Snowbanks blocked Colleen Rooney’s view of the water when she and her husband first arrived at their new lakeside home in rural Vilas County last month.

“I actually had to hire someone to come take a skid loader and get the snow away from the garage so we could unload the truck,” Rooney said.

The mounds of snow stood in stark contrast to the hot, arid desert they had left behind in Las Vegas. She and her husband Jim had lived there since 2000, but Rooney said she was done with 115-degree heat.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“You just didn’t go anywhere when it was 115 degrees outside,” she said. “Just to walk from your car to a grocery store across that blacktop was brutal, so you’d go shopping after the sun went down.”

At night, the 67-year-old would jump into an inflatable hot tub filled with ice cold water just to cool off. Jim, 68, said temperatures had become more brutal.

“It’s getting to where they’re starting to get concerned about having enough water,” he said.

Danielle Kaeding/WPR

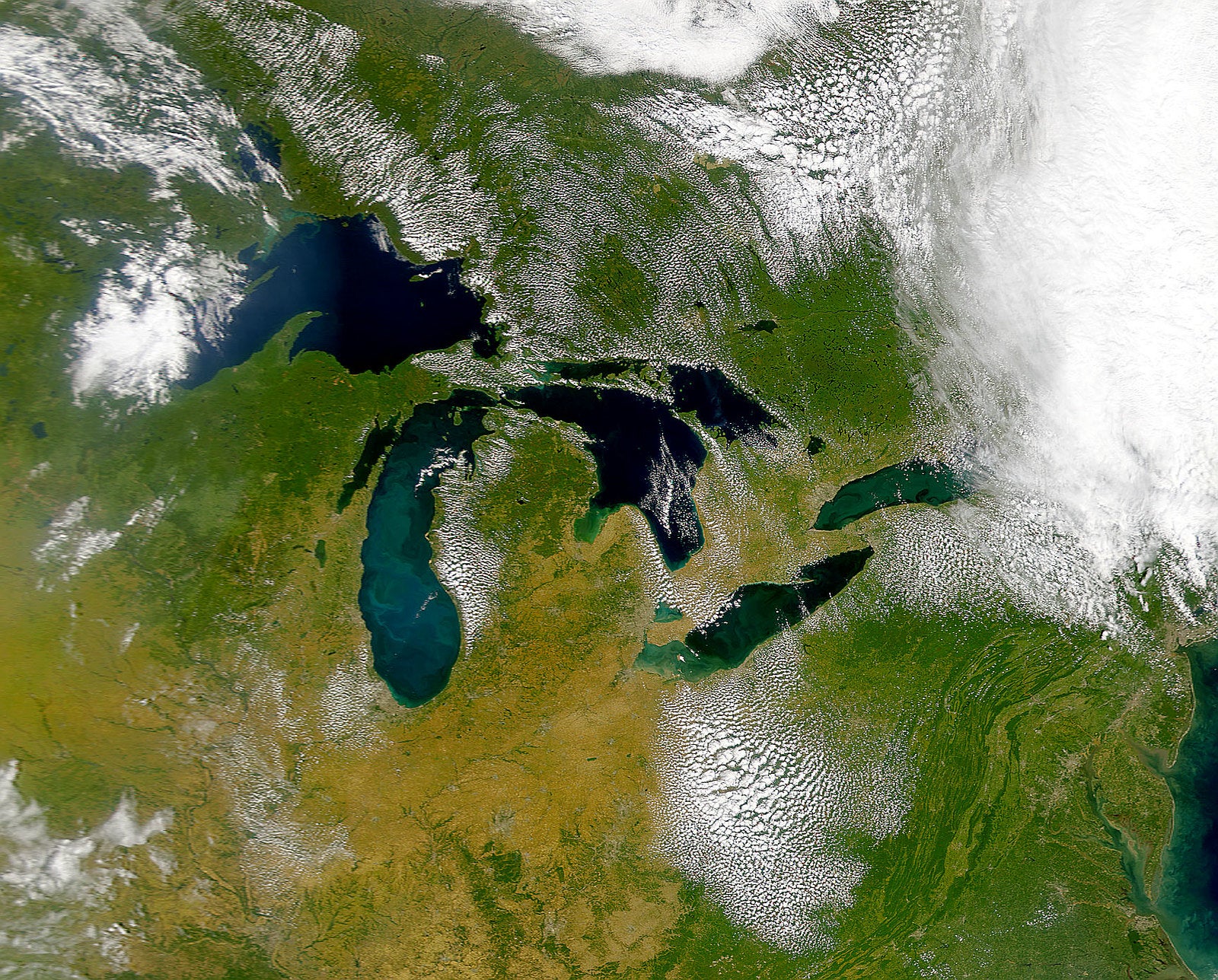

The Rooneys do not consider themselves climate refugees, but the rising temperatures and scarce water resources of the Southwest were a big part of the reason they moved to Wisconsin. Climate migration experts say the Great Lakes region will face lower climate risks than other parts of the nation. But that doesn’t mean Wisconsin and the Upper Midwest are immune to the effects of climate change, which is already affecting weather patterns here and across the globe.

