A conservative group is trying to get a jump on the next round of redistricting, proposing a rule change Wednesday that would require that any lawsuit over political maps run through the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

It’s just the first of what will likely be many legal maneuvers over redistricting, the process through which legislative district lines get drawn every decade after the U.S Census.

The request by the Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty (WILL) is a potentially significant step because whichever court hears the next redistricting lawsuit could have extensive say over the next political map, which will lay the groundwork for elections beginning in 2022 and running through 2030.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

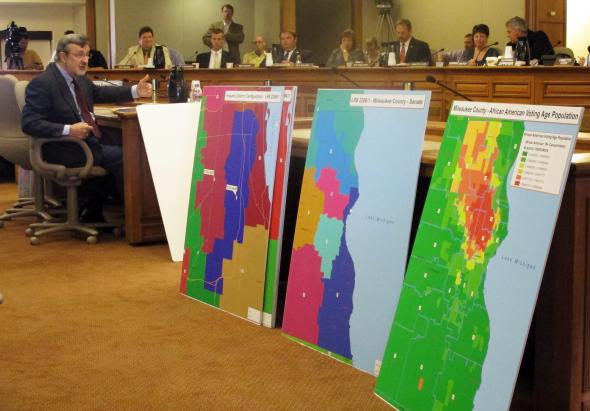

Republicans controlled both the Legislature and the governor’s office during the last redistricting process in 2011, which let them draw district lines that gave their candidates a political edge over the past decade.

The situation is likely to be different this time around because Wisconsin is under divided government, with Republicans holding huge majorities in the Legislature and Democratic Gov. Tony Evers expected to veto any GOP redistricting plan that arrives on his desk.

“Unless the Democrats take over the Legislature, we would not expect the Democratic governor and the Republican Legislature to be able to agree on maps because we know that they never do,” said Rick Esenberg, president and general counsel for WILL. “Under those circumstances it’s going to be necessary for the court to draw the maps.”

The rules petition by WILL is based on the idea that redistricting is fundamentally a responsibility of state government, but it also reflects the political reality that conservatives hold a majority on the Wisconsin Supreme Court. Unless one of the justices leaves the bench before the end of their term, that majority will likely remain in place during the next round of redistricting.

Under WILL’s proposal, any redistricting lawsuit would be handled as an “original action” before the Wisconsin Supreme Court, meaning it would bypass lower courts. The governor and Legislature could present their own redistricting plans and outside groups could also intervene.

“The court will have the ability either to choose among those maps or to generate a map of its own,” Esenberg said.

Federal courts have played a much bigger role in Wisconsin’s most recent redistricting battles. In 2012, a three judge federal panel ordered parts of two Milwaukee Assembly districts redrawn. In 2016, a federal panel ruled the entire GOP redistricting plan unconstitutional before the U.S. Supreme Court remanded the case.

Should WILL prevail in its rule petition ahead of the next redistricting process, Esenberg said other plaintiffs could still file federal lawsuits, but they’d need to be more focused.

“Nothing would prevent somebody from asserting a federal claim, but I think a federal court under those circumstances is likely to say, ‘Look, we’re not going to interfere with the state court process,’” Esenberg said.

Esenberg said he hoped the court would consider the rules petition in the fall. He said he did not expect the court to consider it before conservative Justice Daniel Kelly’s term ends and Justice-elect Jill Karofsky’s term begins, which will trim the conservative majority from 5-2 to 4-3.

Evers has also taken a preliminary step to prepare for the next round of redistricting, calling for the creation of a “People’s Maps Commission” earlier this year.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.