For a lot of people, the idea of a female spy resembles something akin to Mata Hari or La Femme Nikita — a beautiful seductress who uses her sexuality to acquire state secrets and beguile men.

It’s an image popular culture has reinforced for decades in James Bond films and in shows like “Covert Affairs” or “Alias.” But it turns out that actual female spies are nothing like their on-screen counterparts.

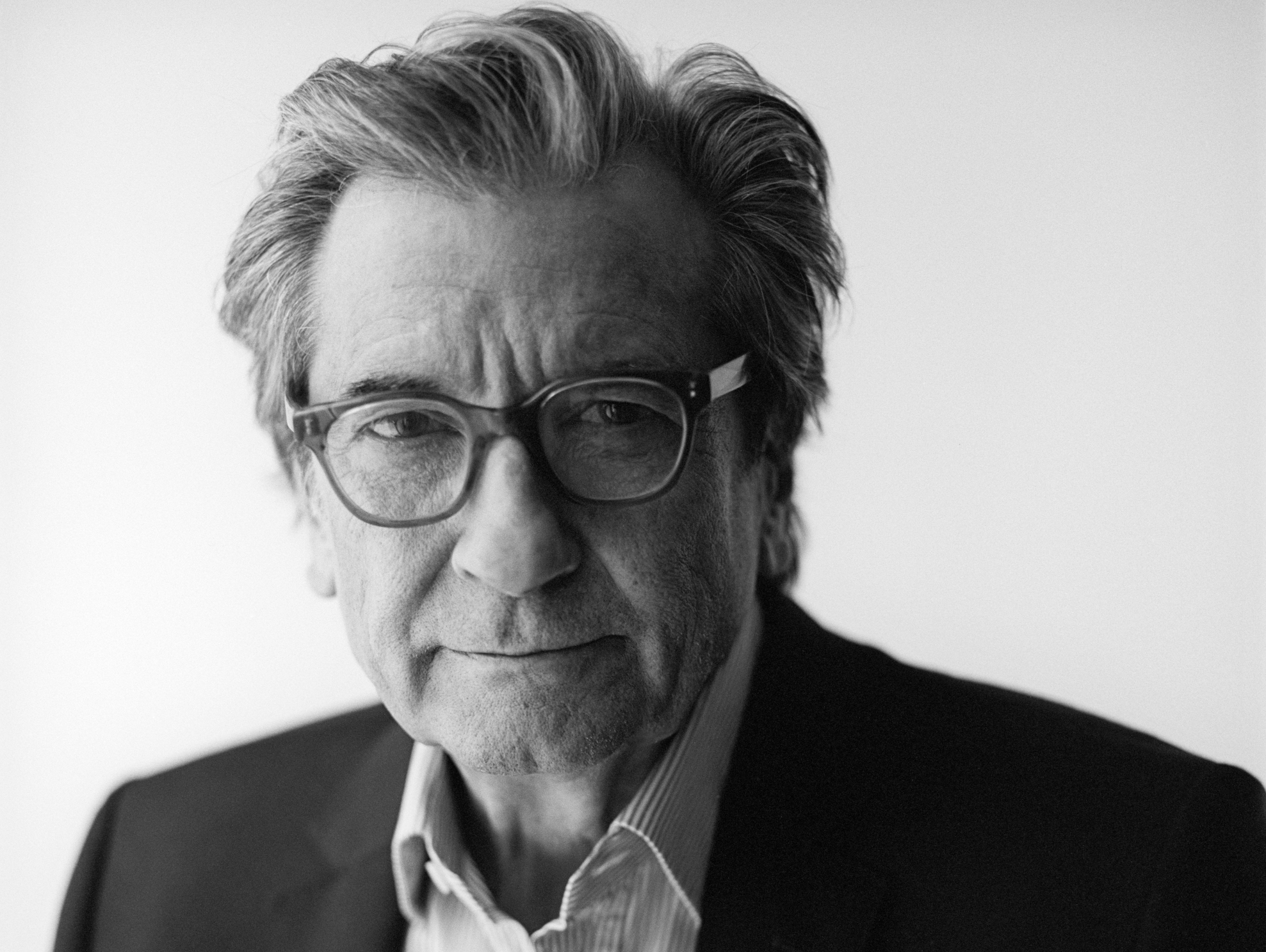

According to former CIA operative Valerie Plame Wilson, real spy work is far more mundane, comprised mostly of research and other tasks that require time and patience. Wilson spent years recruiting and developing a network of intelligence agents before she was publicly outed by senior members of the second Bush administration in 2003.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

And although she no longer jetsets around the world for the CIA, she hasn’t left the spy game entirely. Last year, she released her second spy-thriller novel, “Burned,” written in part to combat popular myths about female spies.

