Wisconsin mental health advocates are calling for more funding and investment in access to care amid fast-growing demand for services.

Leaders spoke at a virtual Wisconsin Health News event this week to address community needs as the state sees what Gov. Tony Evers described as a “quiet, burgeoning” mental health crisis.

“We are very concerned about the crisis service system right now. I like to say we can either pay for it now, or we can pay for it later,” said Mary Kay Battaglia, executive director of NAMI Wisconsin, an affiliate of the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

She said a shortage of providers means people are having a hard time finding care when they need it.

“The number one thing is the workforce. We’re having moms call our office to say they’ve got an appointment in nine months for their son who just had a suicidal attempt at a hospital,” she said.

Wisconsin’s suicide and crisis hotline call volume soared since it adopted a shorter 988 number. In January, the line received 6,030 calls, compared to 4,074 in January 2022.

The state Department of Health Services reported the suicide rate in Wisconsin outpaces the average of neighboring states. The suicide rate was higher every year since 2005, save for 2012, according to a recent Mental Health and Substance Abuse Needs Assessment.

The Wisconsin Office of Children’s Mental Health reported earlier this year that more than half of high school students in the state experience anxiety. The number of students reporting feeling sad or hopeless almost every day has risen by 10 percent over the last decade.

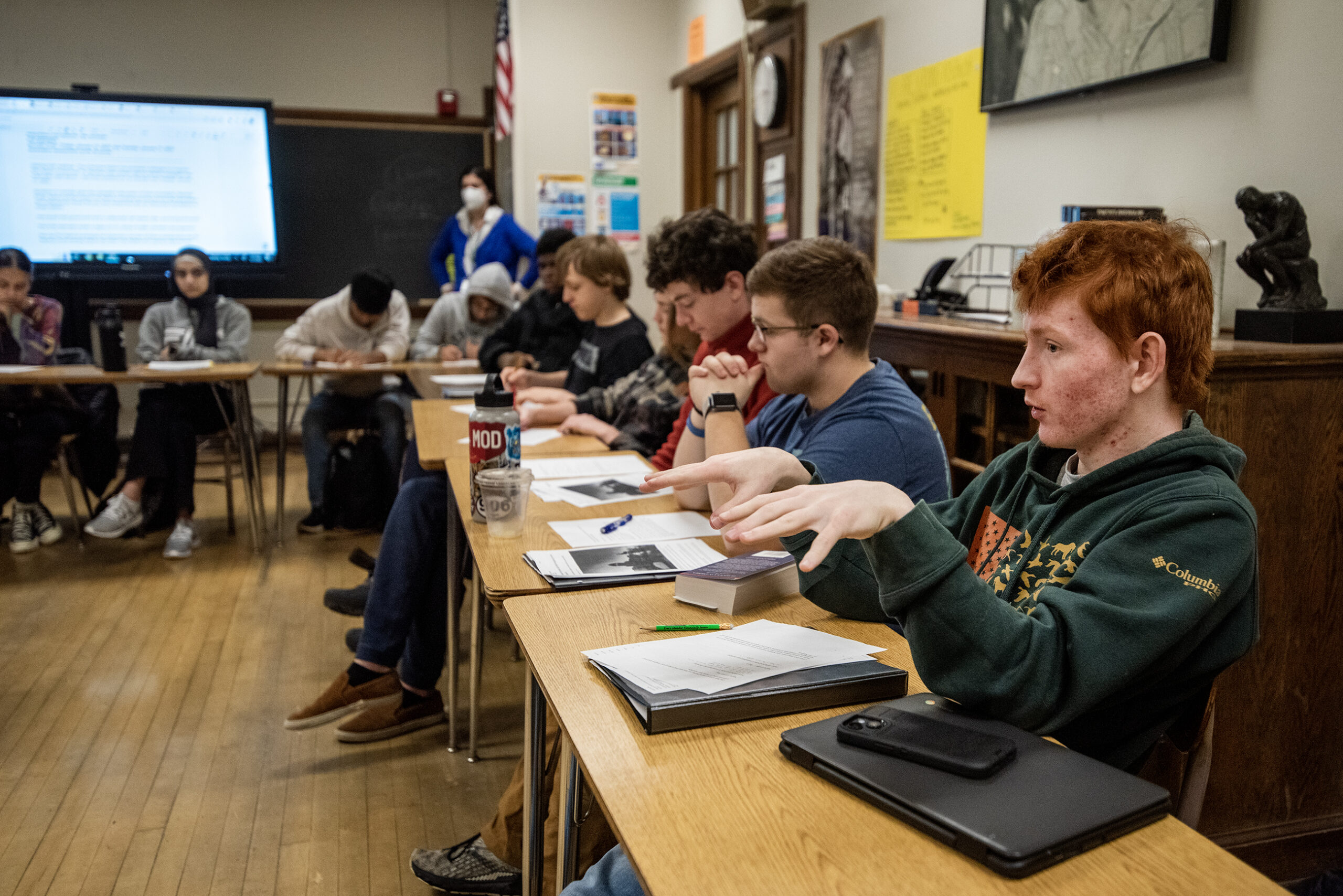

Linda Hall, director of the state Office of Children’s Mental Health, said educators are sounding the alarm as they look to help kids surmount difficult mental health challenges.

“We hear school staff and teachers saying kids are coming to school with such severe trauma and issues that they’re dealing with that we need help, we need space to address mental health and work with them,” Hall said. “And we need the training to be able to do that.”

Hall said one solution she hopes to see is health plans that pay for qualified treatment trainees — people with a master’s degree and some experience but without licensure yet.

Battaglia also would like to see the state focus on “earn-while-you-learn” career ladders to increase the number of providers and expedite the licensure process for social workers.

In Wisconsin, 440 people are served by one mental health provider, according to a County Health Rankings & Roadmaps report in 2022. Nationally, that ratio shrinks to 350 people to one mental health provider.

Amy Herbst, vice president of mental and behavioral health at Children’s Wisconsin, agreed licensure can be a barrier.

“There are a variety of reasons why there have been licensing issues. But the bottom line is that we have lost applicants, and we can’t afford for that to happen,” she said.

