall said.

“And basically anything I wrote for him, he made it better. I felt almost right away we were on the same wavelength. I just kind of knew how to write stuff for Letterman.”

Letterman’s morning show was canceled in October 1980.

While Hall was working on the HBO series, “Not Necessarily the News,” in the ’80s, he created “Sniglets” — words that should be in the dictionary but are not.

During the late ’90s, Hall invented a character named Otis Lee Crenshaw.

“That was my entrée into musical comedy. I came up with a character who doesn’t understand why nobody is recording his songs. But he’s been in prison most of his life, and a good number of songs are about being in prison. And he was very easy to channel because he was so many of my marginal relatives that I grew up with in the South, the ones coming out of the woods in North Carolina and Kentucky. And it was a character I knew inside and out,” Hall said.

When Hall toured Australia in 2009, he wrote and performed a song with his band at a funeral for a man that he’d never met.

“Some people came backstage, just kind of barged in and started saying, ‘You’re my granddad’s favorite comedian. He loved you.’ And then they said he just recently died, reversed his car off a supermarket parking lot in Adelaide. ‘And you’ve got to come to his funeral.’”

These people did not realize that Hall was playing a character. They believed that Otis was a real person. So Hall ended up performing a song about “this rotgut rum called Bundaberg, which is like jet fuel and alcohol.” And he went on to perform the song during his live shows.

-

The near death of comedy: How humor came back after 9/11

Here’s an old joke: “They made a Hindenburg-scented perfume. It’s called Eau De Humanitie.”

You probably thought that was funny, or maybe just a little funny. Anyway, the point is, it’s unlikely that you were offended by this joke that recalls a historical event that cost hundreds of lives. But when did it become acceptable to make “Hindenburg” jokes?

Spin forward in time 64 years to Sept. 11, 2001. When would it be appropriate for any comedy after that event? Especially humor that’s specifically about 9/11?

Wisconsin Public Radio’s “BETA“ talked with documentary director Julie Seabaugh about her film “Too Soon: Comedy After 9/11” to find out how we found our way back to humor after that tragic event.

“Remembering what it felt like to laugh again,” says Seabaugh, “was something that bonded us on this project. But it was a universal thing. That’s what the movie’s about. How can you laugh again in the face of tragedy?”

In New York City, everything shut down. The comedy clubs, Broadway, and television production all came to a grinding halt. But what were we to do?

Uncertainty, fear, and panic gripped the nation, and people everywhere found themselves floating in a cloud of grief with no direction. Then, finally, David Letterman found a way for laughter to return and begin the much-needed healing.

Seabaugh recalls, “Everybody watched (The Late Show with David Letterman), and it’s telling that it was a late-night comedy show. And it was also telling that Dan Rather was the first guest, which was recreating the events in a journalistic, somber, respectful way. And then they brought in comedy with Regis Philbin at the show’s end.”

After that, the way was clear for comedians to try and find a way to make sense of such tragedy. So on Sept. 27, 2001, The Onion devoted an entire issue to 9/11.

“When they decided to return to work after 9/11”, Seabaugh recalls, “with an issue that was all about 9/11 including amazing headlines like, ‘God Angrily Clarifies Do Not Kill Rule‘ or ‘Real Life Turns Into Bad Jerry Bruckheimer Film,’ and ‘Hijackers Surprised To Find Themselves In Hell.’ Every little piece of the paper, every story, every opinion piece, every chart, and graph were all about reacting to 9/11 with a mix of horror and sadness.”

The writers at The Onion felt they couldn’t ignore the sadness and grief they were dealing with in the aftermath of the 9/11 tragedy, but they had to be true to their mission of being a humorous publication. Amazingly, they pulled it off, and readers responded with calls and emails congratulating the writers for finding their way through and creating the most sensitive and funny issues they ever produced.

But finding the humor in the darkest situation was no easy task. A few weeks after 9/11, Comedy Central presented the New York Friars Club roast of Hugh Hefner. Gilbert Gottfried crossed a line with one of his jokes referencing 9/11. It didn’t go well.

“The crowd revolts,” says Seabaugh. “Someone shouted out, ‘Too soon.’ Everyone points to that being the moment of, oh yeah, we can cross a line. It can be too soon. This is when you learn if you don’t test the line, you don’t know where it is. So, Gilbert was the one who kind of sacrificed himself for the rest of standup comedy.”