She spoke about her book, her experience and the media portrayals of spy work with “To The Best Of Our Knowledge” producer and host Anne Strainchamps:

Anne Strainchamps: In many popular depictions of female spies, they’re seen seducing somebody for intelligence. Does that really happen?

Valerie Plame Wilson: So eye-rolling. The U.S. and most other Western intelligence services do not use the so-called “honeypot” (strategy of) seduction. It doesn’t work.

It doesn’t?

No, it really doesn’t work because there’s too many emotions involved.

What can you tell us about what you actually did in the field?

What I can tell you is that my expertise began to develop and coalesce around counter-nuclear proliferation. And what that means is essentially making sure the bad guys — whether they’re terrorists or rogue nation states — do not get a nuclear capability. And I loved my work. I loved my career. It felt — not all the time — but it felt many times like it was meaningful. That you were doing something worthwhile.

One of the things that’s always struck me as just particularly difficult for case workers is getting attached to your recruits. Would you ever like them or feel sympathy for them?

Oh absolutely, they’re human beings after all. In many cases, you develop a real friendship, a real relationship with them. And regardless if they’re nice people or not, you have made a pact with them to protect them because sometimes the consequences are pretty dire.

So when your identity was leaked to the press and that blew your cover and ended your career. Did it also put you in danger?

Yes, my family as well. Because there are so many disturbed people in the world. All of a sudden, I was everywhere. The media maelstrom was incredible and went on for several years. Until we moved to New Mexico where we are now, we were living in Washington, D.C., and our front door was a few steps from the street. I felt very exposed, to say the least.

And what about that whole network of recruits you’d cultivated. When you were blown, some of them must have been endangered as well?

Yeah, and to this day, that causes me great sorrow. I was deeply disturbed by those that we promised to and could not help. Many of those scientists were killed or they disappeared or they went to Iran. I just lost my career, but there were a lot of people whose lives and families were in jeopardy. I know what happened to some, I don’t know what happened to others. It’s very painful.

How dangerous was it? Did you ever feel real physical danger during your CIA career?

That’s what my mother always wants to know. And here’s the other huge fallacy that you see in how operations are depicted generally. (People think) it’s a lone wolf thing and it’s not. There is an enormous team behind you. If I was meeting with a terror suspect, I had surveillance on that meeting, and it was generally in a quiet but public space. You’re not this lone wolf out there trying to figure it out all on your own.

Were there times when you’d be meeting and looking right into the eyes of somebody and think, “This guy would kill me if he could.”

Yeah, I can think of a couple instances, but the training that goes into operations officers is incredible. It takes years and hundreds of thousands of dollars. And hopefully you have something to offer to this person so that they are listening very carefully to what you have to say.

Going back to those recent TV shows about spies, lately I’ve noticed that a lot of them are mothers. But you’ve done that too — been a mother and a spy. Was it difficult?

Yes it is, but it’s hard no matter what. I was fortunate in that when my twins were born my parents were close by so they helped out a lot when I had to travel. Sometimes of course, I’d have to take my kids into the office, and I’d toss some animal crackers and some cheap little toy, just to give me 20 minutes to write something or make phone calls. I realize that the career is a little bit odd, but I don’t want to overplay that because millions of working mothers are trying to figure out balance. You’re such trying to survive and get through it.

Yeah, it’s just that most of us working mothers don’t go from packing lunch to chasing down rogue nuclear weapons.

I see your point, but I didn’t see it as weird. I loved what I did. I was really proud to serve my country and it was simply part of it. My CIA identity was betrayed by senior officials in the Bush Administration in 2003. My children were very young and I didn’t have to deal with the big question which many of my former colleagues did, which is at what point do you tell your children what you really do.

How do most agents tell their children what they really do?

It varies from case to case. For the most part, most of the children sort of already know. And it comes as a relief to them because it’s like, “Oh, dad is not having an affair. There’s a reason he’s out more nights than not.”

Why do you think we love spy stories? Is there something about our attraction to secrecy or to the idea that someone’s living a double life?

We’re living in an age of oversharing. Way too much is out there on social media, and even for my teenagers now, the concept that someone would withhold information or live a double life is really hard to imagine. The other reason is that since 2001 we’ve heard and read so much more about the CIA than we ever had before, for good and bad. We’re constantly being told about national security threats and so forth, so it’s very much a part of our culture now.