Herbst said the Wisconsin Hospital Association worked with the Legislature and Gov. Evers to pass legislation two years ago allowing health care providers from outside the state to apply for temporary licensure and start practicing in Wisconsin.

“That allowed providers to be able to practice, which then provided access to mental healthcare to our kids. So that was a solution to the licensure problem,” she said.

In an interview with Wisconsin Public Radio, Tony Thrasher, president of the Wisconsin Psychiatric Association, said the state should go one step further by making those licenses permanent.

Thrasher said there’s a national physician shortage, but it’s worse in psychiatry.

“It’s affecting mostly every state. So I don’t think Wisconsin is any different in that. But I do think Wisconsin is on the wrong half of that equation,” he said. “We have more psychiatry vacancies than most other states.”

Even before the pandemic, 55 of the 72 counties in Wisconsin had “significant shortages” in psychiatrists, according to a report from the UW Population Health Institute in 2019.

Thrasher said psychiatry is the oldest medical specialty, with an average provider age of 55 to 56. He said early retirement trends, physician burnout, and dissatisfaction of physicians with health care and health care systems are leading more psychiatrists to leave the profession.

“Unfortunately, what we’re seeing now is probably just the tip of the iceberg. There’s probably gonna be deeper shortages before it gets better,” he said.

Rep. Paul Tittl, R-Manitowoc, is chair of the Assembly Committee on Mental Health and Substance Abuse Prevention. He said he supports a bill that would provide up to a $200,000 income tax deduction for psychiatrists who serve in medically underserved areas.

“We always run into a certain amount of resistance because people don’t want to spend the money to do it,” Tittl said.

Hall of the Office of Children’s Mental Health said some possible solutions are to focus on collaboration between schools and community mental health providers and to help kids become more mental health literate.

She said the money that has been invested in school mental health previously has made a difference, “but we need to provide sustainable, ongoing funding.”

The governor has proposed spending $500 million over the next two fiscal years in mental health services, with more than $270 million making the “Get Kids Ahead” mental health initiative a permanent program. That would include $18 million a year to reimburse schools for hiring school counselors, psychologists and nurses, along with $580,000 a year for training.

Herbst of Children’s Wisconsin called that funding critical.

“We need to treat mental health like health,” she said.

If you or someone you know is considering suicide, call the suicide prevention lifeline at 988 or text “Hopeline” to 741741.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.