From there, the comedy world found its sense of humor once again. Saturday Night Live honored New York’s first responders in their first show after 9/11 and then the usual comedy sketches. After that, the Daily Show reinvented itself as a political satire program and less of an entertainment spoof.

After making “Too Soon: Comedy After 9/11, Seabaugh came away with her own perspective on comedy and tragedy.

“It wasn’t so much you can’t make jokes about anything. It was the idea that you can’t tell people what they can and cannot laugh at. Different things appeal to different people. But the art form I find to be uniting. And when you’re sitting in that room in the back and see all these diverse people from all backgrounds and politics and religion, and they’re all laughing at the same thing in the same moments, there’s a little hope for humanity.”

In the film, comic genius Gilbert Gottfried sums it up this way: “Comedy and tragedy are roommates, and wherever tragedy is, comedy is standing behind its back, looking over its shoulder, sticking its tongue out and making faces.”

-

'Breaking the rules of linearity': Exploring the time-bending movies of Christopher Nolan

There are a lot of elements that make a film instantly recognizable as a Christopher Nolan film. There’s his austere, film noir style. There’s his preferred urban setting and a strong sense of realism. And, of course, there’s the lead character in a gray suit.

But one flourish seems to connect Nolan’s filmography more than any other.

“I think the distinct thing that makes a Nolanesque film is playing around with time,” UK film critic Ian Nathan said. “I think (Nolan’s) fascinated with the structure of films in terms of their linearity and breaking the rules of that.”

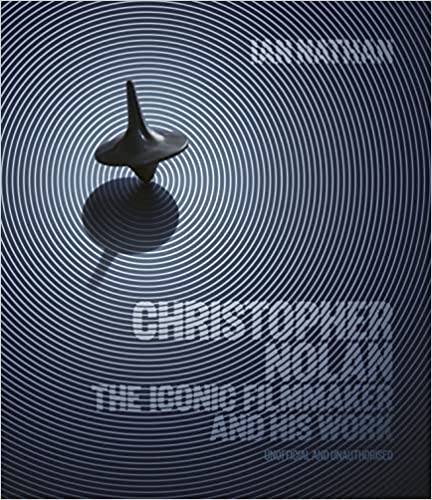

Nathan is the author of “Christopher Nolan: The Iconic Filmmaker and His Work,” which is the third in a series of books on iconic filmmakers like Ridley Scott and Guillermo del Toro. He tells Wisconsin Public Radio’s “BETA” that one doesn’t need to look much further than Nolan’s flag planting breakthrough, “Memento,” to get a sense of the director’s MO.

“Memento” was an indie and noir-ish thriller whose protagonist, Leonard (Guy Pearce), suffered from severe short-term memory loss, instantly forgetting nearly every encounter he had trying to solve his wife’s murder.

“The idea of a murder plot told through that character who can’t hold on to information, almost defeating the idea of a plot, fascinated Christopher Nolan,” Nathan said. “(Nolan) hits upon the inspired notion of, ‘If I tell this story backwards … then the audience has the same effect. The audience lose their memory.’”

According to Nathan, the result was a brilliant, controversial and rule-breaking film that sent the indie scene wild and entered Nolan into the mainstream.

Nolan’s next big wave would be revitalizing the Batman franchise for Warner Bros. with his Dark Knight trilogy. Nathan said that Batman’s lack of any superpowers appealed to Nolan’s filmmaking desires of realism.

“He could turn a comic book character, Batman and all the villains that are associated with him, into … sort of film noir style characters, and can make it very dark,” Nathan said.

The result was the critically and commercially acclaimed “Batman Begins” in 2005. Nolan again plays with time, floating in and out of flashbacks seamlessly to build the story of how orphan Bruce Wayne becomes the vigilante hero, delaying the actual first sighting of Batman until the film’s second half.

As Nathan writes, Nolan approached the film showing Batman primarily from the criminal’s perspective. This is a similar technique used by one of Nolan’s filmmaking heroes, Ridley Scott. Scott took the same approach to his titular alien, when he made his 1979 sci-fi horror classic, “Alien.”

Forgoing CGI as much as possible, Nolan shot on location and produced as many practical effects as he could. The result was a tactile film and reimagining of the comic book movie genre. This would be Nolan’s calling card throughout the trilogy.