It’s impossible to know exactly how rising temperatures and changing climate will affect where people choose to live or what it will mean for Wisconsin. But experts say there will be effects – and the experiences of people like the Rooneys are one sign that they are already being felt.

Globally, scientists predict up to 143 million people may be forced from their homes as climate change drives temperatures and sea levels higher. Those changes could be catastrophic for some island nations, and even coastal cities. And in the U.S., conditions like the brutal drought in the West that caused Lake Powell, near where the Rooneys used to live, to drop more than 150 feet over the last two decades could become more common.

In Wisconsin, the changing climate will mean more frequent and longer heatwaves, as well as more frequent and intense storms, including destructive storms that lead to flooding or downed trees. But it’s also possible that a state with a relatively cool climate and plentiful water resources could be protected from some of the changing climate’s worst effects.

Climate disasters, rising temperatures are already affecting migration

The Western drought and Hurricane Ian, which hit Florida and caused nearly $113 billion in damage, were among the nation’s most costly climate-induced disasters last year. A survey last August commissioned by the real estate company Redfin found around 62 percent of people who plan to buy or sell a home this year are reluctant to move to a place at risk of natural disasters, extreme heat or rising sea levels. That’s even as more people are moving to disaster-prone areas like Florida in recent years.

As some people seek to escape climate risks, several Great Lakes cities have sought to market their communities as a potential refuge, including Duluth, Minnesota, which borders Superior in northern Wisconsin.

Jesse Keenan, an associate professor of sustainable real estate at Tulane University, coined the slogan “climate-proof Duluth” in 2019 as part of a design and planning research project commissioned by the University of Minnesota-Duluth. Keenan, who lectured at Harvard at the time, said the term was meant to be funny while marketing the city as one that faces relatively lower risks from climate change.

“It was not a literal idea in the sense that anybody can be climate-proof because no one is immune from the impacts of climate change,” Keenan said.

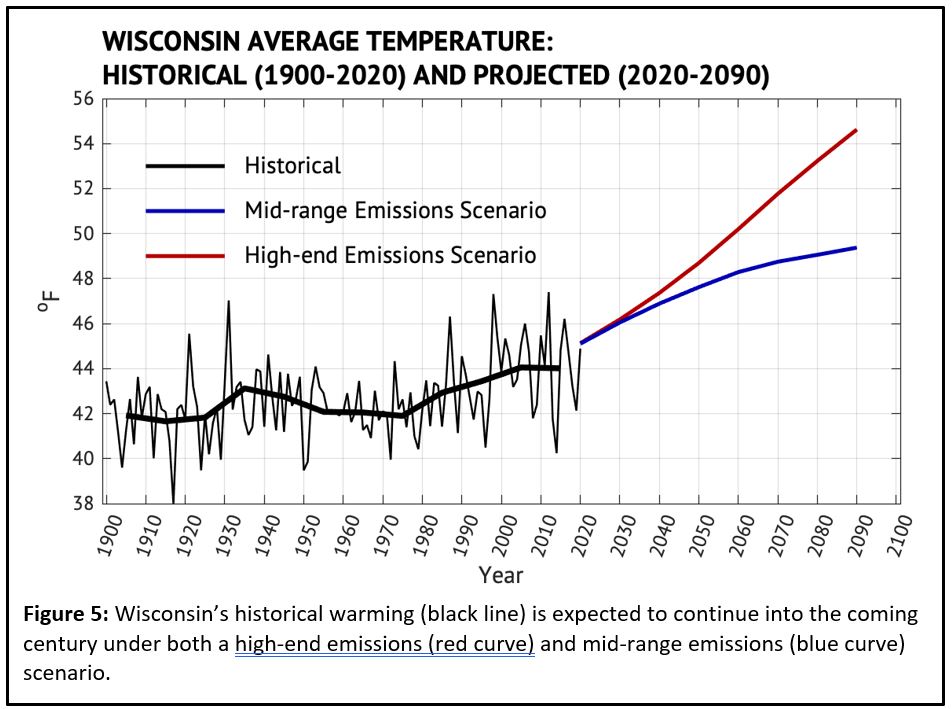

Temperatures in Wisconsin are expected to climb between 2 and 8 degrees Fahrenheit by mid-century. That’s according to the latest report from the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts.

“We talk about (how) Wisconsin may be relatively better than other parts of the country, but ‘relatively’ is the key term, because we have our own challenges,” said Steve Vavrus, the initiative’s co-director and a climate scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

While the Southwest struggles with access to water, Wisconsin has seen too much in recent years. The last decade was the state’s wettest on record since record-keeping began in the 1890s. More frequent, intense rains have prompted severe floods that caused $2.3 billion worth of damage in 2019 alone, according to federal data.