“(Nolan) wanted to make them less fantasy, less huge,” Nathan said. “He said, ‘What happens if you put The Joker, the concept of the Joker into a real-world environment? What would he be? How would he function?’ And I thought, that’s really daring when you think about it.”

“The Dark Knight” — featuring Heath Ledger as the aforementioned Joker — would be the high-water mark of the trilogy and for comic book movies in general, and is still considered by many to be the best ever.

It would also reignite major studio’s desires to get back into the genre and has all but taken over mainstream filmmaking today.

Ironically, this renewed interest nearly blocked Nolan’s next few ventures. Studios were less likely to finance big budget original idea blockbusters in the wake of all the success of Marvel and other superhero movies — like “The Watchmen” — that followed “The Dark Knight” in 2008 and “The Dark Knight Rises” in 2012.

In 2010, Nolan finally did prevail in selling the studios on the puzzlebox, dream saga, “Inception,” perhaps by securing Leonardo DiCaprio to star. Nathan said that at its heart, “Inception” serves as an allegory for filmmaking itself.

“I think with Nolan, it’s much more explicit than maybe with other filmmakers,” Nathan said.

He points out that in the film — where an elite team of “extractors” who enter a shared dreaming space with a target to find out information or, in the case of the film, plant information — inhabit similar roles to a movie crew.

“Leonardo DiCaprio’s crack team are essentially a crew who build a narrative within the mind of their chosen target. And one of them is the architect, and there’s also the production designer. And one of them is the director,” Nathan said.

That DiCaprio’s look and wardrobe bear an uncanny resemblance to Nolan himself only serves to reinforce this allegorical read on the film.

Again, Nolan plays with the concepts of time. As the team goes deeper and multiple dream layers into the target’s subconscious, the dimensions of time warp.

Nolan would return to this concept in his 2014 sci-fi film “Interstellar,” which was a massively budgeted and researched epic about finding habitable planets to relocate our population before Earth’s imminent decay.

Nathan stated that even for heightened and fantastical story conceits, Nolan attempted to ground the picture in realism as much as he possibly could. Nolan hired noted astrophysicist Kip Thorne to serve as a consultant on the set.

“(Nolan) would show him the screenplay, and they would discuss the idea of traveling through wormholes and bending space and all these kinds of incredibly huge concepts because Nolan wanted to get it right, and he wanted to portray it accurately,” Nathan said.

“And again, you come back to the whole idea about time,” he continued. “That is the central Nolan fascination. So, you have that fantastic concept within physics of time running at different paces and in different locations.”

Nolan would be even more overt with time running at different paces in his World War II epic, “Dunkirk,” which followed three different story lines all covering three different time periods all concluding as the film does.

“So one is a guy in a Spitfire. One is a sort of team on a boat going over to rescue them. And one is the soldier on the beach,” explained Nathan. “Sea, air and land. These three different elements that he mixes up. And then, of course, he does this extraordinary idea of each one almost being in their own time signature, as it were, like a piece of music.”

Nolan — who split his citizenship between the U.K. and the U.S. growing up but spent his formative years in English schools — knew the history well. Part of that was because his grandfather had been in the war. What he found out and was fascinated by, according to Nathan, was that Dunkirk wasn’t about heroics as much as it was about simply survival.

“I think the more he conceptualized the idea of a Dunkirk film, the less it became a war film, and the more it became a film about something much more primal,” Nathan said, “which was our instinct to survive. What are we willing to do under these circumstances to survive?”

Nolan will return to the period with his forthcoming film, “Oppenheimer,” starring Nolan stalwart Cillian Murphy. Nathan states that this should present the imaginative director with a new challenge as he’s never done a biopic before.

“This has been an itch that needed scratching,” Nathan said. “What kind of film it will be, I’m so fascinated to know. What will he do with the biopic? I’m sure it’ll be revolutionary when we come to see it.”

There’s little reason to doubt that sentiment.

Episode Credits

- Doug Gordon Host

- Adam Friedrich Producer

- Steve Gotcher Producer

- Tyler Ditter Producer

- Steve Gotcher Technical Director

- Rich Hall Guest

- Julie Seabaugh Guest

- Ian Nathan Guest

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.