Yet, some argue global warming will benefit Wisconsin, including Wisconsin’s Republican U.S. Sen. Ron Johnson, who has called climate change “bull—-.”

In a recent Senate budget committee hearing, Johnson questioned one of the authors of a study published last year in the Quarterly Journal of Economics about the projected effects of rising temperatures on the risks of excess deaths.

“In my own state, your study shows that we’d have a reduction in mortality of between 54 and 56 people per, I guess it’s 100,000,” Johnson said. “Why wouldn’t we take comfort in that?”

Michael Greenstone, one of the study’s authors and director of the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago, explained the effects of climate change will be “very unequal.” While the rate of deaths due to cold is projected to drop in Wisconsin, those rates will climb due to heat across the nation’s southern and western states.

“If you look more carefully at that, there are large swatches of the country where the damages will be much larger,” Greenstone said during the hearing.

As rising temperatures make some areas increasingly uninhabitable, a group has formed to examine climate migration to Wisconsin.

“We kept hearing people are moving because of climate, sea level rise, big hurricanes, wildfires, so should Wisconsin be worried about this?” said Anna Haines, a professor and director of the Wisconsin Center for Environmental Education at UW-Stevens Point.

Haines, who co-chairs the initiative’s community sustainability group, said they formed a committee that will consider the positive and the disruptive effects of climate migration and identify any best practices for communities that may see a boost in their population. She said a big question is whether Wisconsin may see more people moving in than moving out due to climate change.

If more people move because of climate, is Wisconsin ready?

More people moved into Wisconsin than left through June last year, according to most recent estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau. The state saw a net gain of 15,831 residents with more than 7,657 people moving from other states across the country.

But evidence about climate migrants to Wisconsin is lacking.

Determining who is a climate migrant and what is considered evidence of climate migration is also challenging to suss out from federal data, according to Katherine Curtis, a professor of community and environmental sociology at UW-Madison.

“People tend to move for many reasons, and sometimes intersecting reasons,” Curtis said. “The climate or environmental conditions are certainly reasons for some people, but possibly only indirectly, as opposed to like the first and foremost driving motivator.”

For Colleen Rooney, her emotional ties to northern Wisconsin where her family vacationed and lived when she was a kid played a large role in their decision to move to Vilas County.

Danielle Kaeding/WPR

But Curtis and other migration experts note people tend to move short distances. That is true for people moving to Vilas County and the rest of Wisconsin.

Most recent federal data on state-to-state migration from 2019 shows the vast majority of people who moved to Wisconsin come from neighboring states like Illinois, Minnesota, and Michigan. Outside the region, estimates show the state gained the most new residents within the U.S. from states like California, Florida, and Texas.

Curtis said the data suggests that climate migration could be happening, but stronger evidence is needed.

Migration experts including Matt Hauer, assistant professor of sociology at Florida State University, say it’s also less clear when people may decide to leave their community because of slower changes in climate over time.

“It’s really easy to imagine a migration occurring when a town burns down, for instance, or gets flattened by a tornado or something similar,” Hauer said. “But it’s much harder to see a relationship with something that’s much more slow-moving, like when people decide my road is flooded 10 times a month.”

If people decide they’ve had enough, Wisconsin may face challenges accepting any climate refugees/migrants. The state needs to build at least 140,000 housing units by the end of the decade just to meet current demand, according to one recent report. If the state hopes to add to its workforce, then that number rises to 227,000 units.

In northern Wisconsin, Haines said she and another committee member have been interviewing realtors in the Ashland and Bayfield area to better understand what’s happening in the market.

“As they are selling property to people, there are people who are buying property, sometimes sight unseen, sometimes with cash,” Haines said. “So it’s often their second or third home. Sometimes it’s to rent, and they’re kind of saving it in reserve in case they leave California or wherever.”

The lack of housing supply combined with potential climate migration could exacerbate existing challenges or inequality among some communities. In Ashland and Bayfield counties, more than half of roughly 2,000 residents surveyed in 2021 said housing is already lacking for renters and people with lower incomes, and they couldn’t afford a monthly rent or mortgage of more than $800.

“We know that those who have the most means are those who are most likely to move, and they’re also the most likely to adapt in place,” Hauer said. “And we know that those with the least means are the least likely to move, and the least likely to adapt.”

The uncertainty over how people will respond to climate hazards and where they will move makes it difficult to gauge how communities may be affected. Even so, climate migration experts say they may want to conduct long-range strategic planning and think about the availability of jobs and infrastructure to accommodate climate migrants.

“Make the investments that you are going to make to improve housing, improve the affordability of housing, improve your school system, parks, et cetera,” Keenan said. “Make the investments that you are going to make, that you should be making, in the interests of the communities that already live there.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story said the University of Minnesota-Duluth had commissioned an economic development and marketing package. The story has been corrected to reflect that the university commissioned a design and research planning project.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.